Connecticut spends roughly $450 million out of the Special Transportation Fund every year to subsidize bus and rail operations, with most of its rail line costs exceeding other rail lines in the United States, according to a state efficiency report by the Boston Consulting Group.

Ridership on both bus and rail lines have plummeted during the COVID-19 pandemic as workplaces closed and people began to work from home and avoid crowded public spaces, leading to even less fare revenue to help pay costs.

With the STF facing potential insolvency in the next few years, BCG suggests opening bus and rail operations to competitive bidding and reducing or even eliminating some rail lines.

“Connecticut should evaluate opportunities to reduce bus and rail spending,” the consultants wrote. “It can do this by introducing further competition for the State’s bus and rail contracts.”

However, the state faces a substantial hurdle in opening its bus contracts to other bidders.

According to the report, the Connecticut Department of Transportation has faced litigation for over a decade trying to introduce competition for Connecticut’s private bus operators.

“The central issue is that a handful of private bus operators holding government-issued certificates to operate bus service over fixed routes,” the report says. “The certificate holders believe that these certificates – issued starting in the 1970s by now-defunct agencies – represent lifetime rights and the State has been unable to take measures to save taxpayer money and improve bus service operations.”

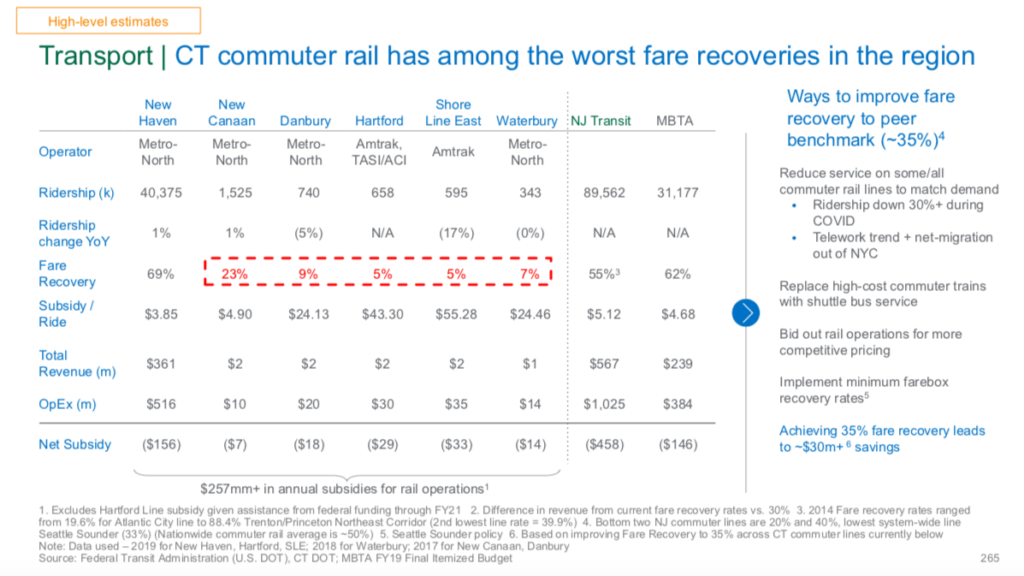

The report, however, found that Connecticut’s rail system is “substantially more expensive” than bus operations, with annual subsidies totaling $257 million. Although the state collects more fare revenue from train riders, the fares are nowhere near enough to pay for operations.

“Even prior to the pandemic, fare recovery rates for Connecticut were generally lower than in other States, including Connecticut’s neighbors,” the report says. “While the New Haven Line is among the country’s best performers in farebox recovery rates; lines such as Shore Line East, Waterbury and Danbury are among the nation’s lowest performers by this same metric.”

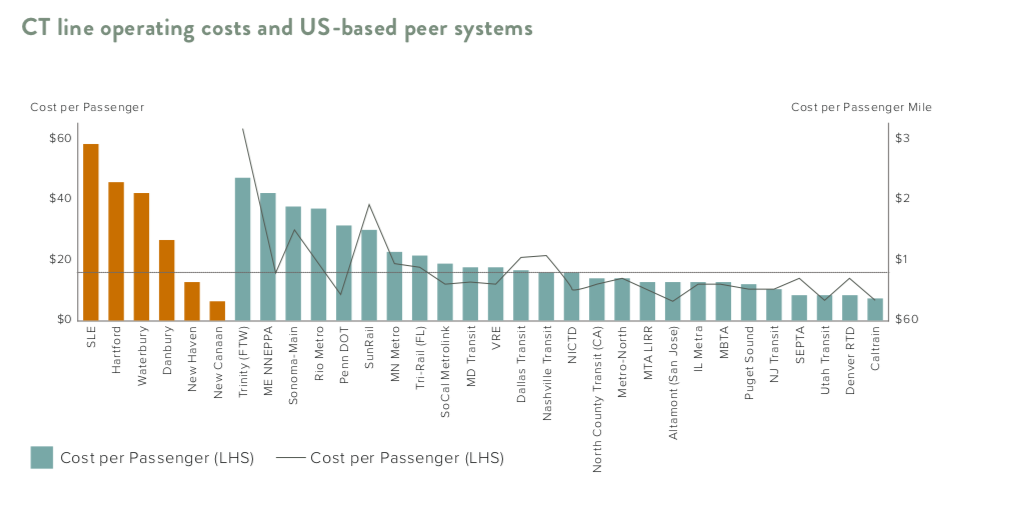

Only two rail lines – the New Haven Line and the New Canaan Line – have operating costs below the national median for peer states.

The worst performing rail line by far is Shore Line East where the state is paying subsidies totaling $55.28 per passenger, followed the Hartford Line which costs $43.30 per rider.

The Hartford Line, which connects New Haven to Springfield, Massachusetts was recently completed in 2018 at a cost of $570 million. According to a report footnote, the Hartford Line subsidies were not included in the $257 million subsidy figure because of assistance received from the federal government through fiscal year 2021.

The Boston Consulting Group recommended replacing high-cost commuter trains with shuttle buses.

The report also recommends reducing service on rail lines, particularly in light of the pandemic drop-off in ridership, implementing a 35 percent fare recovery benchmark and opening rail operations up for competitive bidding.

Connecticut’s fare recovery averaged 19.6 percent but ranged from a high of 69 percent on the New Haven Line to a low of 5 percent for the Shore Line East and Hartford Lines.

BCG estimates that Connecticut could save $30 million if it established a base 35 percent fare recovery rate and an additional $10 to $20 million in savings through using a competitive bidding process.

Connecticut has already reduced service on the Shore Line East and Hartford Line due to the massive drop-off of riders due to the pandemic.

Gov. Ned Lamont factored the service reductions into his budget proposal, positing savings of $34.9 million per year from reduced service on the New Haven Line, which he extends to the out-years. It also posits a one-time savings of $5 million from reduced service on Shore Line East and $3 million for consolidating Express bus routes.

However, the governor also included an expansion of rail service on the Waterbury Line.

Lamont is hoping to also bolster Connecticut’s public transportation system through the Transportation and Climate Initiative — a multi-state cap and invest system that requires gasoline wholesalers to purchase emission credits at auction.

The revenue from the TCI would be leveraged on the expense side of public transportation, with savings between $24 and $69 million. However, since Lamont’s budget proposal the TCI legislation was altered to dedicate more of the money toward climate justice and equity in cities

The governor also hopes to boost the Special Transportation Fund with a weight-mileage tax for trucks, assuming upwards of $100 million in revenue by 2026.

“Transportation agencies across the country are trending toward using competitive Requests for Proposals to introduce competition and realize expense savings,” the report said. “Based on benchmark analysis, the State could potentially realize annual savings of at least $10m-$20m by introducing competitive bidding on operations of a subset of lines.”

dean bonanno

April 16, 2021 @ 8:12 am

Dear Mr. Fitch,

Excellent article on the financial status of the state’s rail and bus service. I would only add that the fare recovery figures are bolstered by the mandatory “UPass” purchase fee tacked on to undergraduate fees in many colleges across the state. while redeemed for transportation to/fro college by some students, it has been a non-used subsidy by most. although, it has been used by central connecticut students for safe trips to the pre-pandemic weekend bar scene in hartford, via fasttrack, to the bane of new britain proprietors.

Tom Aparo

April 19, 2021 @ 5:35 pm

I Would like to point out that the ctrail hartford line service was actually awarded off a competitive bidding process,

Ben

June 2, 2021 @ 8:58 pm

This is a joke, right? Reduce and kill public TRANSPORTATION? How about we expand it so that people can access it better and ACTUALLY use it from one destination to their final destination. This report is a joke!