Sabrina Romansky contributed to this article

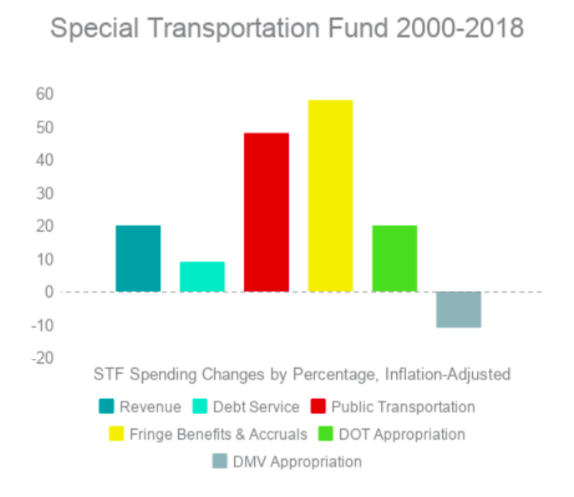

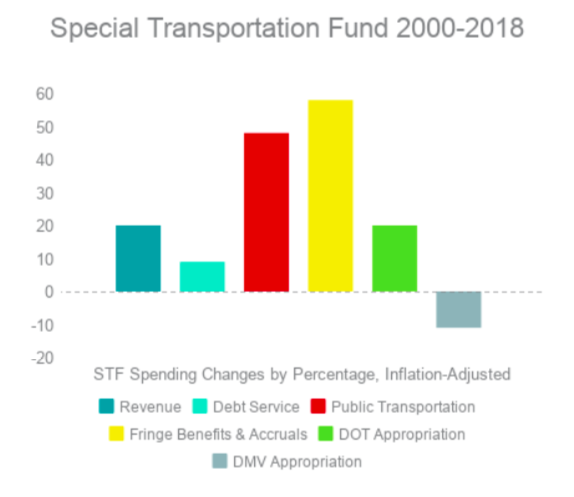

Connecticut’s transportation funding problems have been blamed on increasing debt costs and flat or declining revenue, but a look at the history of transportation spending in Connecticut shows that, when adjusted for inflation, the biggest cost increases have been for public transportation and fringe benefits for employees.

Connecticut’s transportation funding problems have caused a renewed push to install electronic tolls on Connecticut’s highways.

Gov. Dannel Malloy issued an executive order for a $10 million bond to study the implementation of electronic tolls on Connecticut’s highways, saying in his press release that, “developing a new funding method is due to the ongoing destabilization of the Special Transportation Fund.”

The “destabilization” of the STF was blamed on spiking debt costs and less gasoline tax revenue in a December 2017 report released by the Office of Policy and Management. But a look at the history of Connecticut’s transportation revenue and spending between 2000 and 2018 tells a slightly different story.

When adjusted for inflation, revenue to the STF has increased by 20 percent since 2000, while debt costs are only up 9 percent.

Meanwhile public transportation spending has increased 48 percent and fringe benefit costs increased 58 percent, according to figures compiled from Connecticut’s budget book.

The STF is funded primarily through the gasoline tax and a tax on oil companies, along with a number of motor vehicle taxes and, more recently, a percentage of the state’s sales tax revenue.

This year, the STF will spend $614.6 million paying for debt, which is 40 percent of total revenue.

However, in 2000 the state’s debt payments were $385.9 million which equaled 45 percent of revenue. Adjusted for inflation, debt service spending has increased $50 million since 2000.

Spending for public transportation grew $177.3 million and fringe benefit costs for workers grew $116.3 million.

Interestingly enough, the much maligned Department of Motor Vehicles has seen a decrease in inflation-adjusted spending over the past 18 years.

Gov. Malloy halted over 400 infrastructure projects in January of 2018 in an effort to slow down the state’s transportation spending, but expenses are projected to continue growing.

The Office of Policy and Management projects STF revenue to increase from $1.5 billion to $1.8 billion by 2022, according to the December 2017 report.

Debt service costs are expected to increase rapidly, however, from $614 million to $885 million and operating costs, which include the fringe benefits, are projected to grow from $896 million to $1.02 billion by 2022.

Gov. Malloy has made public transportation the hallmark of his administration, building and expanding the CTFrastrak bus line and recently completing the Hartford Line commuter train with service from New Haven to Springfield, Massachusetts.

The governor also launched his Let’s Go CT! infrastructure initiative — a 30 year, $100 billion statewide plan. Some of those projects have been scaled back in light of the STF’s fiscal problems.

CTFastrak cost $567 million to build and requires $17.5 million in public subsidies per year. The Hartford Line cost more than $700 million to construct. Although it is too soon to know the ongoing yearly costs of running the Hartford Line, the state estimated ridership to be 2,428 people per weekday.

Connecticut also owns and maintains the New Haven line of Metro-North in partnership with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which carries over 125,000 people per weekday.

The construction costs for the new bus and rail line were bonded, adding to debt service costs, although the federal government also paid for part of those projects.

The increase in fringe benefit costs can largely be attributed to Connecticut’s unfunded pension liabilities, which drive up labor costs. Past administrations and union leaders agreed to underfund the state pension plans, leading to an explosion of pension debt costs for the state.

Although future projections look daunting for the STF, legislative and market changes averted some pain for bus and train commuters and resulted in a surplus of transportation funding

As part of a bipartisan budget fix passed in May, lawmakers added $29 million to the STF to prevent fare increases on state buses and trains, along with an additional $250 million in general obligation bonds.

The STF will also have a surplus of $117 million this year due to higher gasoline and oil prices which resulted in higher revenues from Connecticut’s Oil Companies Tax, according to Connecticut State Comptroller Kevin Lembo.

Although legislation to further study tolling in Connecticut did not come to a vote during the 2018 session, Malloy’s executive order will bond $10 million to force the study.

A previous comprehensive tolling study by CDM Smith, published in 2015, estimated tolling revenue would be more than $1 billion per year, with 70 percent of the revenue coming from in-state commuters.

Malloy has directed the new study to examine ways in which Connecticut drivers could receive a discount in order to gain more revenue from out-of-state drivers.

Republican leaders sharply criticized Malloy’s order, with House Republican Leader Themis Klarides, R-Derby, calling it “frivolous, if not ridiculous,” and Senate Co-President Len Fasano, R-North Haven, called it “irresponsible and egotistical.”

However, the $10 million bond is expected to pass with only two Republican voices on the bond commission to stand in opposition.

In a break with the governor, Comptroller Lembo said he will also vote against the bond, saying such matters should be decided by the legislature.