The Transportation and Climate Initiative, which would cap the amount of emissions Connecticut generates through gasoline and diesel sales, could underfund Connecticut’s struggling Special Transportation Fund by $500 million, according to numbers crunched by the Connecticut Energy Marketers Association and reviewed by the regional New England Convenience Store and Energy Marketers Association.

Under the TCI program, Connecticut’s transportation emissions will be capped and then lowered year over year, requiring gasoline wholesalers and distributors to purchase emission credits at auction, but, according to CEMA, the cap means less gasoline and diesel fuel available for purchase.

TCI is designed to lower emissions through reducing the amount of gasoline and diesel used by residents of participating states and investing auction proceeds in things like electric vehicle infrastructure, electric buses, public transportation and climate justice initiatives for communities with poor air quality.

Proponents point out that most of Connecticut’s emissions come from the transportation sector, meaning cars and trucks on the road, and the goal of both the program and Gov. Ned Lamont is to reduce transportation emissions by 26 percent over ten years.

However, proponents also claim the program is not meant to reduce driving through higher gas prices because the projected gasoline price increases are too low to actually change drivers’ behavior but is rather meant to encourage electric vehicle usage and the use of public transportation.

Either way, if the program is passed by the General Assembly and proves as effective as its proponents hope, Connecticut’s transportation funding could face some problems, according to CEMA’s analysis.

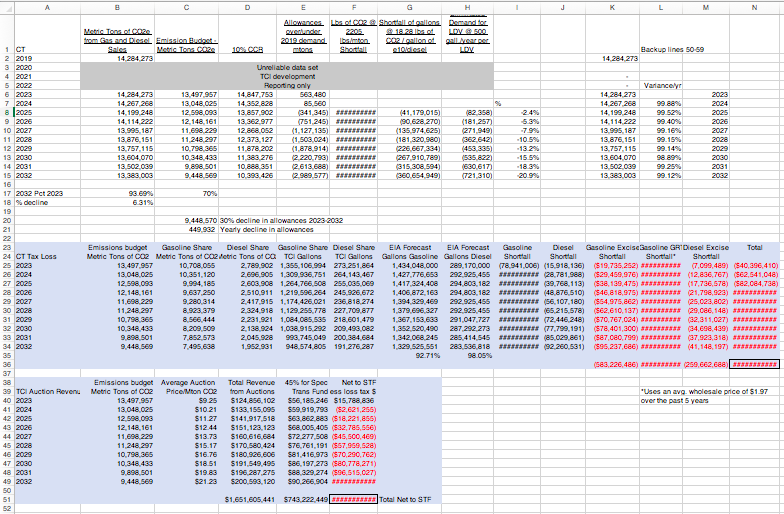

According to TCI’s Elements of Program Design, the starting cap for transportation emissions in Connecticut is 13.4 million metric tons of CO2.

But the term “emissions” is really just another word for fuel. A cap on emissions is a cap on the amount of fuel that can be sold in the state and the TCI program only allows companies to purchase limited offsets in order to gain more emission credits.

Offsets allow a company to invest in other “green” programs or technologies elsewhere to make up for the emissions they produce. TCI allows offsets for methane reduction and capture, along with forest management and reforestation.

Using the most recently available fuel usage data from the Energy Information Administration, CEMA found that Connecticut’s transportation sector produced 14.2 million metric tons of CO2 in 2019, so the initial cap would mark a roughly 5 percent reduction in allowable emissions from a normal year (the 2020 COVID pandemic dramatically reduced driving and commuting).

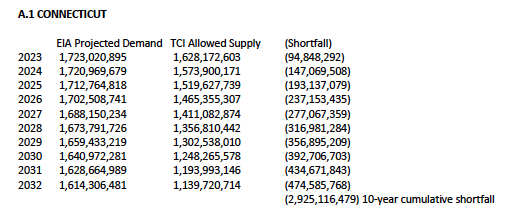

Based on the EIA’s projections of fuel usage in Connecticut, the state would see a shortfall of 78.9 million gallons of gasoline and 15.9 million gallons of diesel in the first year of the program, according to CEMA’s analysis, and less fuel available for purchase means less fuel tax revenue to the Special Transportation Fund.

TCI’s cost containment reserve will allow auctioning off an additional 10 percent of the state’s allowable emissions if auction prices reach a particular price point. TCI also allows a secondary market for emission credits, meaning that distributors and wholesalers can buy, trade or bank emission credits between themselves, potentially driving fuel prices up further, but the secondary market would not affect the emissions cap.

The emissions cap will then be lowered year over year to assure Connecticut reaches its emissions reduction goal.

“The program is designed to lower emissions and the only way you can do that is if you get people to consume less fuel,” said Chris Herb, President of CEMA. “The exact intention of the program is to reduce the amount of fuel that is available because if you don’t burn the gallon you don’t emit CO2 so the only way to do that is make it not available.”

Herb says, historically, Connecticut sells about 1.6 billion gallons of fuel per year. “By year three we will not be able to sell 1.6 billion gallons of fuel because there will not be enough CO2 credits to offset that 1.6 billion,” Herb said.

CEMA calculated the total revenue loss to the STF at potentially $1.23 billion, while the proceeds from TCI would net $743 million over ten years, leaving a loss of roughly $500 million over a ten year period.

“We need to be able to access these credits in order to sell gallons,” Herb said. “If there are less and less credits in the future and there are no credits to buy in the auction, that means gallons that can’t be sold at the pump and that causes the shortage.”

CEMA based their calculations on numbers from the Energy Information Administration, TCI’s emissions caps and Connecticut’s taxes on fuel. The calculations do not include the cost containment reserve established by TCI because the reserve won’t be initiated every year, according to their analysis. They also use a five year average for the price of fuel to calculate the petroleum gross receipts tax. Fuel prices, however, have been rising rapidly over the course of 2021.

Less gasoline and diesel fuel available for purchase means less revenue for the state’s beleaguered Special Transportation Fund, which is already projected to go broke in the next few years. Gov. Ned Lamont has proposed both TCI and a highway use tax on trucks as a means of bolstering the STF and leveraging federal transportation funding and loans.

TCI is expected to bring in between $87 million and $117 million to the state per year between 2023 and 2032, according to the governor’s budget projections. However, half of the proceeds will be essentially earmarked for cities under guidance by an Equity Advisory Board and an additional 5 percent will used for administration, leaving 45 percent for the state.

Revenue from TCI would not go directly into the STF but rather into a different fund called Transportation Grants and Restricted Funds. The money is not counted as revenue toward the STF but would rather decrease the expense side of Connecticut’s public transportation system, according to Lamont’s budget proposal.

However, two of the STF’s largest revenue sources – the state motor fuels tax and the petroleum gross receipts tax – could be affected by reduced gasoline and diesel availability and consumption.

Connecticut imposes a flat 25 cent tax on gasoline purchases, a 44.6 cent tax on diesel and an 8.84 percent petroleum gross receipts tax that only applies to the first $3 dollars of gasoline, according to the Office of Legislative Research.

Those flat or capped taxes mean that even if fuel prices rise, tax revenue could fall short.

Herb says that the Office of Fiscal Analysis did not calculate the effect of reduced allowable fuel sales versus the revenue that would come in from TCI auctions when they crafted the fiscal note for TCI’s enabling legislation. “They didn’t do that work,” Herb said, “and now legislators are flying blind toward a vote.”

Yankee Institute reached out to the Connecticut Department of Transportation for comment on how TCI will affect fuel availability or revenue to the Special Transportation Fund but the department did not respond.

The New England Convenience Store and Energy Marketers Association sent a letter to legislative leaders in Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts outlining their argument that TCI will lead to gas shortages and reduced fuel tax revenue and calling for more study before moving forward with the program.

Supporters of TCI point to the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative — a regional cap and trade program that applies to electricity generation — as proof that cap and trade or cap and invest systems work. CEMA, however, says the comparison is flawed because utilities function basically as “monopolies,” can purchase offsets and bring in electricity from other sources.

“Instead of being creative and figuring out a pathway that works for competitive free market fuel, they got lazy, took a utility model, laid it over a free market situation,” Herb said. “It will lead to deficiencies in the amount of fuel available that the public demands.”

California also has a similar program to TCI but Herb says that comparison isn’t applicable because California’s program is economy-wide, rather than focused only on transportation, and there are more than enough credits to go around with extensive offset opportunities.

Connecticut’s revenue from gasoline sales has remained flat over the past decade and lawmakers pointed to the lack of growth in fuel tax revenue as a reason for trying to get tolls placed on Connecticut’s highways.

Between 2010 and 2019, Connecticut’s revenue from the motor fuels tax went from $469.7 million in 2010 to $464.2 in 2019, according to the Department of Revenue Services’ annual reports, although there were several years in which the revenue was higher, including 2018 which saw $497.8 million in motor fuel tax revenue.

However, limiting fuel sales or increasing electric vehicle usage could be akin throwing water on the Special Transportation Fund’s dying fire, as the EIA forecasts that Connecticut’s gasoline consumption will naturally decline 7.2 percent over the next ten years and diesel consumption will decrease by 1.95 percent.

Similarly, the governor’s economic report found Connecticut drivers are more efficient, using only 425.9 gallons of gasoline per capita as opposed to the rest of the country, which consumed 444.3 gallons per capita.

“As one of the smallest and most densely populated states in the nation, Connecticut residents generally commute shorter distances to work and shop,” the governor’s economic report says. “Per capita consumption reached a peak in 2005, and has fallen faster in Connecticut than in the U.S. since then. Between 2005 and 2018, per capita consumption decreased by 7.5% in Connecticut, versus 6.3% for the nation.”

TCI claims the program will reduce Connecticut’s transportation emissions by 26 percent by 2032, however the organization also notes that emissions will naturally decline by 24 percent as vehicles become more fuel efficient and more people switch to electric vehicles.

During a press conference expounding the benefits of TCI, co-chair of the legislature’s Transportation Committee Sen. Will Haskell, D-Westport, said “We’re helping people get out of their cars and onto public transit.”

“When we invest in EV infrastructure, we’re encouraging people to abandon their internal combustion engines and instead move into this 21st century technology,” Haskell said.

But if TCI is effective at getting people out of their traditional cars and onto public transportation or into electric vehicles, the state’s transportation fund could be left in greater need of additional funding.

That could be where Lamont’s highway use tax on trucks comes in, with an additional $90 million per year by 2024, if passed.

Republicans and No Tolls CT have been holding rallies across the state pushing back on both TCI and the highway use tax, which they are labeling a gas tax and a food tax because the increased costs of transportation will trickle down to both the gas pump and the cost of getting goods to market.

Herb believes gasoline shortfalls will ultimately lead to either Connecticut dropping TCI as drivers no longer have enough gasoline available for purchase or a series of constant “tweaks” to the system allowing more credits to be purchased but then effectively killing the program’s goal.

He also believes passage of the program will set lawmakers up for a future debate over gasoline taxes or possibly tolls when revenue to the Special Transportation Fund falls short.

“This exacerbates the Special Transportation Fund problem and it politically sets them up for another vote on tolls or something else,” Herb said.

Mark

June 1, 2021 @ 11:07 am

I just want to point out that the state of CT made over 460 million in gas taxes which are supposed to go DIRECTLY to pay for infrustructure. What the article leaves out is that basically none of this money was spent on what it was intended for and the people of CT are now being asked to pay MORE because of BAD spending policies. You took in over 460 million for roads and infrustructure, spend that on the roads, fix your other budget issues and stop trying to find new ways to put your hand in the pockets of your citizens. This TCI is a terrible idea, raising gas taxes is a bad idea, raising any taxes in CT is a BAD idea. Take the money you have and create a budget based on those numbers!!! 460++ mil is more then enough if you don’t take from that money to pay for your other bad decisions!