Connecticut has a problem with its major cities.

In two separate 2025 WalletHub studies, Bridgeport, Hartford, New Haven, Stamford, and Waterbury were among the least affordable housing markets in America. Moreover, Bridgeport and New Haven received the added distinction of being some of the worst places to raise a family.

High cost-of-living and taxation, unfriendly business climates, poor performing school districts, and high crime are merely several contributing factors to the cities’ low rankings, according to WalletHub analyst Chip Lupo.

“The issues stem from deeper, long-standing economic and social struggles,” Lupo told Yankee Institute. “Families often face financial instability due to scarce, low-paying jobs and subpar school systems. Healthcare and affordable childcare remain difficult to access, and recreational opportunities for children are limited. In addition, the business environment is hindered by high costs and lack of resources, resulting in slower growth and fewer opportunities.”

Conversely, Connecticut also boasts some thriving urban communities. West Hartford ranked 19th overall in U.S. News & World Report’s “250 Best Places to Live in the U.S. in 2025-2026,” the highest for any Connecticut city. Meanwhile, Danbury was included in Livability’s “Top 100 Best Places to Live in the US in 2025”; and Stamford placed 88th in Niche’s “2025 Best Cities to Live in America.”

In short, there are vast socioeconomic disparities existing between Connecticut’s ten most populous urban centers. While cities like Stamford, West Hartford, and Greenwich are considerably affluent, educated, and economically viable, others such as Bridgeport, New Haven, and Waterbury have had impoverished communities for decades.

Yet cities are epicenters for economic, political, educational, and recreational activities. A good one, as Aristotle examined thousands of years ago in Politics, even establishes a more virtuous society, providing the means for an individual to pursue happiness and self-sufficiency — or, in a modern context, the ability to achieve the American Dream.

Healthy cities improve a state’s overall well-being: attracting new industries, populations, and innovation. Therefore, understanding the challenges and remedying the root causes plaguing Connecticut’s cities must be grappled with if we are to be a state where people want to stay, grow, and thrive.

The Cities Who Failed to Reinvent Themselves

For nearly a century, between the American Civil War to World War II, Connecticut was a “manufacturing juggernaut,” as described by CT Visit.

This is not an understatement. New Britain was known as ‘The Hardware City,’ Bridgeport was an economic hub, and Hartford was famously dubbed the “richest” city in America. Prominent industrial companies like Pratt & Whitney, the U.S. Rubber Company, American Brass, Scovill, Chase Brass and Copper Company, Remington Arms, Colt Firearms, Winchester Repeating Arms called the Constitution State home. Waterbury — the ‘Brass City’ — was so productive that during WWII the Nazis intended to bomb it to hurt the Allied Powers’ war efforts.

Today, however, the cities are littered with abandoned, crumbling factory buildings: remnants of a bygone era. As NBC News reported in 2013, they “failed to reinvent” themselves “with changing tax incentives and the loss of major industry.” Worse, middle-class families “shorn of manufacturing jobs” and “spooked by rising crime rates” fled for surrounding suburban towns.

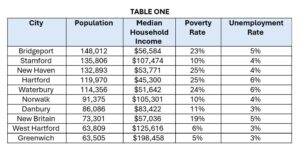

That was more than a decade ago — yet the struggles remain for those who have stayed behind. Hartford, New Haven, Waterbury, Bridgeport, and New Britain are burdened by high poverty rates, several exceeding 20%, according to CT Data. (For context, the state average is 10%.) Additionally, the median household incomes for several Connecticut cities fall well below the 2023 U.S. national average of $80,610; but cities like Stamford, Norwalk, Danbury, West Hartford, and Greenwich far exceed the median household income average. (See Table One)

A void was created that new industries and middle-class families never filled. This has been difficult to accomplish due to “high office-space costs, labor expenses, and corporate taxes,” Lupo told Yankee Institute. For the struggling cities, he argues they have shown “weak performance in fostering a supportive environment for startups and small businesses,” which, in turn, “create a heavy financial burden for entrepreneurs” and “limited investor access.”

“These constraints reduce networking potential, limit industry diversity, and make attracting and retaining talent difficult, all of which dampen the entrepreneurial ecosystem,” Lupo told Yankee Institute.

That ecosystem is burdened by one of the nation’s worst tax climates. According to the Tax Foundation, Connecticut ranks 47th overall when compared to other states due to a high corporate tax rate (31st) and property taxes (50th).

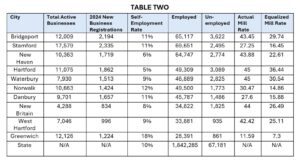

Still, in 2024, Stamford had more than 17,000 active businesses and 2,335 new business applications, the most of the top ten most populous cities (See Table Two). It also had the most employed population at 69,651; and Greenwich had the highest self-employment rate at 18%.

Coincidentally, Greenwich and Stamford had the lowest actual and equalized mill rates (See Table Two). The two highest, meanwhile, were Hartford and Waterbury, followed by New Britain and Bridgeport — though the latter had the second most new business registrations.

High tax rates and labor costs are barriers to investments and inflowing capital, thus spiraling communities into economic despair and/or stagnation. It stands to reason that productive, well-paying industries attract more talent and people who then want quality amenities and recreational spaces.

Ultimately, good jobs breed a stable city. The lack thereof breeds social ills like poor schools, high crime, and government inefficiency.

The Socioeconomics of the Cities

A good education is a building block for an individual’s success in life. Sadly, the opposite is also true: a poor education can set a person toward a life of limited economic opportunities and lower wages, but even a shorter life expectancy.

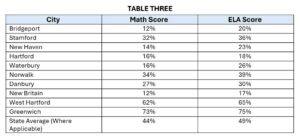

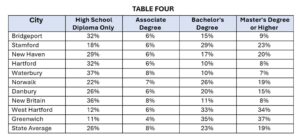

Unsurprisingly, Connecticut cities with a higher median household income have higher education test scores (See Table Three) and are more likely to have a college degree (See Table Four). Greenwich had the highest percentage of public school students who either met or exceeded expectations in 2023-2024, according to CT Data. Bridgeport and New Britain had among the lowest.

Yet Connecticut is a state of contradictions when it comes to education. On the one hand, it boasts some of the wealthiest schools in the United States, particularly in Fairfield County. Conversely, the state suffers from one of the nation’s highest “education gaps” between high- and low-income households.

In short, there is educational inequality in Connecticut with students trapped in public schools that are systematically failing them. One such case that has caught national attention is Aleysha Ortiz — a former Hartford Public Schools student — who claims she can’t read, struggling with even one-syllable words. Nevertheless, she graduated without allegedly receiving any intervention or assistance from district officials. She is now seeking a settlement of $3 million.

But she isn’t alone. According to U.S. News & World Report, only 22% of Hartford’s elementary students and 26% of its middle schoolers tested at or above the proficient level for reading.

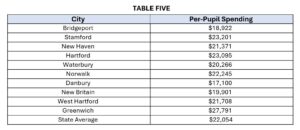

An initial reaction may be to provide more funding to failing school districts; but more spending does not necessarily mean improved results. According to the School + State Finance Project, Greenwich has the highest per-pupil spending at $27,791. While the city has the best test results, at least among the ten most populous Connecticut cities, Hartford is third highest in expenditures but had the fourth worst Math and second worst ELA scores (See Table Five).

A better solution, then, is educational opportunity and access, providing a means for children to escape school districts failing to meet their individual needs. For example, tax credit scholarships have had measurable, academic benefits and improved performance for both public and private school students.

Yet, as previously stated, cities like Bridgeport and New Haven not only suffer from low test scores but are among the least affordable housing markets in America. The Connecticut Business & Industry Association (CBIA) argued in a recent study that the state has a housing shortage, which reaps several economic costs like:

“…reduced workforce availability as potential employees are priced out of job centers; increased business operating costs; suppressed consumer spending as housing costs consume larger portions of household budgets; and diminished economic mobility that threatens future growth.”

However, a 2024 Yankee Institute report, Getting a Handle on Affordable Housing, shows that the state is not necessarily undergoing a housing shortage because the state government does not measure how much affordable housing has been built. Rather, the housing that counts as affordable under Connecticut law is housing that receives a federal or state government subsidy.

Moreover, policymakers should distinguish between affordable housing and housing that is affordable for people of modest means. Yankee Institute’s report emphasizes that the legislature should work toward “[r]educing supply and labor costs” by accepting out-of-state credentials for trade workers, waiving hiring restrictions for apprenticeships, and eliminating ‘prevailing wage’ requirements and onerous building codes.

Labor and regulations, as well as land costs, are contributing reasons why “Connecticut is the seventh most expensive state in which to build a home,” according to New Home Source.

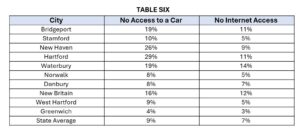

Nevertheless, an individual who can afford and maintain a stable home or apartment is more likely to be self-sufficient — or even have access to a car or the internet (See Table Six).

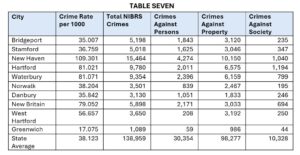

Again, it seems logical that a less educated and/or unstable housing climate will beget more crime. Among the ten most populous Connecticut cities, New Haven has the highest crime rate per 1,000, according to a 2024 report compiled by the Connecticut State Police. The lowest, predictably, is Greenwich (See Table Seven).

Poor public schools, unaffordable housing, and high crime are, no doubt, detractors for middle-class families or business investors to establish roots in urban centers. As Lupo told Yankee Institute:

“Socio-economic issues such as high poverty rates, unemployment, and fewer stable two-parent households further strain affordability and overall family well-being. Long commutes and a lack of recreational spaces also reduce quality of life, making these cities less attractive for families looking to settle down.”

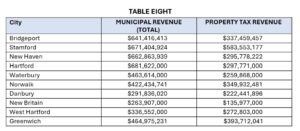

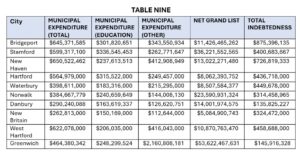

City finances are also a key indicator. Bridgeport expends more than it receives in revenue, contributing to its total indebtedness — the highest among the ten most populous Connecticut cities — and its weak A3 Moody and A S&P ratings (See Tables Eight and Nine). Stamford, meanwhile, has one of the better municipal and property tax revenues and lower indebtedness, but a high net grand list (i.e., taxable property in a municipality). Low and/or weak ratings matter because they signal to businesses that the city has a higher chance of defaulting on its debt, thus becoming a riskier financial investment.

Certainly, Stamford benefits from its proximity to New York — indeed, location is another factor for a city’s prominence and attractiveness to working professionals, families, and businesses. But coupled with lower taxes (See Table Two) and better schools than Bridgeport, Waterbury, New Haven, and Hartford, Stamford is a viable option for economic development from which other benefits and amenities grow.

What Can Be Done?

Lamenting Connecticut cities’ woes is nothing new. In 2001, the Brookings Institute found “they have a deeper crisis rooted in market irrelevance and social isolation,” highlighting how Hartford lost 13% of its population and 11.5% of its job base in the 1990s. Meanwhile, in 2017, Yankee Institute released a study, Connecticut’s Broken Cities: Laying the Conditions for Growth in Poor Urban Communities, examining how the state’s “largest cities have languished” due to “high rates of poverty and crime” and “serious fiscal insecurity.”

That same year, The Atlantic reported that the state was “floundering” because of an exodus of corporations — like General Electric (GE) and Aetna — and population. Since 2000, corporate headquarters for United Technologies/Raytheon, Stag Arms, Edible Arrangements, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, and the LEGO Group have also left, though not all to tax havens. LEGO, for instance, is shipping its U.S.-based headquarters to Boston, Ma., by the end of 2026, which has a comparable burdensome tax climate.

Some of these businesses called Connecticut home for more than a century. For instance, Winchester — established in New Haven in the mid-19th century — shuttered its doors in 2006 after “many efforts were made to improve profitability” in Connecticut. However, the cost of doing business in the state was too much. The ramifications of its departure left “scars” that “still linger in New Haven’s struggling neighborhoods,” according to Yankee Institute Labor Fellow and former New Haven Firefighter Frank Ricci in a May 2025 article.

To quantify the decline in Connecticut’s manufacturing industry sector, since 2000, the state has lost nearly 80,000 jobs — with 233,900 in January 2000 and 154,300 in March 2025, according to Connecticut Labor. And since last year, there are 2,800 fewer manufacturing jobs (157,100 in January 2024 and 154,300 in March 2025).

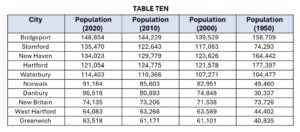

Meanwhile, the results for overall population growth have also been mixed. While Connecticut’s population increased by 32,046 residents between July 1, 2023, and July 1, 2024, most were international immigrants. Concurrently, more than 21,000 people moved out of state to escape high taxes, according to a March report by the Heritage Foundation, If You Tax Them, They Will Run: Millions of Americans Flee from California and New York. Moreover, several Connecticut cities are still below their population size after the Second World War, according to U.S. Census data. (See Table Ten)

Connecticut has had poor population growth performance in part due to having one of the most expensive electric rates in the nation, second only to Hawaii; and being one of the worst places to retire and to start a business, among other indicators. Yet despite the state’s heavy tax burden, Connecticut has one of the weaker returns on investment (ROI) for quality government services. In short, residents and businesses are paying more for less.

It’s human nature to move to where the ‘grass is greener’: to find good-paying jobs, safer neighborhoods, better schools, and fewer taxes and cost-of-living expenses. Even escaping onerous traffic surrounding cities — which Connecticut’s I-95 and Merritt Parkway are nationally ranked among the most congested — may persuade more people to flee or dissuade investment.

But what can be done to help the “floundering” cities? Some may suggest more affordable housing units or investing more in education in impoverished urban centers. However, Connecticut already has a high cost-of-living — and more taxation to provide government services for struggling cities will not improve the likelihood of families and businesses settling here. In fact, the opposite is true.

Instead, as Lupo told Yankee Institute, cities need to “boost business growth” by “lowering costs such as office rentals and labor, increasing access to financing and investors, and diversifying their local economies.” Moreover, he suggests, “Providing support for startups through mentorship and networking can help build stronger business communities” and “[i]nvesting in workforce development to attract and retain talent is also key to creating a more vibrant environment for new businesses.”

To be economically viable, cities must also consider ways of attracting middle-class families by creating a safe, clean, and stable environment — and offering hope for a better future. After all, a great city inspires innovation and progress; a bad one stokes despair. And as evidenced in several Connecticut urban centers, economic strife is the root of many social problems.

Though there are no easy fixes, a good place to start is to not punish prosperous communities via higher taxes and/or burdensome housing regulations, but to lay the groundwork for economic and social opportunities as Lupo indicated to Yankee Institute.

Connecticut cities were once juggernauts of industry, but this is not ancient history. And there have been encouraging signals of overall job growth as the state added 16,000 jobs last year.

With the dawn of artificial intelligence and other emerging industries, as well as its location between expensive cities like New York and Boston, the Constitution State is poised to become an economic hub if it reforms its finances and regulations. Indeed, if Gov. Ned Lamont wants working professionals, families, and businesses to “Make it Here” as his economic campaign suggests, then the state needs to implement common sense, free market principles to provide the space for our cities to become economic powerhouses again.

If so, there is no telling how it will impact peoples’ lives — and make Connecticut a state where one can stay, grow, and thrive.

Robert Ham

June 25, 2025 @ 6:22 am

Well done Mr. Fowler!!

The governor has the chance to be a leader by taking this analysis as a good top level document and making it his business to reduce the costs of government.

When per-capita costs of the annual budget in CT (@$7,700) start to drop to the level of nearby New Hampshire (@ $4,500 per capita), then CT will become more attractive to individuals and businesses that want or need to be here – with proximity to NYC and BOSton.

Alas – political leadership in CT caters to union bosses whose only play book is “us against them”, with the them being the tax-payer.