In the darkness of early morning, June 6th, 1944, Robert Hillman, a 20-year-old private from Manchester, Conn., boarded his assigned C-47 aircraft along with other members of the 101st Airborne. He was one of more than 13,000 American paratroopers to do so among the thousand planes that morn.

Their mission: the “elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world,” Gen. Dwight Eisenhower’s order stated for that day. Hillman, embarking on that Great Crusade, was a small part of the largest invasion force ever deployed in world history before or since.

A graduate of Manchester High School in 1942, where he was a football and cross country athlete, Hillman enlisted the following November, passing the tests to become a paratrooper. He was sent overseas in November 1943.

Despite nearly two years of training, the young man was no doubt nervous, much like his brothers in arms on D-Day. Yet, as he made a final inspection of his parachute gear, he guffawed, breaking the tension, albeit momentarily. “I know my chute is okay,” he said. Coincidentally, NBC war correspondent Wright Brown, who was on the plane, asked the paratrooper how he could be so sure. Hillman responded, “Because my mother checked it. She works in the Pioneer Parachute Company in our town and her job is to give the final once over to all chutes they manufacture.” He revealed his mother’s initials to Brown — she used them as her stamp of approval.

It has been 80 years since Hillman made that jump over Normandy, France. Although he sustained injuries, he did survive D-Day and the war.

Certainly, this tiny and coincidental moment before one the greatest military endeavors in human history reflects the significant impact of Connecticut’s contributions — both in valor on the battlefield and production of military materials — to the eventual defeat of the Axis Powers in World War II.

From North Africa to Europe to the Pacific, more than 200,000 men from Connecticut, like Hillman, joined the efforts to fight for freedom, and 4,500 made the ultimate sacrifice in combat, with another thousand dying from disease or accidents. Meanwhile, the state’s industries were vital to the Allied cause, so much so that Waterbury was “believed to be a strategic bombing target for the German Luftwaffe,” according to Ken Burns’ documentary, The War.

This is the story of Connecticut during World War II.

‘Once More Unto the Breach’

War had engulfed Europe several years before Dec. 7, 1941, when the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Though there were strong isolationist sentiments throughout the country and a veil of neutrality, the U.S. government had been providing aid to the United Kingdom and others through the Lend-Lease program, where America would lend “Great Britain the supplies it needed to fight Germany, but would not insist upon being paid immediately,” according to the U.S. Department of State’s Office of the Historian.

Yet the “day of infamy,” as President Franklin D. Roosevelt described the attack, thrust America into the conflict outright. More than 2,400 service members and civilians died in the air raid, including nearly 30 from Connecticut. Several native sons from Bridgeport were killed on the USS Arizona. Amidst the mayhem, Thomas J. Reeves from Thomaston — and a Warrant Officer 1 in the U.S. Navy — displayed extraordinary courage in the face of certain death. According to his Medal of Honor citation:

“After the mechanized ammunition hoists were put out of action on the U.S.S. California, Reeves, on his own initiative, in a burning passageway, assisted in the maintenance of an ammunition supply by hand to the antiaircraft guns until he was overcome by smoke and fire, which resulted in his death.”

Reeves would be one of eight Connecticut soldiers to receive the military’s highest honor by the war’s conclusion (see below for the other citations).

The attack’s immediate aftermath wrought a slew of emotional reactions, as reflected by the Hartford Daily Courant headlines like: “Await Word of Relatives in War Zone: Families and Friends Anxious About Many Hartford Residents in Hawaii, Orient,” “Full Defeat of Japanese Is Forecast,” and “Stranded Soldiers Hear War News” among others. Meanwhile, the Yale Daily News reported that 1,500 students and locals “stormed the center of the city in a spontaneous demonstration” shouting “Let’s go to Tokyo” and singing the classic George M. Cohen/World War I anthem, “Over There.” Yale alone had more than 18,000 fight in the war and 514 made the ultimate sacrifice.

Unlike the First World War, which ended more than 20 years earlier, the U.S. military and people would endure multiple years of hardship across the world. Some of the horrors Connecticut residents suffered came shortly after Pearl Harbor, including what Everett Roseen of West Hartford endured. Born Jan. 15, 1918, Roseen joined the Army in 1938 and then re-enlisted in early 1941. He was assigned to the Philippines, where he served in the Signal Company tasked to erect radar sets across Luzon. Then Japan invaded; after months of fighting, the U.S. and Filipino forces surrendered Bataan on April 9, 1942. More than 76,000 men became prisoners of war (POWs), including Roseen.

Roseen was forced into what is now known as the Bataan Death March: a hellish 65-mile trek from the Bataan Peninsula to prison camps, with 11,000 prisoners dying en route. As he told PBS in “Battleground: Connecticut During World War II”:

“Some of the men who had high fevers from malaria would have convulsions and just fall and the Japanese would kill them, shoot them. One time, I saw a Japanese soldier, some tanks were coming along, and one man was stumbling along. As he was going to fall, [the Japanese soldier] hit him with his rifle butt and shoved him right out in front of the tanks. Three or four tanks went over him, this man. …The uniform looked like it was pressed in the dirt after they’d passed. I’ll never forget that.”

He survived the march, languishing as a POW for nearly four years. After the war, Roseen remained in the military for another two decades until his retirement.

The experiences, unsurprisingly, varied among the hundreds of thousands of Connecticut men who served their country. For instance, Ward Chamberlin of Norwalk volunteered as an ambulance driver with the American Field Service (AFS), a relief organization that had formed in the First World War. In January 1943, Chamberlin was sent to North Africa and assigned to the British 8th Army; however, he was struck with polio and “given order for one year of desk duty,” according to The War. He ignored the orders, making his way to the front lines in central Italy. As Burns’ documentary describes, Chamberlin “spent four months evacuating the wounded from the brutal battles at Monte Cassino,” promoted to captain, and “served with the 8th Army in Italy until the war in Europe ended.” He was sent to India in June 1945, preparing for an invasion of Singapore that never came to pass. When he returned home, Chamberlin spent most of his professional career in public broadcasting.

In another unique war contribution, Deane Keller — an artist from New Haven and a MFAA officer with the U.S. 5th Army in Italy — “rescued Italian masterworks from the threat of combat and looting,” according to his biography in the Connecticut Hall of Fame. As to what that encompassed, the Monuments Men and Women Foundation explains that Keller “was part of the team that triumphantly returned the Florentine museum treasures to the city in 1945,” and that arguably “his most valiant effort was made in Pisa at the ancient cemetery structure called Campo Santo,” saving frescoes in the building. He was awarded the U.S. Legion of Merit among other distinctions.

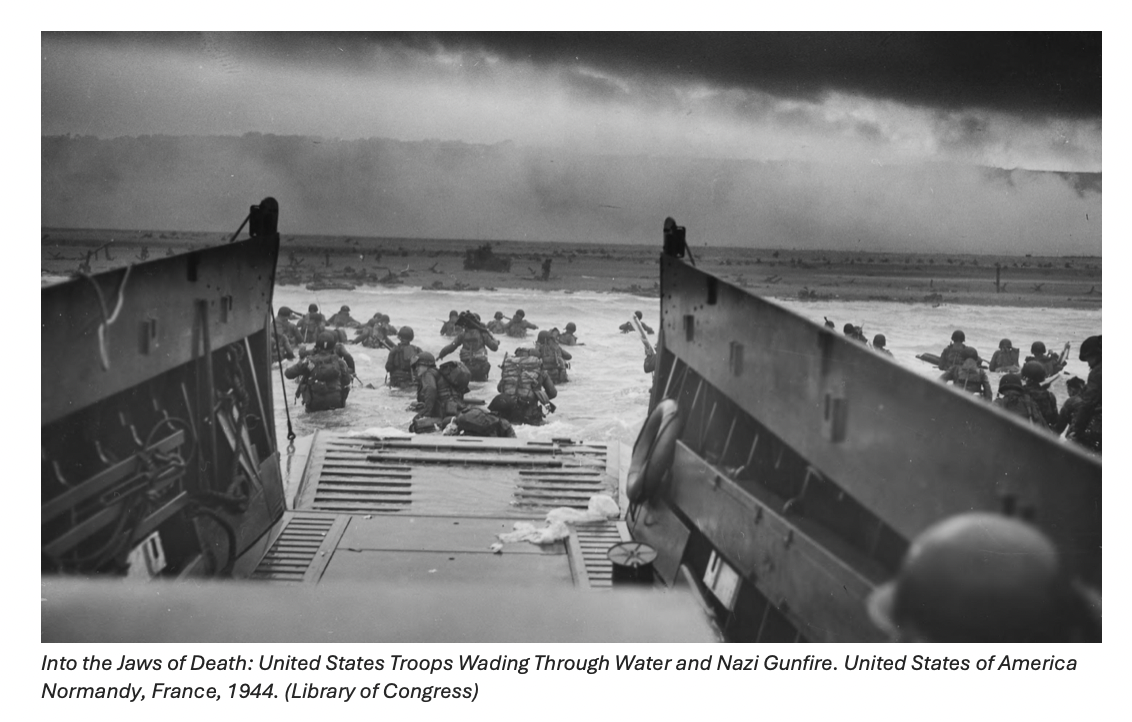

On D-Day, Joseph Vaghi of Bethel oversaw Company C, 6th Naval Beach Battalion, using “flags, blinkers, and a megaphone to get men, vehicles and supplies safely ashore on Omaha Beach,” according to The War. Under heavy fire, he and his men “ran several hundred yards” and went on “directing his men, struggling to clear a path off the beach, helping the wounded and the dying.” During the battle, he was knocked unconscious by German artillery — and when he regained consciousness, Vaghi realized “his clothes were on fire and he was wounded in the knee.” But as his testimony states, he kept going, “struggling to remove cans of gasoline from a burning jeep before they could explode and kill the wounded men lying all around him.” He also assisted in removing barbed wiring that blocked the Allied advance.

Among the many stories from D-Day was also the remarkable escape of Rollin Booth Fowler (no relation) of Bethany. According to Connecticut History, Fowler — a glider pilot — served as a personal bodyguard for Gen. Eisenhower and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in the lead-up to the June 6th invasion. During the day’s events, he crash-landed in enemy territory and “found himself in the thick of the fight, killing five enemy soldiers with hand grenades and four more with a rifle before the explosion of an enemy grenade knocked him unconscious.” Regaining consciousness, he awoke as a POW, but he would not be one for long. As Germans interrogated him at the Nazi headquarters, Allied planes bombarded the hub, creating mayhem — and Fowler seized the opportunity for an escape:

“[He] found that the soldier who searched him for weapons upon his capture overlooked a hand grenade that Fowler still had in his possession. Throwing the grenade in the direction of the staff car, Fowler killed the colonel and another soldier. He then quickly grabbed the colonel’s binoculars and a carbine and ran down the road where he procured a German motorcycle and used it to race back to the Allied lines.”

On the other side of the globe, in the Pacific Theater, Connecticut men were assembled in the 43rd Division. Absorbing the 102nd and 169th Infantry Regiments (which were historically founded in the Constitution State), the division landed in New Zealand on Oct. 23, 1942. According to “Connecticut National Guard: Colors, Standards and Guidons During World War II,” the 43rd Division, particularly the 169th Infantry Regiment, was instrumental in the invasion of New Georgia — which is part of the Solomon Islands.

Dubbed Operation Toenails, the Solomon Islands were in crosshairs of America’s “island hopping” campaign (liberating conquered territories) after the Japanese evacuation of Guadalcanal in February 1943. On New Georgia, the “most vital objective” was capturing the Japanese airbase at Munda Point, according to The National WWII Museum. However, capturing the dozen islands was “a complicated business, since they were separated by narrow channels where ships would be vulnerable to Japanese shore batteries, and surrounded by coral reefs and barrier islands.”

On July 2, the 43rd Division successfully landed on New Georgia’s southern shore — but they encountered a harsh, swampy, jungle environment that delayed their advance. Meanwhile, the Japanese were “dug in and hidden everywhere,” and, at night, “would get close enough to verbally harass and terrify the men,” as described by the Connecticut National Guard. Friendly fire became a tragic issue among the men: soldiers knifed each other or “threw grenades blindly in the dark,” according to The National WWII Museum. After a brief reprieve from combat, the 169th Infantry Regiment, now regrouped and experienced, participated in the final assault on Munda Field. On August 5, U.S. forces finally “overran” the entrenched Japanese, capturing the airfield. For the rest of the war, the 43rd Division island hopped, securing other strategic points along the way, including taking the Lingayen Plain in Luzon “under enemy fire” on Feb. 12, 1945, and smashing Axis resistance at Ipo Dam in the Philippines on May 19 later that year.

There is a plethora of testimonies worthy of their own, individual entries. Hidden in the Oak has already covered some accounts of World War II, including that of Capt. Henry Mucci of Bridgeport, who led “The Great Raid,” rescuing 500 American prisoners at the Japanese POW camp in Cabanatuan. Still, the actions on battlefields throughout the war are a testament to the mettle of our state’s brave service members. Here are others who served valiantly, many sacrificing their lives (these are lightly edited Medal of Honor citations):

William Grant Fournier

Fournier served in the Pacific Theater with Company M, 35th Infantry and the 25th Infantry Division. On Jan. 19, 1943, at Mount Austen in Guadalcanal, he was leading a machine-gun section charged with the protection of other battalion units. His group was attacked by a superior number of Japanese: his gunner was killed, his assistant gunner was wounded, and an adjoining guncrewwere put out of action. Ordered to withdraw from this hazardous position, Sgt. Fournier refused to retire but rushed forward to the idle gun and, with the aid of another soldier who joined him, held up the machine gun by the tripod to increase its field of action. They opened fire and inflicted heavy casualties upon the enemy. While so engaged both these gallant soldiers were killed, but their sturdy defensive action was a decisive factor in the following success of the attacking battalion.

William James Johnston Sr.

On Feb. 17, 1944, near Padiglione, Italy, Johnston observed and fired upon an attacking force of approximately 80 Germans, causing at least 25 casualties and forcing withdrawal of the remainder. The entire day he manned his gun without relief, subject to mortar, artillery and sniper fire. Two Germans individually worked so close to his position that his machine gun was ineffective, whereupon he killed one with his pistol, the second with a rifle taken from another soldier. When a rifleman protecting his gun position was killed by a sniper, he immediately moved the body and relocated the machine gun in that spot in order to obtain a better field of fire. He volunteered to cover the platoon’s withdrawal and was the last man to leave that night. In his new position, he maintained an all-night vigil, the next day causing seven German casualties. Onthe 18th, the organization on the left flank having been forced to withdraw, he again covered the withdrawal of his own organization. Shortly thereafter, he was seriously wounded over the heart, and a passing soldier saw him trying to crawl up the embankment. The soldier aided him in resuming his position behind the machine gun, which was soon heard in action for about 10 minutes. Though reported killed, Johnston was seen returning to the American lines on the morning of Feb. 19, slowly and painfully working his way back from his overrun position through enemy lines. He gave valuable information of new enemy dispositions. His heroic determination to destroy the enemy and his disregard of his own safety aided immeasurably in halting a strong enemy attack, caused an enormous amount of enemy casualties and so inspired his fellow soldiers that they fought for and held a vitally important position against greatly superior forces.

Homer Wise

On June 14, 1944, in Magliano, Italy, Wise and his platoon were pinned down by enemy small-arms fire from both flanks. During the firefight, he left his safety position and assisted in carrying one of his men, who had been seriously wounded and who lay in an exposed position, to a point where he could receive medical attention. The advance of the platoon was resumed, but was again stopped by enemy frontal fire. A German officer and two enlisted men, armed with automatic weapons, threatened the right flank. Fearlessly exposing himself, he moved to a position from which he killed all three with his submachine gun. Returning to his squad, he obtained an M1 rifle and several antitank grenades, then took up a position from which he delivered accurate fire on the enemy holding up the advance. As the battalion moved forward it was again stopped by enemy frontal and flanking fire. He procured an automatic rifle and, advancing ahead of his men, neutralized an enemy machine gun with his fire. When the flanking fire became more intense, he ran to a nearby tank and, exposing himself on the turret, restored a jammed machine gun to operating efficiency and used it so effectively that the enemy fire from the adjacent ridge was materially reduced, thus permitting the battalion to occupy its objective. He survived the war, dying on April 22, 1974, in Springdale, Conn.

Frank Peter Witek

Witek posthumously received the Medal of Honor for his actions during the battle of Finegayen at Guam, Marianas, on Aug. 3, 1944. When his rifle platoon was halted by heavy surprise fire from well-camouflaged enemy positions, Witek daringly remained standing to fire a full magazine from his automatic at point-blank range into a depression housing Japanese troops, killing eight of the enemy and enabling the greater part of his platoon to take cover. During his platoon’s withdrawal for consolidation of lines, he remained to safeguard a severely wounded comrade, courageously returning the enemy’s fire until the arrival of stretcher bearers and then covering the evacuation by sustained fire as he moved backward toward his own lines. With his platoon again pinned down by a hostile machine gun, Witek, on his own initiative, moved forward boldly to the reinforcing tanks and infantry, alternately throwing hand grenades and firing as he advanced to within 5 to 10 yards of the enemy position, and destroying the hostile machine-gun emplacement and an additional eight Japanese before he himself was struck down by an enemy rifleman. His valiant and inspiring action effectively reduced the enemy’s firepower, thereby enabling his platoon to attain its objective.

Robert Burton Nett

On Dec. 14, 1944, Nett commanded Company E in an attack against a reinforced enemy battalion which had held up the American advance for two days from its entrenched positions around a three-story concrete building. With another infantry company and armored vehicles, Company E advanced against heavy machine-gun and other automatic-weapon fire with Nett spearheading the assault against the strongpoint. During the fierce hand-to-hand encounter which ensued, he killed seven deeply entrenched Japanese with his rifle and bayonet and, although seriously wounded, gallantly continued to lead his men forward, refusing to relinquish his command. Again, he was severely wounded, but, still unwilling to retire, pressed ahead with his troops to assure the capture of the objective. Wounded once more in the final assault, he calmly made all arrangements for the resumption of the advance, turned over his command to another officer, and then walked unaided to the rear for medical treatment. By his remarkable courage in continuing forward through sheer determination despite successive wounds, Nett provided an inspiring example for his men and was instrumental in the capture of a vital strongpoint.

John Magrath

A private first class, Magrath’s company was pinned down by heavy artillery, mortar, and small-arms fire, near Castel d’Aiano, Italy, on April 14, 1945. Volunteering to act as scout, armed with only a rifle, he charged headlong into withering fire, killing two Germans and wounding three to capture a machine gun. Carrying this weapon across an open field through heavy fire, he neutralized two more machine-gun nests; he then circled behind four other Germans, killing them with a burst as they were firing on his company. Spotting another dangerous enemy position to his right, he knelt with the machine gun in his arms and exchanged fire with the Germans until he had killed two and wounded three. The enemy now poured increased mortar and artillery fire on the company’s newly won position. Magrath fearlessly volunteered again to brave the shelling to collect a report of casualties. Heroically carrying out this task, he made the supreme sacrifice.

Michael Joseph Daly

On the morning of April 18, 1945, Daly led his company through the shell-battered, sniper-infested wreckage of Nuremberg, Germany. When blistering machine-gun fire caught his unit in an exposed position, he ordered his men to take cover, dashed forward alone and, as bullets whined about him, shot the three-man gun-crew with his carbine. Continuing the advance at the head of his company, he located an enemy patrol armed with rocket launchers which threatened friendly armor. He again went forward alone, secured a vantage point, and opened fire on the Germans. Immediately, he became the target for concentrated machine-pistol and rocket fire, which blasted the rubble about him. Calmly, he continued to shoot at the patrol until he had killed all six enemy infantrymen. Continuing boldly far in front of his company, he entered a park, where as his men advanced, a German machine gun opened up on them without warning. With his carbine, he killed the gunner; and then, from a completely exposed position, he directed machine-gun fire on the remainder of the crew until all were dead. In a final duel, he wiped out a third machine-gun emplacement with rifle fire at a range of 10 yards. By fearlessly engaging in four singlehanded firefights with a desperate, powerfully armed enemy, Daly, voluntarily taking all major risks himself and protecting his men at every opportunity, killed 15 Germans, silenced three enemy machine guns, and wiped out an entire enemy patrol. His heroism during the lone bitter struggle with fanatical enemy forces was an inspiration to the valiant Americans who took Nuremberg.

‘We Can Do It!’

The Pioneer Parachute Company’s origins “traces” back to 1838 after five brothers formed the Cheney Brothers silk mill in Manchester, according to Erik Ofgang’s Connecticut Insider article (May 22, 2019). A century later, the company — formerly established under the “Pioneer” name in 1938 — developed into the largest silk mill in the United States with 4,700 workers.

However, before America’s direct involvement in World War II, the company switched to nylon chutes since silk was “becoming more difficult to obtain from Asia,” as Ofgang notes. Yet the material was not proven to be fully effective until June 1942 when Adeline Gray of Oxford, Conn., safely jumped 2,500 feet over Brainard Field in Hartford. Her expertise and derring-do attitude “paved the way for Pioneer to become the world’s leading producer of nylon parachutes by 1942,” and even advertising opportunities (for Camel cigarettes).

Pioneer and Gray are a microcosm of how Connecticut residents on the homefront contributed to their ‘boys in uniform.’ They recognized it was a ‘total war’ — everything and anything would need to be utilized to promote the war effort, including rubber and scrap metal drives, war bond sales and rationing other materials.

In a 1942 proclamation honoring World War I’s Armistice, Connecticut Gov. Robert Hurley sought inspiration from the previous generation’s sacrifice to its country, stating:

“Let us, in the total war that had been thrust upon us, resolve that we shall be a people united, determined to beat back the forces of tyranny and aggression; let us resolve to honor the heroes of the other war by giving our full measure of sacrifice and devotion to the immediate tasks confronting us; let us resolve that a quick victory shall be ours and that a permanent and lasting peace may endure; and let us pray to Almighty God that He may watch and guide us in our fight to preserve our traditional liberties.”

The Connecticut people and businesses took those resolutions to heart. At the war’s outbreak, companies quickly changed their production lines from their regular output to military supplies. Ken Burns’ The War and the University of Connecticut (UConn) Library’s “Homefront: Connecticut Businesses in World War II” extensively explore this rapid adaptation and impact. The former particularly focuses on how Waterbury became a hub for World War II industrialization:

“The Mattatuck Manufacturing Company switched from making upholstery nails to cartridge clips for the Springfield rifle, and soon was turning out three million clips a week. The American Brass Company made more than two billion pounds of brass rods, sheets and tubes during the war. The Chase Brass and Copper Company made more than 50 million cartridge cases and mortar shells, more than a billion small caliber bullets and, eventually, some of the components used in the atomic bomb.”

Additionally, Waterbury Clock constructed a new plant in 1942 to “accommodate the military’s demands for mechanical time fuses and other aircraft and artillery equipment,” as Burns notes. Meanwhile, as UConn’s exhibit highlights, the “labor force seemed to changed overnight.” To fill in for enlisted and/or drafted men, women and African Americans entered the workforce, the latter as the result of an executive order banning racial discrimination. Additionally, Mexican workers — as part of the Bracero Program (which permitted Mexican men to work legally in the United States on short-term contracts) — were employed in Connecticut industries.

Other companies that “retooled” to military production included the E. Ingraham Company and New Britain Company; and, as UConn describes, “utility companies like the Hartford Electric Light Company and the Southern New England Telephone Company redirected their services to support wartime industry.” Meanwhile, Electric Boat produced 74 submarines and nearly 400 PT boats throughout the war’s duration. Pratt & Whitney expanded its workforce from 3,000 to 40,000 employees in order to meet a challenge presented by President Roosevelt to manufacturers to build 50,000 aircraft a year, according to Connecticut History. By 1945, the company produced more than 363,000 aircraft engines — or “an amount equal to one half the total airpower of the Allied Air Forces.”

The exceptional production by Connecticut businesses did not go unnoticed. During the war, state manufacturers were “regularly” recognized for their output and contributions with the Army-Navy Excellence in Production Award, which honored “the top performers of the civilian war industry” in “quality and quantity of production,” according to the New York Historical Society Museum & Library. This award served multiple purposes, UConn suggests, helping to “ease tension between federal agencies newly regulating business operations,” spurring workers to continue their outstanding performance and “boost[ing] morale amid the disruptions to work and daily life.” By the war’s end, nearly 175 companies received the award, placing Connecticut as one of the leading states in country, according to The Newtown Bee.

Of course, the war was not confined only to factories and industries or even to peoples’ own homes (i.e., rationing); it was an ever-present public reality. There was great anxiety among the populace. Anti-aircraft weaponry was stationed near Hartford. A rumor swirled that German U-Boats patrolled the Connecticut River. Communities formed air raid responses in the event of an attack; and even the local barbers in Waterbury “volunteered to equip the city’s barbershops as first aid stations,” according to The War.

To further protect its citizens from a potential air raid by the Luftwaffe, in 1941, the state government purchased 1,700 acres of tobacco farmland in Windsor Locks, which eventually became Bradley Field (known as the Bradley International Airport today). As Connecticut History explores, the new airbase “served as a training post for air combat units, a staging area for overseas military deployments, and a camp for housing German prisoners throughout the remainder of the war.” The base was named after a 24-year-old pilot, Eugene M. Bradley, who tragically died in a training exercise.

On the charitable front, the American Red Cross — as in previous wars — “produced needed materials, visited wounded soldiers and supported home front relief work,” as well as supplying blood plasma to the U.S. military. Likewise, the Knights of Columbus — a Catholic fraternal organization based in New Haven — mimicked its World War I recreational and spiritual outreach to soldiers by establishing “huts” around the world, including England, Iceland, Italy, Hong Kong and the Middle East. They also sponsored a “War Bond Drive” among its members in 1943, with the goal of selling or purchasing $25 million worth in bonds within one month. The K of C ended up surpassing that, eclipsing $90 million, enough to fund projects such as the construction of the SS William Tyler.

A Fading, Living Memory

Nazi Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945; Japan followed on August 14, with a formal surrender aboard the USS Missouri on September 2. In total, more than 400,000 U.S. soldiers died among an estimated 85 million casualties (battle deaths, battle wounded and civilian deaths) throughout World War II.

One such loss from Connecticut included Kenneth McKeeman: a 23-year-old airman who was shot down in March 1944. At the time, his family held a funeral despite the U.S. military not recovering his body. He was lost — accidentally buried in a French cemetery as an “unknown casualty.” However, after 80 years and DNA testing conducted by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), McKeeman is finally heading home to Connecticut. He will be buried at the State Veterans Cemetery in June, according to CBS News.

McKeeman’s journey home shows World War II’s wounds still linger.

The full extent of casualties may never be known for certain — especially when examining the Nazi’s systemic extermination and mass murder of European Jews during the Holocaust, which researchers conclude surpass 6 million (Ultimately, 12 million were killed when accounting for other persecuted peoples based on “biological, racial, political and/or ideological reasons,” according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum). Nicholas Lanteri of Southington witnessed the liberation of one of the more than 40,000 concentration camps. As he shares in “Battlefront: Connecticut During World War II,” he and other U.S. soldiers were “very upset seeing all these bodies that were burnt and in the ovens, that they were also piled up on the beds of the trucks,” adding, “And I know the people today don’t believe that [the Holocaust] ever happened, but it did.” That documentary premiered in 2002.

At the Nuremberg Trials, which prosecuted Nazi officials for war crimes, Thomas J. Dodd — a former U.S. lawmaker from Connecticut and attorney — was the “second ranking U.S. lawyer and supervisor of the day-to-day management of the U.S. prosecution team,” where he “shaped many of the strategies and policies through which the trial took place,” according to the Connecticut General Assembly Office of Legislative Research. Although he was later censured by the U.S. Senate for financial misconduct in 1967, Dodd’s efforts at the trials helped “secure justice for the victims of Nazi crimes,” according to Connecticut History.

Yet a troubling 50-state survey from 2020 by Claims Conference found a “worrying lack of basic Holocaust knowledge” among millennials and Generation Z:

“63 percent of all national survey respondents do not know that six million Jews were murdered and 36 percent thought that “two million or fewer Jews” were killed during the Holocaust. Additionally, although there were more than 40,000 camps and ghettos in Europe during the Holocaust, 48 percent of national survey respondents cannot name a single one.”

Even more disconcerting is that one-fifth of U.S. citizens between 18-29 years old believe the Holocaust is a myth, according to a December 2023 poll conducted by the Economist/YouGov.

This is what happens when living memory fades — and when we take former generations’ testimonies for granted. We are doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past. And more worrisome, a full century has not passed. World War II was a modern war. There is documentation. Evidence. Photographs. Footage. Shoes.

Our brave Connecticut soldiers, who gave their lives, and the dedicated residents who served on the homefront deserve better. The members of our ‘Greatest Generation’ were, indeed, great because of their sacrifice to the country and to freedom: freedom for complete strangers, those who suffered under tyranny.

It is imperative that we, those who follow, carry on their memory and impart an appreciation for the valiant courage they displayed in the face of absolute darkness — and cherish the time we have left with those who lived it.

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler

What neat history do you have in your town? Send it to yours truly and I may end up highlighting it in a future edition of ‘Hidden in the Oak.’ Please encourage others to follow and subscribe to our newsletters and podcast, ‘Y CT Matters.’

Point of personal privilege: One of the honors of my life was interviewing the last known living witness to the German surrender, Louis Graziano. He celebrated his 101st birthday earlier this year. This is his story.