Connecticut’s employment numbers are trailing the rest of the country in all income groups as the state struggles to bounce back from the COVID lockdowns, but the jobs gap remains especially pronounced for low wage workers.

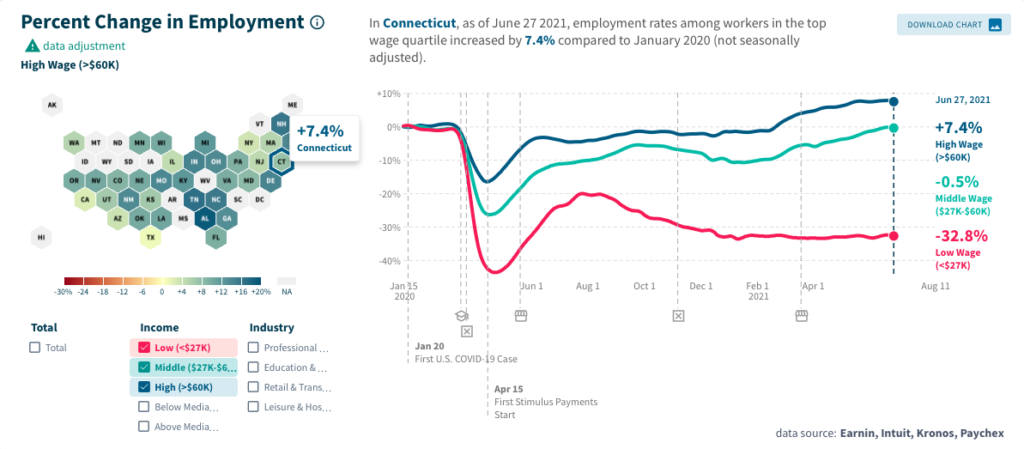

Connecticut’s low wage jobs – defined as those earning $27,000 or less per year – remain 32.8 percent below pre-pandemic levels, according to data compiled by Track the Recovery, a project by Harvard University and Brown University.

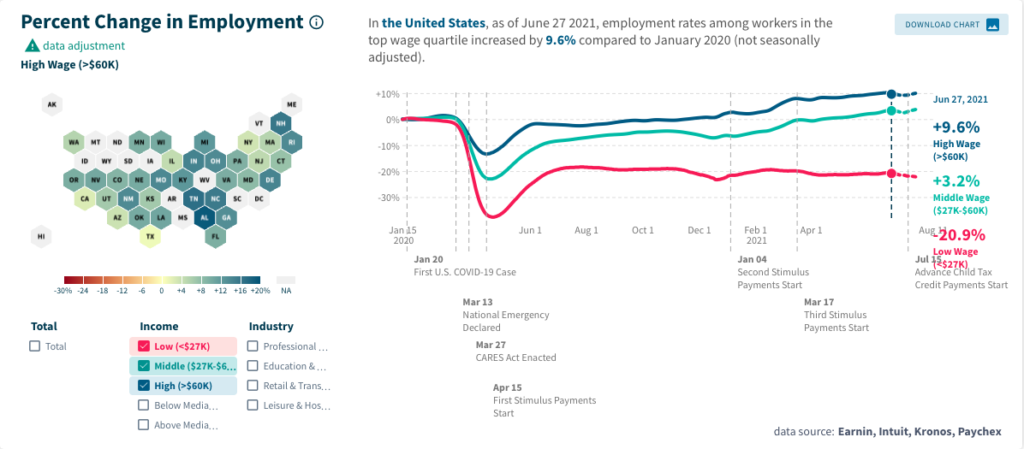

Nationally, those same jobs are 20.9 percent below pre-pandemic levels.

Similarly, middle wage workers earning between $27,000 and $60,000 per year remain down .5 percent whereas nationally those jobs increased by 3.2 percent, and while jobs earning more than $60K per year have seen 7.5 percent increase over pre-pandemic levels in Connecticut, that increase remains 2.2 percentage points lower than the rest of the country.

But the trend among workers on the lower end of the wage spectrum – those most affected by the COVID-19 shutdown of businesses – point to an uneven recovery that remains especially pronounced in Connecticut.

Connecticut, along with New Mexico, currently has the highest unemployment rate in the country and some employers say they are having difficulty recruiting workers for lower-wage jobs.

Connecticut has not yet recovered 100,000 jobs lost during the pandemic and while there were early signs of strong growth, there have also been recent signs of a slow-down in job recovery, with the private sector losing jobs in June.

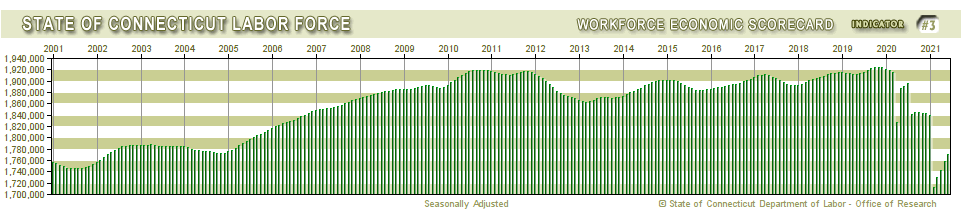

There was also a steep drop off in Connecticut’s reported labor force, which declined from 1.918 million workers as of February 2020 to 1.77 million as of June 2021, meaning that nearly 200,000 workers are either not looking for employment, have retired or left the state and are not counted toward the unemployment rate.

According to the Bureau of the Labor Statistics, there were 10.2 million job openings by the end of June 2021, with increases in professional and business services, retail trade and accommodation and food services, according to BLS Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary.

The causes of the slow recovery among lower wage workers debatable and explanations range from extended federal unemployment benefits in some states to fear of a resurgence of COVID and workers being reluctant to return to low wage jobs without seeing a significant increase in pay.

At the moment, it’s a workers’ labor market, with employers trying to sweeten the deal for employees to come back, but that may not last forever: federal unemployment benefits are set to expire in September and work search requirements have been reinstated for Connecticut.

Connecticut was already one of the slowest growing state economies in the country before the pandemic and research by economist Donald Klepper-Smith shows that Connecticut’s post-recession job recovery has slowed over the past four recessions.

A presentation by the Connecticut Center for Economic Analysis at UConn noted that Connecticut’s economic future is volatile, saying the American Rescue Plan may bolster Connecticut’s outlook temporarily, but the plan to use federal relief funds to plug budget gaps rather than stimulate the economy may cause problems down the road in the form of lower employment and lower tax revenue.

In the long-run, Connecticut’s underlying economy will likely continue to stagnate due to structural challenges built into Connecticut’s economy, according to Director of CCEA Fred Carstensen, PhD.

In his Green Sheet forecast on economic growth, UConn Professor of Economics Steven P. Lanza projects the job recovery will surge briefly before returning to a more moderate pace.

One big factor is fear of a resurgence of the COVID pandemic from the Delta Variant.

“The economy’s rebound in 2021-Q2 traces to the widespread distribution of COVID vaccines, the reopening of brick and mortar businesses, and the continued flow of federal relief dollars,” Lanza wrote.

“But the risks to the forecast are substantial. A significant minority of the population remains hostile to vaccines, keeping the goal of ‘herd immunity’ out of reach,” Lanza continued. “The now-dominant delta variant of the virus poses a renewed threat, even to those inoculated against the virus. And the feds are tightening the spigot on pandemic support.”