**This is the third article in our series on the eviction moratorium. Read the first and second installments by following the links**

Jennifer owns a multi-family house in Bristol in which she lives on the second-floor apartment and rents out the bottom and top floor apartments. In June of 2019, she rented the top floor to Crystal, a woman with three children, because she felt bad for them – the father and husband was in jail, Crystal was in a program to help her with housing and she had no place else to go.

By September of 2019, Crystal stopped paying rent and by November, unbeknownst to Jennifer, Crystal’s husband had been released from jail and was now living on the property as well – a fact that she didn’t learn until January of 2020 because she is often at work and away from the house.

Jennifer tried to work with Crystal when she first stopped paying rent. “I was trying to give her a chance, I was still trying to be kind and give her a chance to start paying,” Jennifer said, who has asked to remain anonymous due to her job and is therefore using a pseudonym.

By December of 2019, Jennifer had sent Crystal a typed letter, giving her one month to vacate the apartment and remove an unregistered vehicle that was parked on the property.

After she learned of the husband’s presence in the house in January of 2020 Jennifer sent a second letter, telling the couple that they had to be off the property by February 28, 2020 and demanding $3,540 in back rent. That is when the threats began.

According to Jennifer, the husband threatened the downstairs neighbor with bodily harm and Jennifer was forced to install security cameras and sensor lights.

“We were terrified,” Jennifer said. “He started vandalizing my property, he threatened the neighbor downstairs. The kids didn’t like the neighbor downstairs because she would tell me what happened when I wasn’t there. They took firecrackers and pelted them through her windows.”

In March of 2020, Jennifer filed with the court system to formally evict Crystal and her husband for nonpayment of rent. According to a statement Jennifer submitted to the court, she had another family lined up to move in and needed Crystal and her husband out.

“I can’t afford to have them stay here,” Jennifer wrote in a reply to defense. “It’s draining my finances, I am doing this all on my own, just me taking care of myself and my daughters, this is a business not a charity.”

According to court documents, the eviction was moving forward until the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the court system was shut down and both the federal government and Gov. Ned Lamont issued a moratorium on evictions.

Jennifer’s case remained in limbo for the nearly eight months until the courts reopened and a judge issued an eviction order in late October of 2020. By that time, Crystal owed over $15,000 in rent and Jennifer had endured a long period of stress and anxiety over what was happening in her home while paying a mortgage on the property.

“It was horrible,” Jennifer said, adding that her school-aged daughter also suffers from anxiety.

“I called the mayor’s office, I called the police department, I wrote a letter to [Senator] Blumenthal and to the governor,” Jennifer said. “I think those are the things that actually helped me get them off of my property.”

Because Jennifer had filed for eviction prior to the pandemic, she was not as directly affected by the moratorium as some other rental property owners.

The moratorium still allowed eviction of those who stopped paying rent before the state of emergency was declared and the eviction of tenants who were a “serious nuisance.” But closure of the court system created a de-facto moratorium for half a year, allowing problem tenants to remain in place and pay nothing during that time.

And because the tenants have been evicted, Jennifer is unable to receive any compensation through the UniteCT program, which uses federal COVID-relief funds to help tenants pay back rent to landlords.

“Why can’t the government pay us and then have the tenants pay them back?” Jennifer said. “At the end of the day, no one could go to Walmart and get an I.O.U. Why do landlords have to take an I.O.U.?”

“For landlords like myself who have to live on the property and have to live in fear every day, it’s just not fair,” Jennifer said. “As far as I see, Connecticut is not for landlords, they’re for the tenant.”

Jennifer said that following her experience with Crystal, she avoided renting out the apartment until the end of the moratorium because she didn’t want to be stuck again with a tenant who refused to pay.

And, according to some larger property owners and landlord advocates, the effects of the moratorium combined with recent legislation passed by the General Assembly could become a bigger problem for both landlords and tenants in the future.

Small rental property owners more vulnerable

According to her interview and documents submitted to the court system, Jennifer didn’t do a background check on Crystal. Rather she relied on statements by social workers and her empathy for a single mother facing hardship.

“I accepted Crystal’s application on the merits of the social worker at CHR,” the court document says. “I did not do a background check, when I took her as a renter, I took her without judgement because I figured she was a single mom like myself and needed a break in life.”

Robert De Cosmo, president of the Connecticut Property Owners Alliance and manager of Tenant Tracks, a background checking company for landlords, says that is one of the traps that small and new landlords fall into that can cause them financial damages in the long run.

“Many tenants have multiple evictions and they just know how to go from one owner to another owner,” De Cosmo says. “Most landlords are not what they’re stereotyped to be. They’re kind of gullible and they want to believe other people’s stories and believe that someone is really trying to get better and move them in.”

“Landlords do not pay mortgages with vacant units, so they don’t look to evict people, they don’t look to deny applications, they look to always fill their vacancies and that’s part of their problem,” De Cosmo said.

Roughly 35 percent of Connecticut’s 1.37 million households rent in Connecticut, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, a number that has slowly been rising since 2009. That means approximately 379,500 households – whether they be individuals or families – rent an apartment or house in the state.

In 2019, there were 20,000 evictions in Connecticut, according to the Connecticut Fair Housing Center, which noted that four of Connecticut’s cities had among the highest eviction rates in the country, with Waterbury topping out in the state with a 6.1 percent eviction rate in 2016.

Overall, based on the number of renting households in Connecticut, roughly 5.2 percent of renters are evicted in a normal year like 2019.

De Cosmo says that number has been trending downward over time, but the persistence of evictions is due, he says, to repeat offenders who “know how to go out and tell a nice story to get into someone’s apartment.”

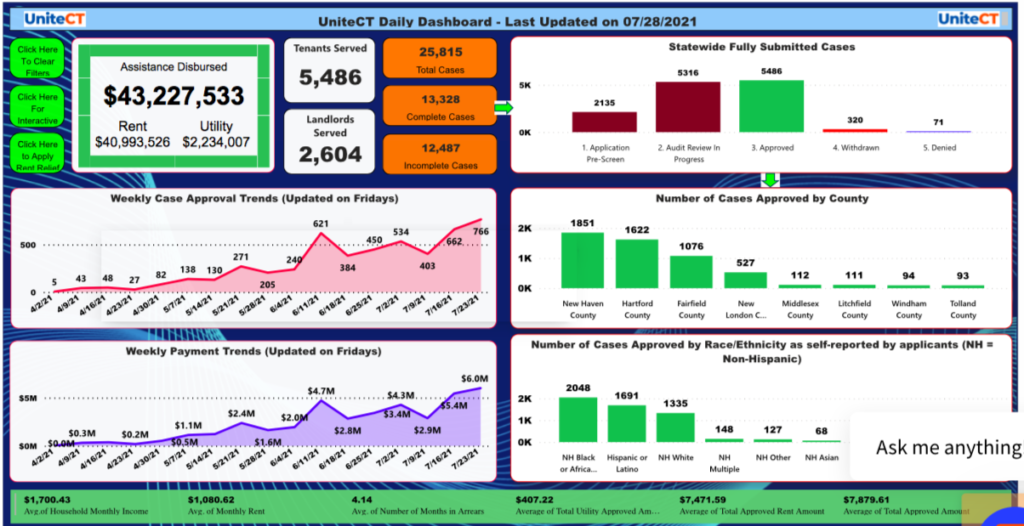

With the end of the moratorium and Connecticut’s court system facing a backlog of cases built up over the course of the pandemic, Gov. Ned Lamont created UniteCT as a means to get federal COVID-relief money to both tenants and landlords and stave off a potential surge in evictions.

Lamont also issued an executive order requiring landlords to first seek UniteCT funding before evicting for nonpayment of rent. Nevertheless, housing advocates have expressed concern that the program is off to a slow start, with $43.2 million being distributed out of $235 million received from the federal government.

The smaller landlords are going to lose, they’re going to lose their properties, they’re going to sell and the only people who have the money are the bigger property managers, the bigger guys, that were able to hold on through this and those are the people who are going to buy more and more properties.

David Candelora, Prime Management, LLC

In a nationwide analysis published by the New York Times, Sema K. Sgaier and Aaron Dibner-Dunlap of Surgo Ventures, a nonprofit based in Washington D.C. , estimated that between 10 percent and 13 percent of renters in Connecticut counties were behind on rent by upwards of $5,369, depending on the county.

The authors wrote that while distribution of the federal funds is “laudable,” the “rollout is too slow, too few renters are eligible, and the application process is too complicated.”

“As a result, funds are reaching only a small fraction of those who need them most,” Sgaier and Dibner-Dunlap wrote.

However, by taking the funds landlords agree not to evict the tenant for the duration they are in the program, which may not sit well with some rental property owners who feel they were taken advantage of during the pandemic.

Secondly, some property owners who have applied for the program say they are having difficulty getting the tenants to complete the application process.

“Those funds were designed for people who were impacted by COVID, whereas there’s a whole subset of the tenant population that never lost their social security disability, never stopped receiving Section 8 benefits, never lost their employment, simply stopped paying rent to take advantage of the moratorium,” De Cosmo said.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the eviction moratorium were felt more keenly by small rental property owners like Jennifer and Alvin Blount – whose story was featured in the first installment of this series — whereas larger landlords were able to better withstand the financial impact.

And that may not bode well for the future of rental property ownership in Connecticut.

David Candelora who manages 300 rental units in the New Haven area says that as small, local landlords who experienced losses may also face foreclosure or try to sell their properties, allowing the rental units to be acquired by larger, out-of-state landlords.

“There’s so many people out there that are mom & pops, that bought a two-family house and can only afford the house when someone else is paying a portion of their mortgage,” Candelora says. “The smaller landlords are going to lose, they’re going to lose their properties, they’re going to sell and the only people who have the money are the bigger property managers, the bigger guys, that were able to hold on through this and those are the people who are going to buy more and more properties.”

“This [the moratorium] was intended to help and to protect the poor but it destroyed the middle class and the lower middle class and it’s going to give all of those assets to people who are sitting on the sidelines with money,” David Candelora said.

Landlords concerned over legislative actions

Jennifer didn’t do an extensive background check on her tenant until it was too late.

According to a court document submitted by Jennifer, after she did a background check she found “multiple evictions, mug shots and convictions.”

“If I did my due diligence there would be no possible way that I would of allowed Crystal to move into my apartment,” Jennifer wrote. “I have been more than amicable, understanding and patient with this situation.”

During the 2021 legislative session, lawmakers passed the “clean slate bill,” which will erase certain criminal records for misdemeanor and low-level felonies from an individual’s record if they don’t re-offend for a period of seven years.

Advocates praised the legislation, saying that someone who has managed to turn their life around and not reoffend for such a long period of time should not have the weight of their past convictions hanging over their heads, harming their prospects for employment and housing.

Rental property owners, however, worry this may ultimately hamstring them when it comes to renting out apartments. Typically, a professional rental property owner will run a criminal background check on a tenant, look for prior evictions, work history, income verification and a credit check.

But the erasure of past criminal histories may make landlords more cautious in selecting a tenant; rather than decreasing discrimination in housing, the law may have the opposite effect, says David Haberfeld, a Bristol-based landlord whose Facebook post of damage done to his rental unit by a tenant went viral and spurred multiple television news stories.

“The problem here is that if you take away my ability to screen your record and you take away my ability to give someone a second chance because eviction is so expensive for landlords, what am I going to choose a tenant based on?” Haberfeld said. “How am I going to pick one applicant over another?”

“I’m going to have to turn people down based on my own personal preferences,” Haberfeld said. “That’s not what Democrats actually want.”

These protections they’ve put into the system hurt the tenant in a negative way, they force owners to raise rent to recoup losses that are sustained by these protections that are very, very short sighted. Very well intended but completely misguided.

Robert De Cosmo, President of the Connecticut Property Owners Alliance

De Cosmo, who runs a tenant background check company, says that thorough background checks are essential to ensuring a landlord selects a good tenant.

“I just ran a report and the guy had 16 convictions,” De Cosmo said. “Under their guidelines, I could show you that he has zero. I have a career criminal who for the last five years hasn’t been arrested because it’s always about nuisance stuff; disorderly conduct, breach of peace, threatening, low level assault, DUI.”

“You put someone like that on a property, that’s a nuisance tenant, and if you don’t know who you’re dealing with you’re going to lose two good tenants who live in that building by the time you evict that one bad one,” De Cosmo said.

They were also critical of legislation passed this year that provides federal COVID-relief money to provide attorneys for people facing eviction. Although the bill only appears to provide counsel for two years, advocates are hoping the program will become permanent through state funding.

“I cannot think of anything that hurts tenants more than that misguided legislation that makes no sense,” Haberfeld said. “These are always open and shut cases. There’s almost never any cases with extenuating circumstances, it’s always you didn’t pay, you’re selling drugs or you’re a serious nuisance of some kind.”

“It’s going to hurt tenants because landlords can’t take a chance on anyone anymore,” Haberfeld said. “If you had an eviction on your record 5 years ago and since then you’ve gotten a better job, you straightened out and you’re doing better for yourself, still no landlord is going to take you. We can’t take the risk. We’re going to wait for the next tenant.”

De Cosmo hopes that in the future the legislature will work more collaboratively with landlords, including conducting a state study on evictions in Connecticut.

“Simply put, states that have a quick eviction process and do not extend over and over again extra time delays for tenants have much more affordable housing, far less blight and less homelessness,” De Cosmo said.

“These protections they’ve put into the system hurt the tenant in a negative way, they force owners to raise rent to recoup losses that are sustained by these protections that are very, very short sighted,” De Cosmo says. “Very well intended but completely misguided.”