During a press conference at a Stratford train station announcing his $10 billion plan to speed up the New Haven Line, Gov. Ned Lamont was asked by a reporter about the highway use tax – a tax placed on large trucks that was passed during the 2021 legislative session – and Lamont was quick to emphasize that it was not a “tax” but rather a “fee.”

On June 7, during another press conference, Hartford Courant Reporter Chris Keating also asked about the highway use tax to which Lamont responded, “highway user fee.” When Paul Hughes from the Waterbury Republican-American pointed out that Lamont’s own budget referred to it as a tax, Lamont turned to his budget director and said, “Work on that, will ya?”

Over the course of his administration, Lamont has sought to distance himself from both his predecessor and some fellow Democrats by avoiding major tax increases on income and investment earnings, but he has also waged a public perception battle over several initiatives he has championed.

In an effort to paint himself as a Democrat who has stood against tax increases, Lamont has often tried to replace the T-word — “tax” — with the F-word — “fee” — as he tries to break Connecticut’s reputation as a high-tax state and as residents have grown vocal over calls for new taxes in a variety of forms.

Indeed, the Lamont administration has been beset with poor reception over several T-words and often the language – bouncing back and forth and changing with the political winds – can become confusing even for the governor.

Lamont’s early reversal of his campaign promise not to toll cars on Connecticut’s highways was met with intense public and political pushback, with opponents labeling tolls (another T-word) as a tax on drivers.

“I know this idea of tolling just sounds like one more damn tax I’m gonna have to pay,” Lamont said during his 2019 State of the State speech.

By November of that year the Lamont administration sought to quash the word “tolls” and replace it with the term “user fees,” when it released the CT2030 plan.

The plan posted online (which has since disappeared) only used the term “tolls” once, when indicating that there would be no toll booths on Connecticut’s highways. Otherwise, every reference to tolling was replaced with “fees.”

At the time, the No Tolls CT movement had peaked in its statewide opposition to Lamont’s various and changing tolling plans. But it was a little late for a change in the language; “No Tolls” had become a rallying cry and “No User Fees” just didn’t have the same ring to it.

In his first budget, Lamont proposed and eventually passed a 10-cent tax on single-use plastic grocery bags.

The 10-cent charge came under a variety of terms: it was listed as “surcharge” under “Miscellaneous Taxes” in the budget, but the Lamont administration called it a fee and used the terms interchangeably in the budget.

“To combat the ill-effects of human plastic consumption, this budget proposes a fee on non-compostable plastic bags at ten cents per plastic bag,” the governor’s budget proposal read. “Out-year revenue estimates assume declining usage of such bags due to the proposed new tax.”

More recently, another T-word hounded the governor: TCI, or the Transportation and Climate Initiative.

According to proponents the TCI program is a regional “cap and invest” program for fuel wholesalers and distributors in order to reduce transportation emissions. For opponents it was a “tax” on gasoline because the program would raise the price of fuel at the pump and send the money to the government.

Early in 2020, Lamont pushed back against the TCI program, likening it “raising the gas tax,” during a radio interview with WNPR and reprinted in a Connecticut Post article titled “Lamont backs away from clean-air gas tax.”

However, after tolling proposals were shelved and Lamont signed on to the final memorandum of understanding with TCI, the tax word was also shelved in favor of the word fee.

When asked whether or not he would push for a Special Session to approve the TCI pact, Lamont said “I think it’s a small fee on petroleum wholesalers,” during a June 10, 2021 press conference.

But the governor had also called it a “small carbon tax,” during a press conference on March 17, 2021 in Middletown, touting the benefits of TCI, according to the Republican-American.

His comment was immediately repudiated by Sen. Christine Cohen, D-Guilford, and chair of legislature’s the Environment Committee, and seized upon by opponents of TCI.

By the end of session, Senate President Pro-Tem Martin Looney, said TCI was a “regressive tax,” according to CT Mirror, and commented it would “cause an increase in the gasoline tax to low-income people,” according to CTNewsJunkie.

Are They Taxes or Fees?

The hodge-podge of terms used to describe the various proposals and costs imposed on Connecticut residents obscure definitions, which can be politically advantageous for either side of the debate.

In a high-tax state like Connecticut, which has seen three major tax increases lead to nothing but more government spending and more budget deficits, any additional money going out of people’s pockets and into state government is quickly and easily labeled as a tax.

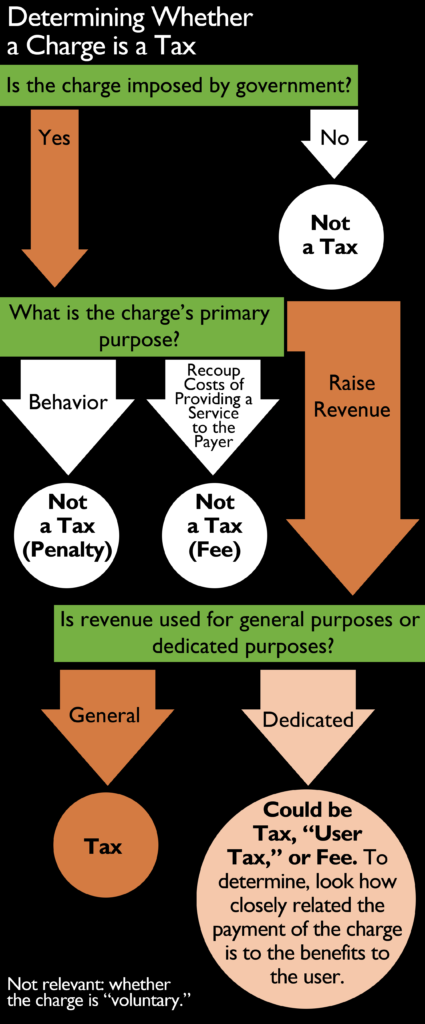

The Tax Foundation, in a 2013 paper that dissected the legal differences between a tax and a fee, noted that the difference between the two depended on the purpose of the charge, dividing them into three categories – taxes, fees and penalties – with the three occasionally overlapping and creating their own subset of tax terms.

According to study author Joseph Henchman, a tax is for the purpose of raising revenue, while a fee is to recoup costs for a service provided and a penalty is for the purpose penalizing or regulating behavior.

But there are also taxes known as “Pigouvian taxes,” which are meant to discourage a particular behavior but also raise revenue – think cigarette taxes – and there are “user taxes,” which are deposited into a special fund that isn’t the General Fund – think Connecticut’s Special Transportation Fund — for the purpose of raising revenue.

“A charge is not a fee simply because official decide to call it that,” Henchman wrote. “If that was the only requirement, legislators would eagerly re-label every tax into a fee.”

According to the Tax Foundation report, Connecticut’s Supreme Court has not ruled on the distinction between a tax and a fee, but a lower court – in the case of Gagne v. City of Hartford – considered a three-part test on whether something is a tax or a fee.

According to the 1994 decision, to determine whether or not something is a tax or a fee depends on whether or not it is voluntary or mandatory; whether the fee is for services that others do not benefit from and whether the charges raise revenue or compensate for government expenses.

But rarely are fees added to Connecticut that don’t have something to do with raising revenue and bridging budget deficits. While a new proposed fee may have some lofty stated goal, the byproduct is revenue, and the terms get intermingled very quickly.

In the case Connecticut’s new highway use tax, the revenue will be deposited into the Special Transportation Fund, amounting to roughly $90 million per year. How the money is spent from there depends.

While the highway use tax was touted as providing revenue to recoup the cost of damage to Connecticut’s roads from big-rig trucks, Gov. Lamont cited the highway use tax as enabling Connecticut to get federal loans to speed up the New Haven Rail Line, which will be of little use to truckers.

In the case of tolls, the money would have also gone into the STF for infrastructure funding but included in the enabling legislation was a list of projects that included rail and bus operations, so certainly not all of the toll revenue would have been used for the road on which they were collected.

The plastic bag tax was meant to discourage use of single-use plastic bags – and it did, with revenue falling far short of predictions – but ultimately it was a revenue raising provision going into the General Fund enacted during a budget cycle that faced another $3.7 billion deficit.

For the Transportation and Climate Initiative, half of the revenue raised from the auctioning of emission credits would go toward climate justice initiatives aimed at reducing the impact of emissions in cities under the advisement of an equity board, while the other half was outlined as paying for public transportation costs and electric vehicle infrastructure.

During a press conference in New Britain, Gov. Lamont touted the TCI program as a way to continue offering free bus service on the weekends, while Sen. Will Haskell, D-Wilton, touted the TCI program as integral to expanding electric vehicle ownership.

What category those various proposals or laws fall into may be in the eye of the beholder, or they could be both a tax and a fee, as the various goals of the proposals bump up against a legal definition that, in the end, may not actually matter.

Does it Matter?

In the end, the money goes from Connecticut residents or truckers or businesses to the government, so does the name or method really matter?

Politically, the answer may be Yes.

Lamont has made a name for himself in Connecticut and nationally opposing major tax increases pushed by the progressive wing of his own party, namely increased income taxes on the wealthy through a stealthily titled “consumption tax,” a “surcharge” on investment earnings and a “mansion tax” on homes that often would not qualify as a “mansion.”

Professor Gary Rose of Sacred Heart University says Lamont’s opposition to those major tax increases and his attempts to “camouflage” more limited taxes like the highway use tax or plastic bag tax as a “fee” has paid off.

“The voters, at least those that are polled, don’t feel that he’s a run of mill tax-and-spend liberal, when in fact the governor is perhaps little more oriented towards that than people think,” Rose said in an interview.

“There’s no question at all that a fee and a tax are the same thing,” Rose said. “It’s a form of taxation but it’s under the radar. They’re simply using different terminology for what, for all intents and purposes, is taxation.”

“I think he knew he had public opinion on his side in the budget process and the way he’s handled the pandemic too certainly shows his approval ratings are high, so I think he’s wanted to keep those approval rating high as the budget worked its way through the legislature by keeping the word ‘tax’ out of the picture,” Rose said.

Republicans, on the other hand, have seized upon Connecticut’s tax-weariness as a way to oppose new revenue sources, campaigning against the highway use tax as a tax on food, arguing it would raise the cost of transporting necessities to the grocery store, and labeling the TCI program as a gasoline tax.

Republican strategist Liz Kurantowicz says the problem with playing word-games is that it erodes trust in government and elected leaders.

“Generally speaking there is a trust deficit between the residents of this state and the one-party controlling state government, and its rooted in these sorts of linguistic shell games,” Kurantowicz said. “When the state government is taking your hard earned money to spend as they see fit, it’s a tax.”

As of 2019, Connecticut had 344 different revenue sources, many of them taxes, but many more of them fees for licensing and permits, and most of them go into the General Fund, according to Yankee Institute’s latest listing of Connecticut’s revenue sources. Of those revenue sources, 200 account for only .22 percent of the budget and are generally fees related to licensing for business or recreational activities.

Since many of those fees only affect a small subset of the population, they generally go unnoticed but for the occasional grumble of an individual or business that is affected by them. Few people hear the lament of lobster divers who have to pay a fee to set more than 10 traps, which brought in $14,460 in 2019.

However, bigger ticket revenue sources debated in the General Assembly, like the highway use tax for truckers, tolls, the plastic bag tax or TCI affect nearly everyone either directly or indirectly and, despite whatever linguistic gymnastics attempted by lawmakers, the public appears quick to take up the “it’s a tax” mantra.

“Residents of this state are on to the governor’s equivocation and that’s why he failed to accomplish his major tax initiatives in the last session despite having a super-majority in the Senate and a strong majority in the House,” Kurantowicz said. “You can’t govern without trust and you don’t gain trust when you think you’re smarter than the people paying the bill.”

“The Republicans are more obviously frank with the voters on this issue and calling it what it is,” Rose said. “But the question is who’s hearing that and how is it being reported?”

**Meghan Portfolio contributed to this article**

Fred Carstensen

June 30, 2021 @ 1:25 pm

This piece really gets into the weeds, but manages to ignore two critical points that ought to frame the discussion.

1) the really big issue is that connecticut has the worst performing state ecnomy in the nation–it never recovered after the great recession. even in February 2020, connecticut had not recovery in either employment or real output to its previous peaks more than a decade ago. in contrast, our neighboring states had all enjoyed robust recoveries in both jobs and real output. Critically, while virtually all other states have become more integrated with the national economy and thus have economic cycles more synchronized with national growth, Connecticut disconnected. It no longer appears to be part of the national economy–indeed, while the national economy grew more than 18% in the last decade, connecticut’s economy shrank about 3%. it is thus hugely important to put this discussion in the context of the failing economy.

2) The second issue is that Connecticut’s infrastructure–especially roads, bridges, and commuter rail–are in poor condition and clearly undermine the state’s competitive position. Given where connecticut is (see above comment); restoring competitive health is thus absolutely central to restoring fiscal health. There is nothing in this commentary that acknowledges the broad challenge of economic growth for a failing state economy or speaks to how to address the critical need to restore our infrastructure, without which achieving that economic restoration is unlikely.

Thad M Stewart

July 1, 2021 @ 3:07 pm

Great point Fred. But no matter how they try you cannot tax your way to prosperity. Cuts need to be made across the board, and the unions are goint to have to take cuts along with the gluttonous gubment of Connecticut.

John C Miller Jr

July 4, 2021 @ 2:11 pm

When i went to work in the trucking industry four decades ago for a connecticut based carrier, this was known as the ton-mile tax before canada came into the fold and it became the international fuel tax agreement. we used to undergo an annual fuel tax audit by the state of connecticut to make sure we were paying the ton-mile tax that was owed to the state. this is just piling on and we already know that a great deal of these taxes were diverted from the stf to the general fund.