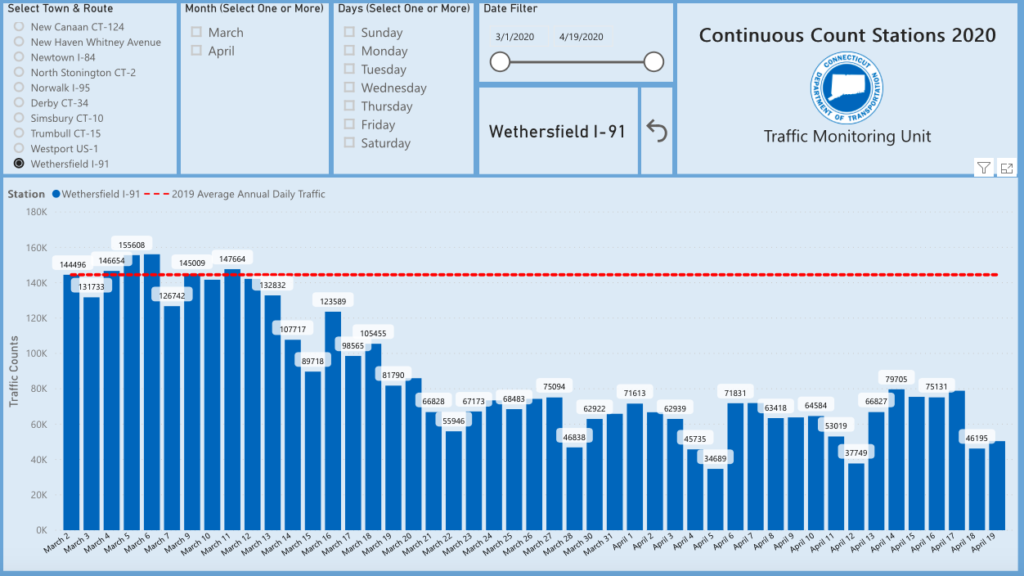

Traffic numbers from the Connecticut Department of Transportation show a steep drop-off in people traveling on Connecticut’s highways in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of nonessential businesses by the governor.

The number of vehicles traveling along I-84, I-91 and I-95 at particular points dropped by as much as 50 percent.

On I-84 in Newtown, for instance, the number of vehicles dropped from an average of roughly 78,000 in 2019 to 39,043 on Thursday, April 16 — a 50 percent decline. Many days saw significantly fewer cars and trucks.

I-95 in Branford saw the number of vehicles drop 49 percent, from a 2019 average of roughly 86,000 per day to 42,291, as of April 16. In Norwalk, the drop was 42 percent.

I-91 in Wethersfield saw a 49 percent decline in vehicles

At the same time, gasoline prices have reached the lowest point in recent history, the result of an oil price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia.

None of this bodes well for Connecticut’s Special Transportation Fund, which relies on the state’s gasoline tax and oil companies gross receipts tax as two of its largest revenue sources.

While the state gasoline tax of 25 cents per gallon is a set rate, fewer people driving means declining gasoline sales. A report from OPIS Pricing and Marketing Analysis for Oil, Fuel & Energy showed retail station sales were down 46.6 percent for the week ending March 28.

Michael Fox, executive director of the Greenwich-based Gasoline & Automotive Service Dealers of America, Inc., says gas stations are seeing a steep drop-offs in sales.

“My members are talking about numbers between 40 and 60 percent lower in sales,” Fox said. “There’s just no traffic or volume out there.”

My members are talking about numbers between 40 and 60 percent lower in sales. There’s just no traffic or volume out there.

Michael Fox, Executive Director of the Gasoline & Automotive Service Dealers of America

Fox said typically high-volume stations, in particular, are seeing steep declines in sales, noting that a typical high-volume station sells anywhere between 100,000 and 150,000 gallons of gasoline per week.

Fox says the STF will take “a double hit,” because the price of gasoline and oil has plummeted, impacting the fund’s third-largest revenue source: the petroleum gross receipts tax.

In FY 2019, the STF took in $509.7 million from the motor fuels tax and $313 million from the oil companies tax, according to the state’s Open Budget website.

This fiscal year – which ends June 30 – the state has taken in $303.5 million in the gasoline tax and $153.1 million from the oil companies tax.

During the 2019 fiscal year, the state took in an average of $31.2 million per month in gasoline tax revenue, according to the CT Data website, although revenue figures for all months were not yet available.

A percentage of the state sales tax is also deposited into the STF, constituting the second-largest revenue source for the STF. Indications are Connecticut could see lower sales tax revenue as many businesses are closed and residents are spending less

The STF started the year with a balance of $320 million and a projected surplus of $13 million, but, according to recent budget projections from the Office of Fiscal Analysis and the Office of Policy and Management, that balance is already declining significantly due to oil prices and reduced commuter travel.

The Office of Policy and Management is estimating a revenue loss of $102 million, resulting from lower gasoline sales, sales tax revenue and oil company gross receipts, leaving the fund’s balance at $184.3 million.

The Motor Fuels Tax has been revised downward by $26.5 million due to significant declines in consumption resulting from increased telecommuting and social distancing orders which we assume will continue through the month of May.

Office of Policy and Management Secretary Melissa McCaw

“The Motor Fuels Tax has been revised downward by $26.5 million due to significant declines in consumption resulting from increased telecommuting and social distancing orders which we assume will continue through the month of May,” OPM Secretary Melissa McCaw wrote in an April 20 report to State Comptroller Kevin Lembo.

“The Oil Companies Tax has been revised downward by $18.0 million as a result of continued declines in the price of oil. The Sales and Use Tax has been revised downward by $26.3 million, consistent with revisions made in the General Fund,” McCaw wrote.

The STF had been on track to have a cumulative balance of $638.9 million by 2024, according to the OFA. However, according to the governor’s office, after 2024 debt service payments for Connecticut’s past borrowing would begin to outpace revenue.

The future of the STF has already been the subject of a multi-year fight regarding tolls on Connecticut’s highways.

Both Gov. Dannel Malloy and Gov. Ned Lamont argued tolls were necessary to support the STF because gasoline tax revenue had flattened, and debt service costs were projected to rise, but the public backlash to the tolling proposals eventually killed the government’s push for tolls in early 2020.

But the lower gasoline sales and prices are not the only problem for the state’s transportation fund.

The pandemic and social distancing measures put into place have led to decreased usage of public transportation, which means much lower ticket sales for trains and buses.

Subsidies for trains and buses constitute one of the largest payouts for the state’s transportation fund, but without ticket sales those subsidies will likely grow. The New Haven Line, for instance, took in $356.3 million in ticket sales during the 2019 fiscal year, according to numbers provided by DOT.

“The decrease in ridership is a reflection of the fact that our customers are continuing to follow the advice of health professionals to keep themselves and others safe,” said CTDOT Public Transportation Bureau Chief Richard Andreski in a March 27 press release.

Although the Connecticut Department of Motor Vehicles has closed its doors to the public, many services remain available online. License renewals have been extended during the shutdown.

DMV and registration fees are also a significant source of revenue for the STF, but, presumably, license renewal fees will start flowing again when the offices reopen, making it only a temporary loss. OPM projects that $20 million of DMV revenue will be shifted to the 2021 fiscal year.

Although revenues will surely decrease, expenses most likely won’t — at least not nearly enough to make up for the loss.

Payroll is the biggest cost for state agencies and many DOT employees are considered essential and are working on the states roads and bridges. Those employees deemed nonessential have been working from home when possible.

A DOT worker who works on Connecticut’s bridges, and agreed to offer comment on condition of anonymity, says even though he’s considered an essential employee, he was told to stay home for a week with pay.

“Half my guys are staying home this week, and I’m doing it next week,” he said in an interview. “If I’m an essential employee, why am I home? A week off isn’t going to change a damn thing. I’d rather be at work than sitting at home.”

Connecticut is currently sitting on a reserve fund of roughly $2.5 billion.

Early estimates project Connecticut may face a $500 million deficit this year and a $1.5 billion deficit next year as a result from the shutdown and economic downturn, although those numbers will likely depend on how long the pandemic and recession continues.

David Chu

April 22, 2020 @ 12:16 pm

The oil companies tax, a.k.a. the gross earnings tax (GET), decline of $18 million estimated by the state is in line with our calculations. We are estimating that current state collections of the GET are off by $500,000 per day compared to pre-crisis collections during Jan-Feb. That equals a loss in revenues of about $15 million for the 30-day period March 20-April 20. Our estimate includes both a loss due to the decline in oil prices, resulting in a GET reduction in revenue of about 10 cents a gallon, plus a conservatively estimated 40% decline in volume.