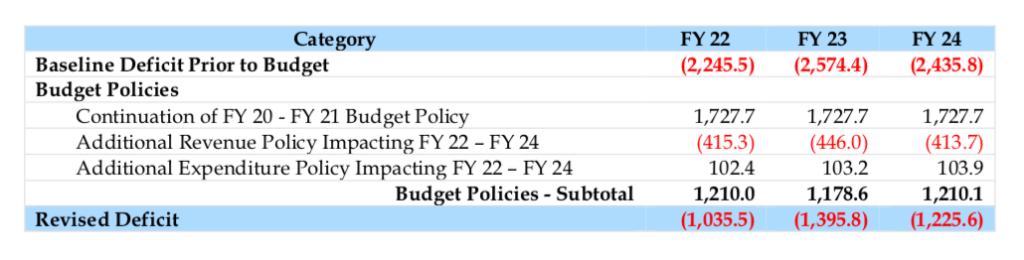

Despite increasing General Fund revenue by $2.52 billion over the next two years, Connecticut will still face billion-dollar budget deficits from 2022 through 2024, according to a budget report released by the Office of Fiscal Analysis.

“The General Fund is projected to be in deficit by over $1 billion per fiscal year starting in FY 22 and lasting through FY 24,” the report said. “Nonetheless, policies enacted in the recent budget will improve projected out year deficits, as compared to the baseline estimates, by approximately $1.2 billion per fiscal year.”

The budget passed during the 2019 legislative session raised tax rates on digital downloads and prepared meals at restaurants, kept a corporate tax from sunsetting, reduced a personal income tax credit for pass through entities, continued to tax hospitals and diverted vehicle sales tax revenue away from the Special Transportation Fund – among other things – to balance the budget.

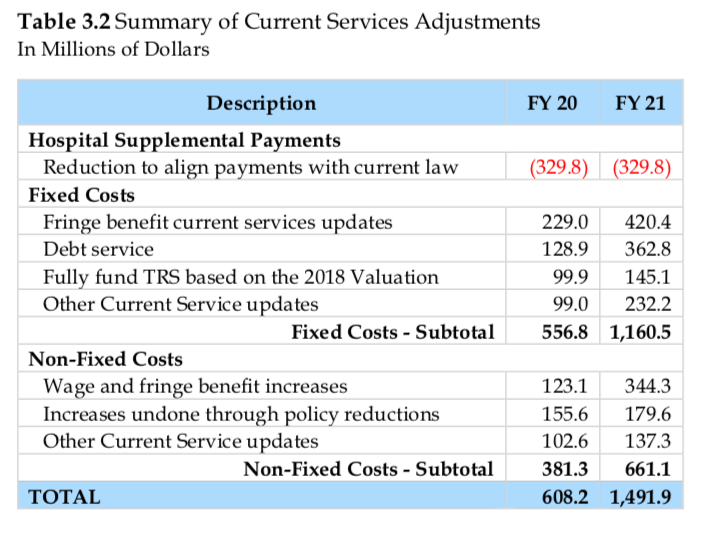

The report also notes that Connecticut’s fixed costs – debt service, Medicaid, pensions and retirement medical benefits – are expected to continue increasing by $550 million per year.

Gov. Ned Lamont achieved some pension savings through extending the payback period for state employee and teacher pension debt, lowering the yearly cost in the short-term but adding billions over the long-term in an effort to prevent pension costs from spiking.

Although Connecticut finished the year with a surplus, the state’s volatility cap transfers much of the surplus to Connecticut’s Rainy Day fund, which is now approaching record-levels of funding in case the country enters into another recession.

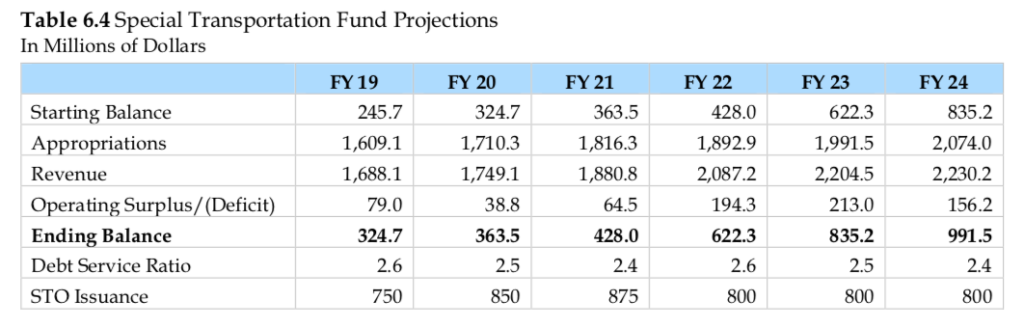

The state’s Special Transportation Fund is expected to maintain surpluses through 2024, despite the legislature diverting $178 million from transportation in order to balance the budget. Revenue to the STF is expected to grow from $1.7 billion in 2020 to $2.2 billion in 2024.

The Lamont administration, however, argues that growing debt service payments will leave the STF in deficit and have pushed for a plan to institute tolls on Connecticut’s highways.

Lamont’s tolling plan was met with stiff public and legislative resistance and the governor is expected to release a new transportation plan in the coming months that will rely less heavily on tolls and incorporate loans from the federal government.

But the prospect of continuing deficits in the out years leaves open the possibility for either more revenue increases in the form of taxes and fees, another diversion of revenue from the transportation fund or a possible reduction in the state employee workforce.

Under the 2017 SEBAC agreement negotiated by Gov. Dannel Malloy and passed narrowly by the General Assembly, state employees were granted layoff protection until 2021 along with pay increases totaling at least 11 percent.

But there may be a spike in the number of state employees retiring before 2022, when pension calculations for retirees’ annual cost of living adjustments will change.

Vehicle sales tax revenue to the STF is projected to return to its pre-set levels so that 100 percent of the revenue is put toward transportation as outlined in the 2017 budget agreement, but there are no guarantees the legislature will not divert the revenue again.

Although the 2019 budget was technically under the state’s Constitutional Spending Cap by $200,000, the legislature did engage in some tricky accounting by shifting $20 million for the Partnership for Connecticut and $5.1 million in start-up costs for the paid family and medical leave program off budget, essentially skirting around the spending cap.

The current numbers and projections reported by the OFA show a marked improvement in the projected deficits for 2022 through 2024, reducing the three-year deficits from $7.2 billion to $3.6 billion.

Connecticut has also seen an upward trend in revenue from the state’s income tax withholding, which is expected to grow by $347 million by 2021, according to OFA, but state spending continues to grow.

According to the report, the 2020 budget is 2.1 percent more than the 2019 budget and 2021 is 3.7 percent more than the 2020 budget.

A 2017 study by Pew Charitable Trusts showed Connecticut was consistently in the red, taking in 97 percent of revenue needed to cover expenses on average.

Prior deficits led to major tax increases in 2009, 2011 and 2015, along with concessions from state employee unions in 2011 and 2017.

Ralph DeMartino

October 23, 2019 @ 6:23 pm

We should have voted for the Constitutional

convention that would allow for recall of the Governor . Malloy , Lamont would not act the way they do as they would have been recalled from office . A number of states have it , it makes the politicians more responsive .

The economy has been going great the last two years ,we can’t expect that to continue ,need to cut expenses now .

brandon

October 24, 2019 @ 12:03 pm

Connecticut unions and leaders, you are leaving small business owners and professionals in my generation (cusp of generation X and millennial) no choice but to take our businesses to other states where a future is possible. Stop cannibalizing future generations for your own ever-growing waistlines.

CTEscapee

February 16, 2020 @ 10:45 am

11% Pay increases for state workers while the average in CT is 1-3% .?? And that’s for those who still have jobs. Also, lets replace the mass outflux of tax payers with welfare collecting ‘refugees’. Good idea. Get out now while you can.