It’s like a lesson in how to create a public-policy upheaval in Connecticut.

One small law firm of five attorneys based in Hartford has successfully created a public-policy rift between Gov. Ned Lamont’s administration and the entirety of the Connecticut legislature after Lamont vetoed a bipartisan bill that would have retroactively clarified state regulations regarding the restaurant wage tip credit.

The legislation was spurred by an on-going series of lawsuits filed by the Hayber, McKenna & Dinsmore law firm on behalf of restaurant employees against a number of restaurants in Connecticut, ranging from chains like Outback Steakhouse and Ruby Tuesday’s to more local restaurants like Brick & Wood in Fairfield, 85 Main in Prospect and Chips Family Restaurant with various locations throughout the state.

Hayber, McKenna & Dinsmore describes itself as an employee rights advocate that has “dedicated our practice to helping employees and their families who have suffered losses due to unfair employment practices.”

Since 2015, Hayber has filed 15 lawsuits alleging restaurants have improperly paid bartenders, waiters and waitresses below minimum wage for non-service work. The “tip-credit” allows a restaurant to pay a server 31 percent less than the state’s minimum wage for work in which the employee will receive gratuities.

The lawsuits are based on a disparity between Connecticut regulations and the state Department of Labor’s wage guidelines for restaurants which they published in 2015 and, until December of 2018, had posted on their website.

Six of those lawsuits were filed as class action suits involving numerous plaintiffs, which could have far-reaching financial implications for the restaurants.

In 2019 alone, six lawsuits — including three complaints filed as class action suits which are awaiting certification – have been filed against 99 Restaurants, Outback Steakhouse, Ruby Tuesdays, 85 Main, Brick & Wood and C&L Diners. Hayber, McKenna & Dinsmore is representing the plaintiffs in all the cases.

The onslaught of lawsuits spurred the legislature to pass a bill that would have retroactively codified Connecticut’s restaurant wage tip credit to match what the Connecticut Department of Labor had been telling restaurant owners for years. The legislation would have effectively killed the various lawsuits.

But Lamont’s veto has left lawmakers and restaurant owners scrambling for a viable solution during the summer months in an effort to curb legal action that threatens to shutter some Connecticut businesses with mounting legal fees and penalties.

The Evolution of Legal Action

According to state regulations, if a server performs “service duties” they can be paid below the state’s minimum wage, but if they perform “non-service duties” for which they do not receive a tip they must be paid the full minimum wage.

State regulation says servers’ time performing each should be “definitely segregated and so recorded” in order for the lower wage to be paid. If the time is not recorded and segregated than the regular minimum wage is to be paid.

What constitutes “non-service duties” is part of the legal issue: technically, a server can only be paid the lower rate for things like cleaning and resetting a table in their section. However, servers often help prepare the restaurant for serving customers by wrapping silverware, cutting fruit for drinks, or getting drink stations ready to serve.

Segregating and recording different wage rates for different short tasks among numerous servers over the course of the day at a restaurant presents numerous administrative and time-management hurdles for both restaurant owners and employees.

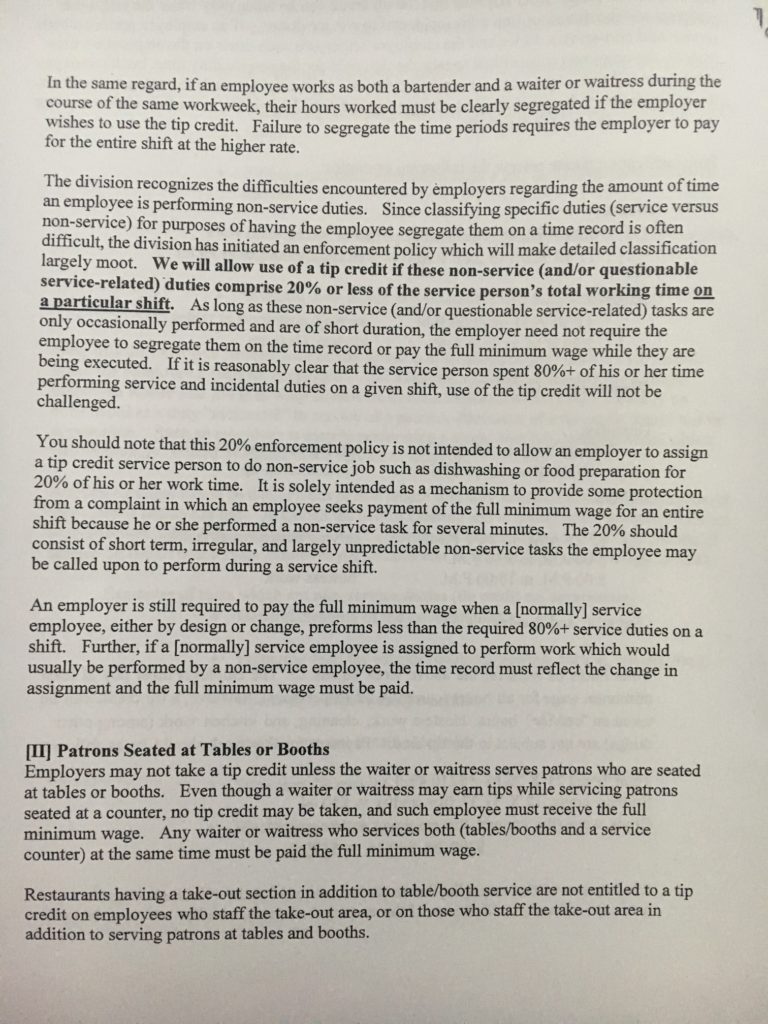

The Connecticut Department of Labor tried to ease the regulatory burden by issuing guidance in a 2015 publication by the Department of Labor’s Wage and Workplace Standards Division entitled “Basic Guide to Wage and Hour and Related Laws Regarding the Restaurant Industry.”

According to the DOL’s publication, “We will allow use of a tip credit if these non-service (and/or questionable service-related) duties comprise 20% or less of the service person’s total working time on a particular shift.”

The workbook notes that since segregating employee time by what work they perform is “difficult” the division “initiated an enforcement policy which will make detailed classification largely moot.”

The change brought Connecticut in line with the federal Department of Labor’s wage tip credit guidelines.

The workbook notes this protection does not allow a restaurant to assign non-service duties like dishwashing or food preparation to a service-employee but rather “to provide some protection from a complaint in which an employee seeks payment of the full minimum wage for an entire shift because he or she performed a non-service task for several minutes.”

However, the DOL’s attempt at making detailed classification “largely moot” had an unintended consequence: the crux of Hayber’s arguments against the various restaurants is predicated on the fact that the employers did not keep detailed accounting of time a server spent doing non-service work and did not obtain weekly signed statements from servers confirming they received service tips.

In a 2015 lawsuit against Vito’s by the Water — formerly located in Windsor — Hayber argued that former bartender Shaneque Stevens’ hours spent setting up the restaurant before opening and cleaning up after closure should have been segregated from her service work and received the full minimum wage.

According to “Plaintiff’s Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law” filed in 2017 against Vito’s the burden of proof rests on the employer to “come forward with evidence of the precise amount of work performed or with evidence to the negative reasonableness of the inference to be drawn from the employee’s evidence.”

The judge sided with the plaintiff, writing that “Vito’s failed to obtain weekly tip statements” required by state regulations and “did not segregate Stevens’ non-service work from her service work and thus was obliged to, but did not, pay the service hours at the full minimum fair wage.”

The plaintiff was awarded payment equal to twice the minimum wage for the estimated hours she was underpaid plus attorney fees, all of which totaled $54,766.47.

The award of legal fees to Hayber was decried as a “dangerous precedent” by John Kennelly, attorney for Vito’s, in an interview with the Connecticut Law Tribune. Kennelly said the ruling “means there is now an open season for every small restaurant business that does not have an entire legal department to protect them from the minutia of the state Department of Labor regulations.”

Richard Hayber of Hayber, McKenna & Dinsmore said the award of attorney fees allows workers who don’t have much money to be represented in court. “This is an important ruling for attorneys who take on wage cases for low-wage workers that they will be paid when they win,” Hayber told the Law Tribune.

Vito’s by the Water closed down shortly thereafter and in 2018 filed for bankruptcy in federal court, although it’s unknown if the bankruptcy filing was directly related to costs associated with the court case or the judgement.

But the judge’s 2017 ruling was used as precedent in other lawsuits Hayber filed on behalf of restaurant employees.

For instance, a suit filed in 2018 against C&L Diners which owns a Denny’s Restaurant in Westbrook and two 2019 suits against 99 Restaurants and 85 Main reference the Stevens decision in their initial complaint and use the same argument that was successful against Vito’s.

In the case against 85 Main, the complaint says servers were required to do “side-work” which included “general cleaning and stocking duties such as stocking all paper cups and straws, condiments, to go items, restocking and polishing all silverware, cleaning the potato station, the soda machine, butters, sweeping the server alley and other similar activities.”

The lawsuit contends the servers should have been paid full minimum wage for performing these duties because servers were not receiving tips during that time. According to the 2003 Guide for Restaurant Employers in Connecticut, the tip credit only applies if the server is maintaining their own “immediate service area.”

The lawsuits predicated on the Vito’s ruling had a chilling effect on Connecticut’s restaurant owners.

While a suit on behalf of one employee could cost a restaurant tens to hundreds of thousands in a judgement – including the restaurant owner’s attorney fees – the class action lawsuits threaten judgements in the hundreds of thousands to potentially millions.

In a press release, the Connecticut Restaurant Association said employers shouldn’t be punished for following the guidelines set forth by DOL unless they violated the 80/20 rule. “Class action lawsuits such as these threaten to put restaurant owners out-of-business, placing hundreds of jobs in jeopardy.”

The class action lawsuits can be especially damaging. Chips Family Restaurant, which has six locations in Connecticut, is facing a class action suit involving upwards of 200 employees. A judgement against the restaurant, in addition to legal fees for both the defendants and the plaintiffs, could be “a death sentence,” according to Scott Dolch, President of the Connecticut Restaurant Association.

Am I Safe? Connecticut’s Shifting Tip Credit Policies

“I have more and more people coming to me and asking, ‘am I safe?’ and the answer right now is you’re not,” said Dolch. “Everyone is potentially liable — all 8,000 restaurants in Connecticut — because they were following DOL’s guidelines.”

Part of the problem is that it appears the CT DOL changed its mind regarding the 80/20 rule. Previous iterations of the restaurant guide book in 2003 and 2014 did not include the 80/20 rule and stuck to the original wording of the state regulation.

The 2014 guidebook would have applied to the Vito’s case, which was filed before the 2015 guidebook changed DOL’s guidance. How a court might react to cases filed since CT DOL’s 2015 guidance is anyone’s guess.

But, it appears DOL has changed their mind again as the website removed reference to the 80/20 rule in December of 2018, reverting guidance to the original regulatory language.

After passing a $15 minimum wage – which was largely opposed by the restaurant industry – lawmakers from both sides of the aisle passed House Bill 5001 with an amendment to clarify Connecticut’s regulations to match federal regulations for the 80/20 rule – which, coincidentally, was just eliminated by the U.S. Department of Labor in response to an “explosion of litigation across the country” against restaurants, according to law firm Foley & Lardner LLP.

Foley & Lardner also wrote that many of the lawsuits nationally have hinged what constitutes non-service work, such as helping set up or close down the restaurant, despite the federal 80/20 rule.

“This has to be fixed legislatively,” Dolch said, “because we can’t wait three years for a change of regulation.”

The state legislature agreed, passing an amendment that retroactively set the 80/20 rule in statute during the final hours of session. The last-minute amendment left the bill ripe for the opposition to cry foul. State labor unions saw the legislation as an unfair attempt to get restaurants off the hook that flew in the face of government transparency.

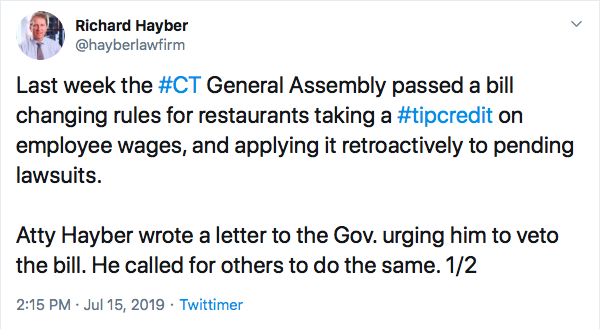

Richard Hayber tweeted that he sent a letter to Lamont urging him to veto the legislation. The governor issued his veto shortly after saying he wouldn’t veto any legislation passed during the session.

The veto angered both Democratic and Republican House and Senate leaders who threatened a veto-override but ultimately couldn’t come to agreement in both chambers. Lamont said he opposed the retroactive provision in the legislation.

Lamont’s veto was cheered by unions such as the SEIU 1199, which has sought to unionize restaurant workers in other states, and the Connecticut chapter of the AFL-CIO, which sees the lawsuits as a way to protect workers. Both organizations heavily backed Lamont in his 2018 race for governor.

In a statement, the Connecticut State Council for SEIU wrote “We support Ned Lamont for exercising the Executive’s veto power to stand up for working people. His recent rejection of a bill that was hastily passed without debate or public hearings at the General Assembly is a positive step to protect the rights of restaurant workers in Connecticut.”

The push by state labor unions to allow the lawsuits to move forward with Lamont’s veto was at odds with House Speaker Joe Aresimowicz, D-Berlin, who backed the legislation. Aresimowicz is an employee of AFSCME Council 4 – an affiliate of the AFL-CIO – but said the unions had no business inserting themselves in the debate.

Dolch says the notion that the tip credit fix was passed under cover of darkness is misleading, saying he worked with legislative leaders and the DOL on implementing this fix early in the 2019 legislative session.

“We’re not trying to change anything, just repeal a regulation which would then revert the state to the federal tip credit guidelines until DOL can develop a solid regulation,” Dolch said. “Meanwhile, restaurants can continue operating as they have been for years.”

Legislative leaders are reportedly close to a compromise which they hope Lamont will sign, but without a retroactive provision in the compromise, restaurants will still face potential lawsuits because there is a two-year “look back” window on state regulatory changes.

Dolch acknowledges that in every industry there are “bad actors” who should be dealt with legally. In Connecticut, the DOL’s Wage and Workplace Standards Division will investigate complaints against employers and seek restitution and penalties if those employers are found to be under-cutting Connecticut’s wage laws.

But Dolch says that shifting regulatory guidance and the mounting lawsuits threaten restaurants that were essentially following law.

“I’m worried about what happens next,” Dolch said. “There’s 15 lawsuits now. It could be 50 by the end of the year, unless we find a fix.”

**This article was updated to reference Hayber Law Firm’s new name, Hayber, McKenna & Dinsmore**