A proposal to create a public health plan for small employers has some lawmakers and business associations wondering why the state of Connecticut is trying to compete against the state’s flagship industry.

According to the bill, the state of Connecticut – the insurance capital of the world — will allow businesses with 50 or fewer employees the option to buy into Connecticut state employee health insurance coverage.

The proposal isn’t sitting well with Connecticut’s insurance industry, which would find itself competing against the state.

In a press release issued May 13, the Insurance Matters for Connecticut coalition said the program would be an “expensive option for Connecticut’s taxpayer.”

There are 20,000 good paying health plan jobs in the Hartford region that are being recruited by other states. As a state, we need to stay competitive and support the growth of the industry here, which includes pushing back against legislation that says government run insurance is a better model and supporting legislation that will keep a high-skilled workforce in state,” said Steve Jewett, a former health executive and spokesperson for the coalition.

The Connecticut Business and Industry Association also chimed in on the plan. Joseph Brennan, CEO for CBIA said their “primary concern is the impact these proposals will have on the small business health insurance market place.”

“They do not address the underlying cost of healthcare but merely shift costs among different ratepayers,” Brennan said. “In addition, the state simply cannot take on new, costly initiatives when we’re still grappling with huge budget deficits.”

The health insurance plan would be crafted by State Comptroller Kevin Lembo, but according to the bill, final approval of the plan would sidestep the legislature by only requiring approval by the Insurance and Real Estate Committee.

That provision doesn’t sit well with Republicans, who tried unsuccessfully to “box” the bill during the Appropriations Committee meeting on May 1.

“Something that is so disruptive to the individual market and comprehensively changes the industry should get a vote,” said Sen. Kevin Kelly, R-Stratford, who serves as ranking member on the Insurance and Real Estate Committee. “What are they afraid of? If the plan has merit, it will win the day.”

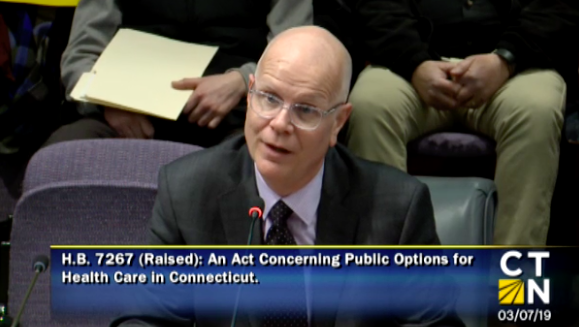

Testifying before the Insurance and Real Estate Committee on March 7, Comptroller Kevin Lembo said “the small employers either can’t afford to provide a plan any longer or just get so frustrated by the changes from year to year that they walk away.”

“The existing market forces are not working to the benefit of the employers and the people who they are trying to provide coverage for,” Lembo said.

Lembo said the state is not burdened with high administrative costs that face insurers in the private market, noting only 2 percent of the cost of the state plan is for administration. “By definition, we have an opportunity to come in with a better-priced product.”

Connecticut currently has a “partnership plan” with municipalities to provide health care coverage for over 18,000 employees and 48,000 members and Lembo testified that offering a similar partnership plan for small businesses will help them avoid escalating health coverage costs.

But the state’s municipal partnership plan ran a $10.3 million deficit in 2018, with costs outpacing premiums.

The Office of Fiscal Analysis was unable to give any hard and fast numbers because the bill simply gives authority to the comptroller to create a plan, but OFA still estimates costs of “at least” $1.5 million in 2020 and $750,000 in 2021.

But taxpayer costs could be higher if the partnerships costs outweigh premiums in the future.

According to the fiscal note, there is no stop-loss coverage if the plan runs into deficit and that could mean future costs for taxpayers. “To the extent claims are in excess of premiums established, there will be a cost to the state,” OFA wrote.

“In a deficit situation, someone has to make up for that,” Kelly said. “It’s either crowd out core services or go to the taxpayer to bailout the inefficiency of state government.”

Lembo said an influx of new individuals into the plan could raise claim payouts initially, but said the state is in the best position “to bear the risk of that.”

Proponents believe that creating a larger pool of premium payers will increase the efficiency of the program, but as the number of participants have grown over the past three years the margins between payouts and premiums have grown tighter, culminating in 2018’s loss.

“In the insurance world premium is rated on risk, not number of people,” Kelly said.

Kelly added that under the legislation, the public option health plan would not be regulated by the Connecticut Insurance Department and therefore not subject to supervision or oversight, other than the Comptroller’s Office.

The other fly in the ointment for the bill could be loss of the state’s exemption from the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act which means the state could potentially open itself up to lawsuits.

That problem was previously broached in 2012 when Gov. Dannel Malloy asked the Employee Benefits Security Administration for an advisory opinion as to whether or not the State of Connecticut would still be exempt from ERISA regulations if it added private employees onto its health plan.

A 2012 advisory opinion concluded Connecticut would no longer be qualified as a “governmental plan” and Connecticut would be forced to comply with ERISA regulations.

“None of our advisory opinions, however, have suggested that the substantial level of private sector participation described in your letter would be permissible in a plan claiming the governmental plan status exemption from ERISA,” wrote Elizabeth Rees, Chief of the Division of Coverage, Reporting and Disclosure for the Office of Regulations and Interpretations.

The Office of Fiscal Analysis also notes the state could lose its ERISA exemption. “Under ERISA, the state would have to comply with fiduciary standards, reporting and disclosure requirements,” OFA wrote in the fiscal note. “Failure to comply with ERISA could subject the state to financial penalties and ‘gives participants the right to sue for benefits and breaches of fiduciary duty.’”

But one of the questions few seem able to answer is why the state would seek to compete with its flagship industry.

Supporters see the measure as a way to help keep health care costs low for small employers and nonprofits, even if it comes at a cost to Connecticut insurance companies.

Jewett wrote the public option bills “threaten to destabilize the entire insurance market” by undercutting private companies by creating a program subsidized with taxpayer dollars, undermining the “$32 million invested annually in the health insurance exchange by offering a competing product” and “overextending Connecticut budget liabilities.”

“If the state can pick on flagship companies, it can certainly pick on mom and pop shops,” Kelly said. “This is uncharted territory. No other state has adopted this.”

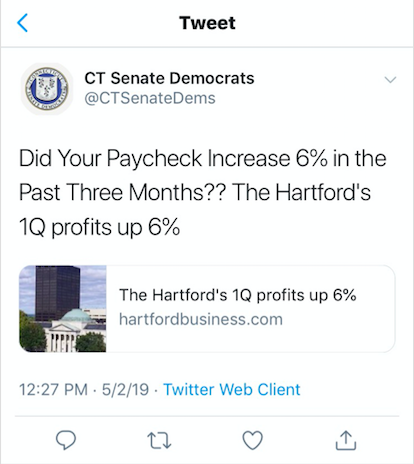

The two bills in the House and Senate are backed heavily by Democratic Party lawmakers and there appears to be little love lost between state Democrats and the state’s major insurers.

On May 2, CT Senate Democrats tweeted out an article showing The Hartford’s first quarter profits up by 6 percent and asking, “Did your paycheck increase 6% in the past three months??” The tweet, however, appears to have since disappeared.

The bills in both the House and Senate are awaiting possible votes.

Gov. Ned Lamont has met with proponents of the bill on May 13, who say that he is wavering on the issue. Religious leaders who advocate for universal health care arrived at Lamont’s office to press the governor to support the legislation.

Lamont issued a statement saying he is “working with my partners in government and health care leaders to develop a ‘Connecticut Option,’ which I believe both responsibly addresses the cost of health care and leverages the considerable expertise of leading employers in our state.”