As some legislative leaders call for tolls on Connecticut’s highways, new revenue estimates from the state show transportation funding is expected to increase by $310 million by 2023.

The Office of Fiscal Analysis and the Office of Policy and Management released their consensus revenue estimates yesterday showing Connecticut may not only take in more tax revenue than anticipated, but that the state’s Special Transportation Fund will also bring in more money to fund infrastructure projects.

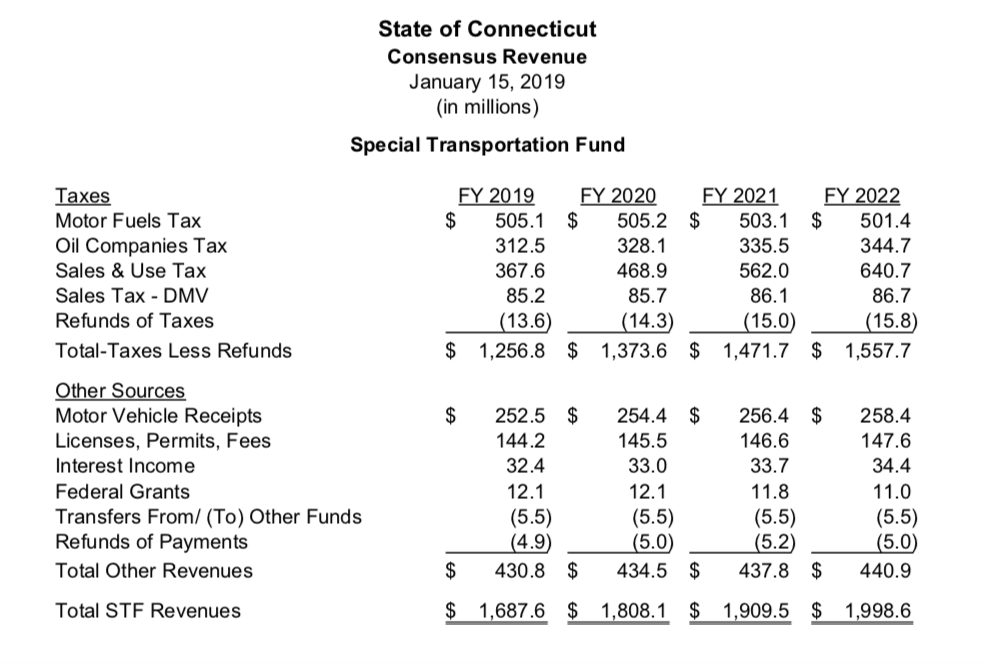

According to OFA, revenue to the STF is expected to increase from $1.68 billion this year to $1.99 billion by 2022.

The growth comes largely from anticipated transfers of sales tax revenue into the STF and from growth in revenue from the oil company gross receipts tax.

Revenue from the state’s gasoline tax is expected to remain slightly lower, taking in $501 million per year.

But the revenue increases are not set in stone, even with the transportation lock box passed by voters in the November 2018 election, which is meant to secure STF funding from “raids” by lawmakers.

That’s because, unlike the gasoline and oil company tax, the sales tax revenue owed to the STF is transferred from the General Fund and not protected by the lock box.

As Connecticut faces budget deficits, lawmakers can withhold part or all of the sales tax meant to fund transportation and repair Connecticut’s roads and bridges.

It wouldn’t be the first time lawmakers held part of the sales tax back from the state’s transportation fund.

In 2016, the STF was scheduled to receive $146.5 million in sales tax transfers but instead only received $109 million.

Again, in 2017, the STF was meant to receive $238.4 million but received only $188 million.

Since 2010, the legislature has “diverted” hundreds of millions in transportation funding that would have been transferred from the General Fund to the STF to help deal with budget deficits.

Those diversions usually occurred when the state received higher than expected revenue from the oil company tax.

The STF may also face increasing expenses from past borrowing and growth in fringe benefit costs for Department of Transportation employees. The growing cost of fringe benefits is related to the state’s unfunded pension liabilities which are driving up labor costs.

Debt service for the STF currently takes up 40 percent of STF funding, but the largest growth in transportation expenditures has been for public transportation and fringe benefit costs.

Connecticut faces projected deficits for the next four years, at least. The revenue projections estimate that deficit may be smaller than anticipated, although much of the increased revenue will be transferred to the state’s Rainy Day Fund because of Connecticut’s new volatility cap.

Gov. Ned Lamont has so far indicated he would only be willing to support tolls on trucks, which would bring in an estimated $200 million per year, but that proposal could face major hurdles as a federal court case challenging Rhode Island’s truck-only tolls remains undecided.

Former Gov. Dannel Malloy called for both an increase to the gasoline tax and tolls for all drivers on Connecticut’s highways. His recommendations were echoed by Lamont’s Transportation Advisory Committee when the group released its recommendations in December.

Democratic Party leaders who now control both the House and Senate have indicated they support tolling both cars and trucks, which would bring in an estimated $1.086 billion per year to the state.

Republican leaders in the House and Senate have said the state does not need tolls to meet its transportation needs and last year’s bipartisan budget agreement “allowed us to contribute a historic amount of funding to transportation.”