Connecticut lawmakers and Gov. Ned Lamont bridged a $3.5 billion biannual budget deficit during the 2021 legislative session, largely using federal COVID relief funds combined with some revenue and accounting adjustments the state has employed for years, such as diverting sales tax revenue away from the Municipal Revenue Sharing Account and continuing the corporate tax surcharge.

That, combined with better-than-expected income tax revenue coming from Wall Street earnings, left Connecticut able to pay all its bills for fiscal years 2022 and 2023, while maintaining a full rainy day fund and even paying down some of its pension debt.

But what happens after the federal COVID money dries up after 2023?

According to the Office of Fiscal Analysis, Connecticut’s 2024-2025 budget cycle will again see deficits, this time totaling roughly $2 billion. That estimate does not include any programs the state establishes using ARPA funds that may continue after the federal money is gone.

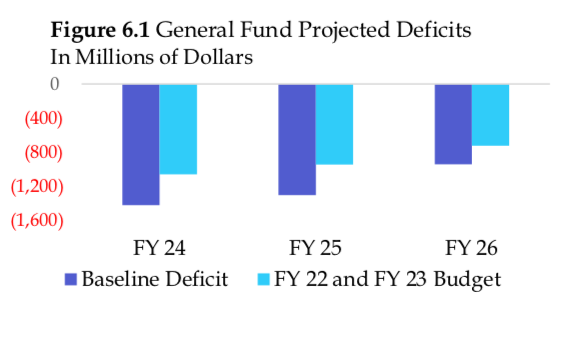

“The General Fund is projected to be in deficit by between $725 million and $1.1 billion per fiscal year during FY 24 to FY 26,” the OFA budget report says. “Nonetheless, policies enacted in the budget improve projected out year deficits, as compared to the baseline estimates, by a range of $217 million to $361 million per fiscal year.”

However, Connecticut has over $3 billion in its reserve funds, built up over the past few years through Connecticut’s volatility cap, which transfers a percentage of income taxes derived from volatile investment earnings into the state’s rainy day fund if that revenue exceeds official projections.

The budget reserve fund could be used to cover some or all of the state’s deficit in those years, if lawmakers or the governor are willing to use them, but the OFA projects that 2026 will also see a $725 million deficit in 2026 alone, so there will likely be hesitation to use up too much of Connecticut’s reserve funds.

More likely will be a combination of reserve funds, revenue increases through either the continuation of tax policies set to expire – once again the corporate tax surcharge – or possible tax increases as calls by some lawmakers to increase taxes on the wealthy or on investment income have gained steam during the pandemic.

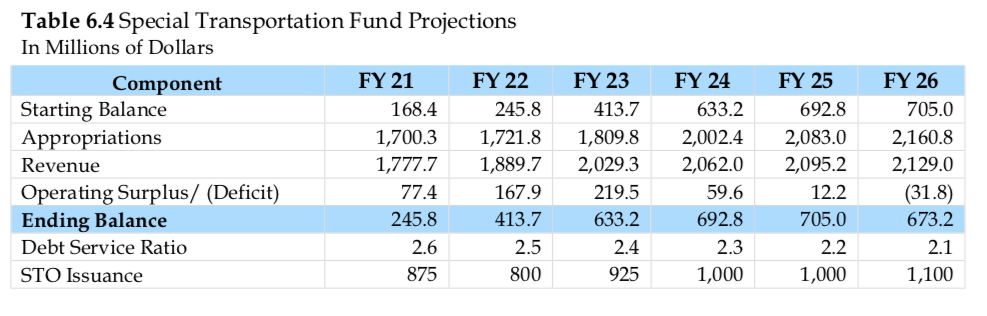

Budget projections also show that Connecticut’s Special Transportation Fund will actually take in more money than it pays out and not face a deficit until 2026, when it will see a $31.8 million shortfall. However, STF will have $705 million in its accumulated balance to cover the loss.

According to the OFA report, “The cumulative balance is expected to grow significantly through the biennium due to the sales tax transfer growing to 100% in FY23 and anticipated temporary federal support for transportation projects.”

Lamont was able to pass a highway use tax on trucks based on their weight and the miles they drive in the state, which is expected to bring in roughly $90 million by 2024 when the program is fully in place.

And while it never came to a vote during the 2021 session, Lamont and some Democratic lawmakers continue to push for the Transportation and Climate Initiative, arguing that it will provide an additional revenue stream to support public transportation and electric vehicle usage.

Naturally, all these projections are based on present economic, fiscal and political conditions which can change rapidly – no one could have predicted the 2020 pandemic and few believed that Wall Street would experience such a quick turnaround or that the federal government would infuse billions into state coffers.

The out-year projections show that Connecticut will likely continue its ongoing cycle of budget deficits, except this time with a full savings account, but that doesn’t mean the state is out of the woods or taxpayers are off the hook for possible future increases.

Connecticut will likely have to contend with a slow economic recovery from the pandemic. The state had already experienced a decade of slow job and wage growth before 2020 and economists believe it will take another year or two before Connecticut recovers the jobs lost during the pandemic.