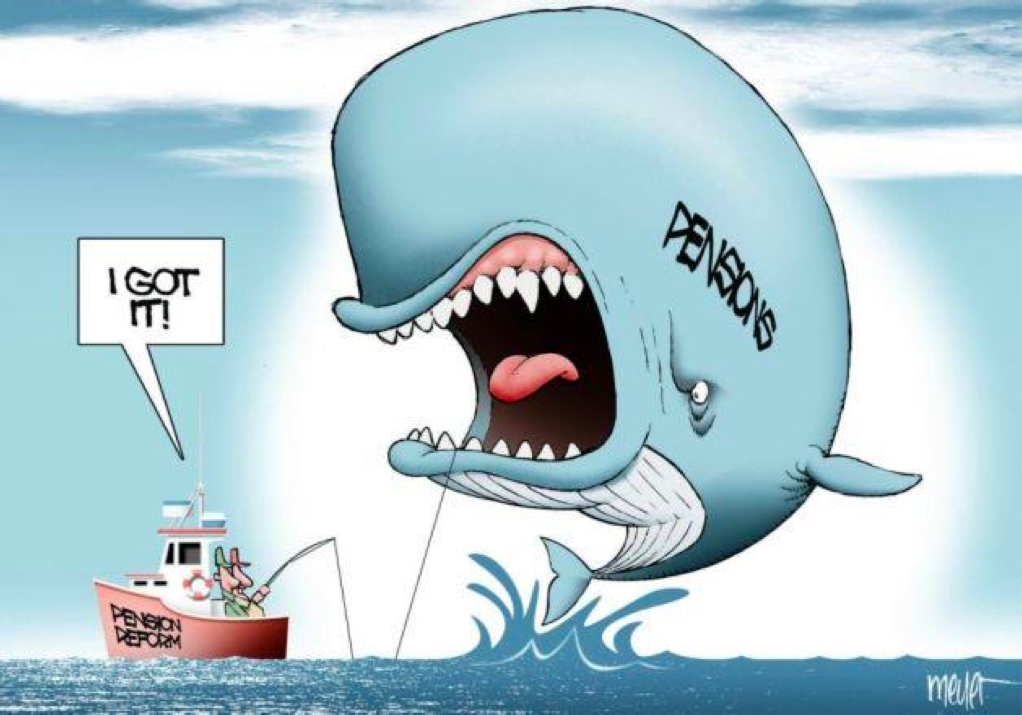

Connecticut’s long-term debt grew $8.4 billion between 2019 and 2020 due to increased liabilities for Connecticut’s retirement systems, according to the newly released Comprehensive Annual Financial Report.

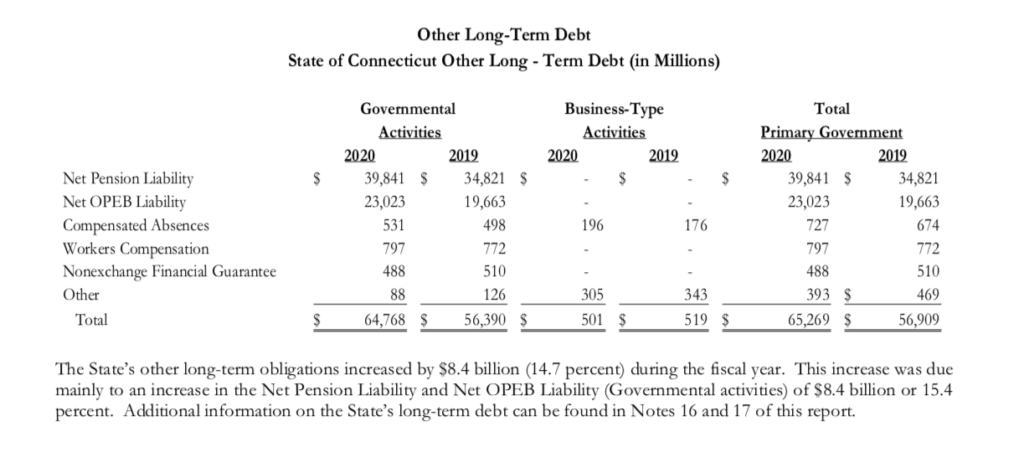

Connecticut’s unfunded pension and OPEB liabilities increased from $56.3 billion in 2019 to $64.7 billion in 2020.

The 15.4 percent increase “was due mainly to an increase in the Net Position Liability and Net OPEB Liability of $8.4 billion,” the report says.

Unfunded pension liabilities grew by $5 billion and OPEB liabilities grew by roughly $3.4 billion. Those rising debts could increase the state’s future annual payments, which will total $3.8 billion this year.

According to the Comptroller’s Office, the increase in unfunded liabilities is due to a number of factors, including changing discount rates, increasing medical costs and an increase in net liabilities.

As part of his 2019 teacher pension fix, Gov. Ned Lamont reamortized the teacher pension debt and lowered the assumed rate of return for TRS investments from 8 percent to 6.9 percent. The lower discount rate, however, increased the unfunded liabilities for TRS by $3.9 billion.

The state employee pension system saw an unfunded liability increase of $1.1 billion due to “net actuarial experience loss” during the 2018 fiscal year, according to the Comptroller’s Office.

The $3.4 billion increase in unfunded liabilities for Connecticut’s OPEB fund includes $2.4 billion from increasing healthcare costs and $1 billion from a lower assumed rate of return.

Assumed rates of return — also referred to as discount rates — can wildly affect total pension liabilities as the state bases its annual payment on expected returns from pension fund investments. The higher the rate of return, the smaller the annual payment made by the state and vice versa.

However, overly optimistic rates of return can lead to the state underfunding the pension plan even when it is making the full annual payments as Connecticut has since 2014.

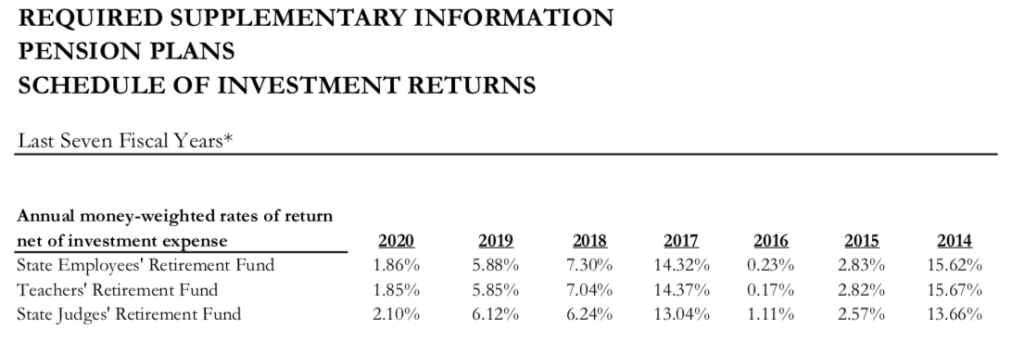

Teacher pension investments have not reached their assumed rate of return for three straight years, including 2020 when the fund returned less than 2 percent, according to the CAFR.

The assumed rate of return for state employee pensions was lowered to 6.9 percent by Gov. Dannel Malloy when he reamortized the state employee pension debt in 2017.

Over seven years Connecticut’s pension funds have seen either feast or famine, according to figures presented in the 2020 CAFR. SERS had an average rate of return of 6.86 percent, while TRS averaged 6.82 percent.

However, Connecticut’s unfunded retirement liabilities were growing before Malloy and Lamont lowered the discount rates, and the larger the unfunded liability, the more taxpayers are on the hook for making full annual payments.

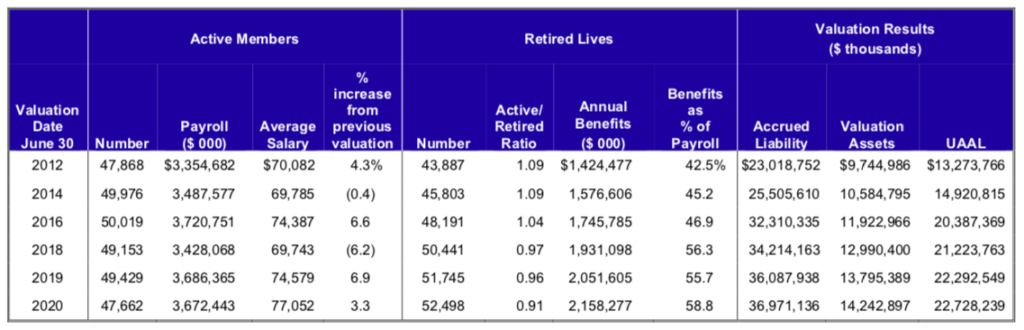

According to the 2020 SERS Valuation, Connecticut’s unfunded state employee pension liabilities have grown from $13.2 billion in 2012 to $22.7 billion in 2020, an increase of nearly 72 percent.

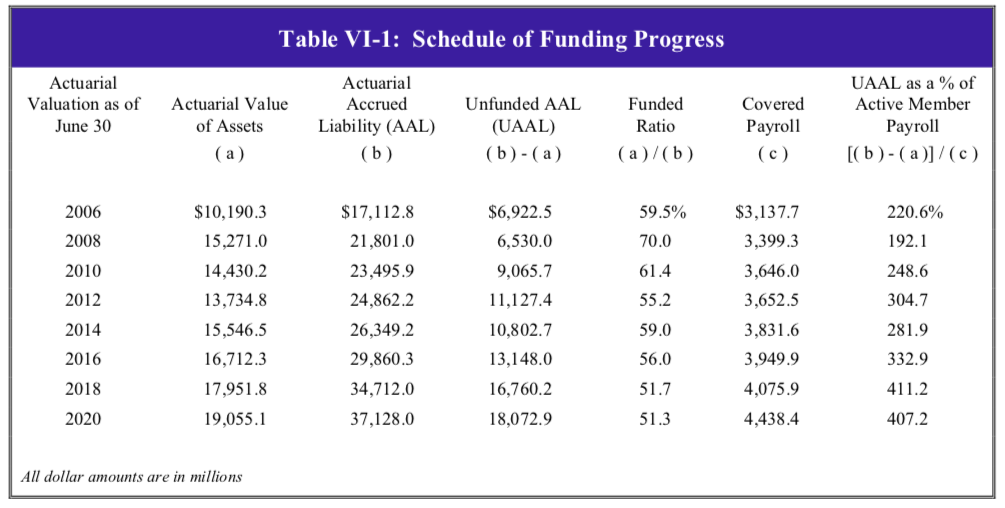

Likewise, Connecticut unfunded teacher pension liabilities increased 62.5 percent, growing from $11.1 billion in 2012 to $18 billion in 2020, despite the state making its full annual payments as required by a 2008 bond covenant.

Meanwhile the funding ratio for SERS dropped from 42 percent funded to 38 percent and funding for TRS dropped from 59 percent to 51.3 percent over the same time period.

The effects of Connecticut’s state pension debt trickles down into all levels of government, driving up tuition at Connecticut’s state colleges and universities, limiting research grant funding at UConn Health Center, jeopardizing growth at Bradley International Airport and draining the state’s beleaguered Special Transportation Fund.

According to the CAFR, “STF contributions for SERS retirement increased $20.8 million in FY 2020, again primarily due to higher costs for unfunded pension liability.” Comparatively, debt service costs for the STF increased only $9 million.

Connecticut’s overall long-term debt, including bonded debt, totaled $92.1 billion, according to the Comptroller’s annual report. Bonded debt accounted for $27.4 billion, meaning Connecticut’s unfunded retirement obligations amount to 70 percent of Connecticut’s total long-term debt.

Connecticut’s bonded debt and retirement liabilities are, along with Medicaid, part of the state’s fixed costs which now consume 52 percent of the state’s total budget, according to the Office of Fiscal Analysis.

Both Gov. Malloy and Gov. Lamont reamortized the state employee and teacher pension debt, stretching out payments until 2045 to prevent unsupportable spikes in the annual payments, which, under certain scenarios, could have reached $6 billion per year.

Reamortizing the debt lowered the projected annual payments but added to the overall payoff amount by adding years of liability payments onto future generations.

LISA JOLLEY

March 4, 2021 @ 11:20 am

Marc, aRE YOU FAMILIAR WITH aRTICLE v OF THE u.s. cONSTITUTION, WHICH ALLOWS CITIZENS TO HOLD A CONVENTION OF STATES TO PROPOSE AMENDMENTS TO THE CONSTITUTION, WITHOUT INVOLVING CONGRESS OR THE PRESIDENT? pLEASE GO TO http://WWW.CONVENTIONOFSTATES.COM AND READ ABOUT OUR GOALS. PLEASE SIGN THE PETITION AND SHARE OUR WEBSITE. THANK YOU.

Lyn

March 7, 2021 @ 4:36 pm

What is the impact to ct. Pensions with the blue state bailout- Eppra in the american rescue plan?