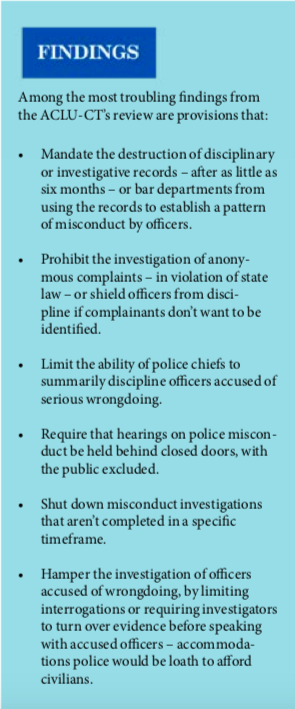

The American Civil Liberties Union of Connecticut issued a report saying municipal and state police union contracts in Connecticut violate state statute, limit disciplinary action against officers, prevent complete records from being released to the public and limit misconduct investigations.

The study comes as the Connecticut legislature considers a special session in July to address, among other things, police accountability following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis and nationwide protests.

“A review by the ACLU of Connecticut of every police union contract in Connecticut reveals that many include language that shields police misconduct and weakens accountability and oversight,” the CT ACLU wrote in their report. “In some communities the collective bargaining agreement conflicts with state law.”

Among those conflicts with state law is disciplinary and complaint records for officers. Some police union contracts call for the destruction or removal disciplinary records after short periods of time, according to the report.

Connecticut’s Record Retention Schedule for municipalities requires disciplinary records, including those that result in no suspension, dismissal or litigation, to be maintained for five years, and discipline that did result in action be maintained for the entirety of employment plus 30 years.

According to the footnotes in Connecticut’s Records Retention Schedule, “The destruction of public records, including public employee discipline records, is an illegal subject of collective bargaining agreements.”

The footnote references a thirty-year old Connecticut Supreme Court case, in which AFSMCE required that an East Haven police officer’s records be destroyed in exchange for him resigning from the department.

According to the Supreme Court ruling, “The destruction of public records, therefore, is an illegal subject of collective bargaining, and any collective bargaining agreement, arbitration award or grievance settlement requiring such destruction is null and void.”

The report also found that in 19 different police union contracts, anonymous civilian complaints are not investigated or disregarded, which the CT ACLU says violates mandatory policy.

“The timeliness of a complaint can be considered when evaluating the evidence and deciding on discipline, but older complaints cannot by law be summarily dismissed, just as anonymous complaints cannot,” the ACLU wrote.

The conflicts between municipal police union contracts and state law, however, should not exist.

Although state employee contracts can supersede state law, municipal union contracts cannot, meaning that some of the problems outlined in the ACLU’s report could be remedied by simply enforcing existing state law.

According to a 2019 report by the Office of Legislative Research, municipal collective bargaining contracts can only supersede conflicting municipal charters, special acts, rules and regulations or ordinances.

The ability of municipal contracts to supersede state law is limited to regulating work hours for police and firefighters or covering employees under the state’s Municipal Retirement System.

The Connecticut State Police contract, the study noted, expanded the Freedom of Information exemption for state police. Under the contract, personnel records cannot be released without the authorization of the officer and internal affairs investigations that exonerated an officer are kept secret.

According to the Connecticut Freedom of Information Commission, the Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection have been interpreting this provision in the contract “very broadly,” resulting in complaints that the department is violating FOI statutes.

The report also found that contracts limit access to police disciplinary hearings and “set short time limits to complete an investigation.”

“Getting to the bottom of police misconduct can take some time,” the report says. “But some contracts set arbitrary expiration dates, forcing departments to abandon investigations if they aren’t completed quickly enough.”

Despite the conflicts with state law, ACLU’s study found that little changes when police union contracts are renegotiated other than salaries and benefits.

The report found police unions have spent over $1.1 million on lobbying, “often using those well-financed efforts to oppose police accountability measures and to argue for funding with no strings attached.”

“In addition, the Connecticut Police Chiefs Association, an affinity group that lobbies at the state level and represents police management, has almost always argued in lockstep with those unions,” the ACLU wrote.

Examining the influence of police union contracts on policing practices and discipline was part of the recommendations released by the Police Accountability and Transparency Task Force.

The CT ACLU also listed a series of policy changes related to police union contracts in their report, including requiring that municipalities remove contract provisions that conflict with state law, remove limitations on police chiefs and commissions’ ability to discipline officers, remove provisions that block access to records.

“Legislators must also take more seriously their responsibility to review state contract provisions that conflict with state law,” the CT ACLU wrote. “Such provisions – like those in the State Police contract – attain the force of law when contracts are approved by the legislature. And lawmakers repeatedly have been reluctant to step in and reject contract provisions that harm the public.”

James Hagan

July 7, 2020 @ 6:00 pm

Is anyone really surprised that State (Union) contracts run afoul of law, GAP’s (generally accepted practices), FOI guidelines, and/ or any level of transparency?

And does anyone think that a single democratic legislator will oppose a future contract or vote to correct a current contract, when the unions “pay to play” our (mostly democratic) legislators?

I didn’t think so.

Thad Stewart

July 11, 2020 @ 1:59 pm

If the private sector was run like this, they would be out of business, YESTERDAY! The fact that the politicians have sold out to the unions should be punishable by law.