Connecticut’s teacher pension debt is officially listed at $16.8 billion, but a new study says that figure might be much higher.

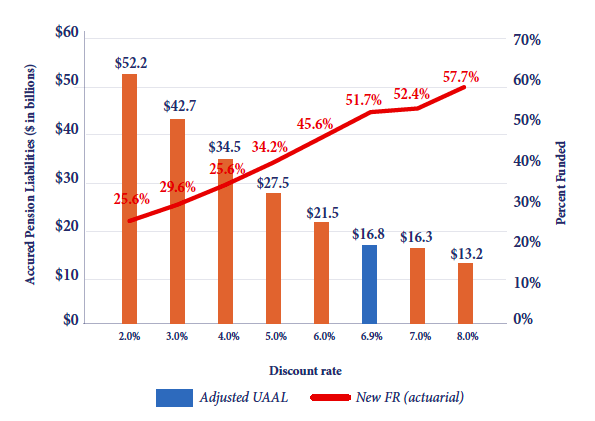

According to a new study published by Yankee Institute, Connecticut’s discount rate for its teacher pension system is under-stating its unfunded liabilities by using too high of a discount rate.

“Because public employees in Connecticut have very strong protections in place for their pension benefits, the value of benefits are significantly higher than stated,” wrote study author and Director of Policy and Analysis for EdChoice Martin F. Lueken, Ph.D. “Unfunded liabilities may be more than three times what is stated, up to $50 billion.”

The difference comes from Connecticut’s assumed rate of return on its pension market investments and the state’s discount rate.

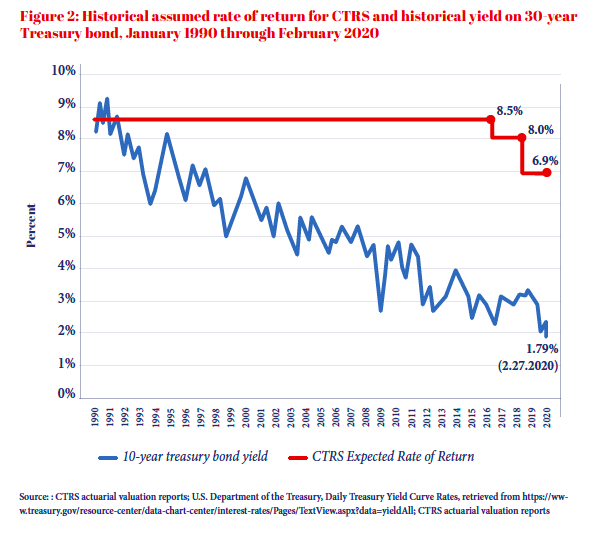

Connecticut assumes a 6.9 percent rate of return on its pension investments and uses that assumption to determine annual payments into the pension system. The higher the assumed rate of return, the more a government can “discount” it’s annual payments into its pension system.

But Lueken argues that regardless of what the assumed rate of return is, the discount rate should be much lower, reflecting a risk-free rate closer to the yield of Treasury bond, which is currently less than 2 percent.

Gov. Dannel Malloy and the Teachers Retirement Board in 2016 lowered the assumed rate of return and discount rate from 8.5 percent to 8 percent, and Gov. Ned Lamont lowered the rate again in 2019 to 6.9 percent.

The 8 percent discount rate made sense in the early 1990s, when it matched a 10-year treasury bond yield. However, since that time the treasury bond yield has fallen, while Connecticut’s assumptions remained largely the same.

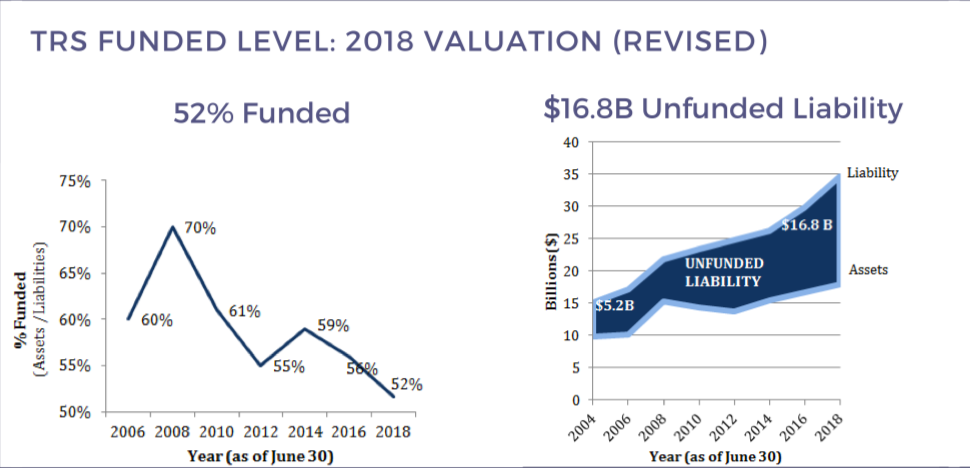

According to reports from the Connecticut Office of Fiscal Analysis, Connecticut’s unfunded pension liability for teachers has grown significantly since 2004, despite the state making full annual payments toward to the Teachers Retirement System under a 2008 bond covenant.

Since 2008, teacher pension funding has declined from 70 percent to 52 percent in 2018 and payments have risen from roughly $500 million to $1.2 billion.

Part of that may have to do with the timing of a $2 billion bond the state took out in 2008 to help boost the Teachers Retirement System. The bond came on the eve of a recession, which resulted in negative market returns for the pension fund.

Although Gov. Lamont lowered the discount rate and assumed rate of return in 2019, and State Treasurer Shawn Wooden enacted risk mitigation for Connecticut’s investments, the market’s downturn in response to the COVID-19 pandemic could see a repeat of 2008.

Lamont restructured the teacher pension fund, stretching out payments until nearly 2050 to avoid annual payments spiking to unsupportable levels, which the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College estimated could grow as high as $6 billion per year depending on market returns.

Lueken recommends separating return assumptions from the discount rate and basing state contributions to the pension fund on a lower, risk-free rate.

But this might not be possible as Connecticut faces a Catch-22 with its pension funding.

Specifically, lowering the discount rate increases the state’s annual contribution and with Connecticut now facing multi-billion deficits over the next few years due to the COVID-19 recession, the state will already be struggling to make its annual payments.

The re-amortization of the unfunded teacher pension liabilities added more debt onto the total payoff cost, much like refinancing a mortgage, and that means it shifted costs onto future taxpayers in Connecticut.

“When pension plans incorrectly measure the value of benefits, they place future taxpayers at risk of having to pay for legacy costs because funds are not completely pre-funded,” Lueken wrote. “Connecticut taxpayers concerned with intergenerational equity should consider options to pay down debt today.”

Michael Joseph Lamirande

July 4, 2020 @ 10:52 am

God Bless you all at the Yankee Institute for speaking the truth about our financial Armageddon. Our only salvation seems to be filing bankruptcy to re-configure the pension and liability arrangements. As bad as Connecticuts’ situation has become, a handful of states have far exceeded our irresponsibility including California, New York, and Illinois. This is incredibly bad news for our nation and the world since the world looks to the United States for leadership and guidance. For all the faithful out there, keep up the prayers to save our country and the world from the financial disaster that looms just ahead.