It’s not yet clear how Governor-Elect Lamont intends to govern. What is already clear is that while he comes into office with sizeable supporting majorities in each house of the legislature, those majorities come at a cost.

The Progressive Caucus in the House includes about half of the Democratic majority, while the far-left influence in the Senate may be even greater. These progressives can be expected to demand their pound of flesh. Already, de facto House progressive spokesman Josh Elliot, D-Hamden, has indicated which cuts of meat they expect to take: a minimum-wage hike; pot and sports-betting legalization (and taxation); paid family & medical leave; and establishment of tolls.

Given the general progressive bent toward increased state involvement in citizens’ lives and increased government spending, the new governor’s first duty – returning Connecticut to fiscal stability and economic growth – will likely have been complicated by these progressive gains in the legislature. The problem has already become apparent in one important regard: a disagreement about the appropriate use of the state’s Rainy Day Fund.

Legislative leaders have indicated a desire to dip into the Rainy Day Fund in 2019 as a way to avoid grappling fully with the state’s massive structural deficit.

To his significant credit, Governor-Elect Lamont has disagreed. He has flatly declared his unwillingness to tap the state’s Rainy Day Fund in 2019. He has also, post-election, restated that he is not willing to raise tax rates on Connecticut’s already hard-pressed residents.

Given that Massachusetts’ income tax rate is scheduled to fall in each of the next two years, to less than three-quarters of Connecticut’s rate, and given that Connecticut is already losing top taxpaying businesses and residents to friendlier jurisdictions, this latter promise is vital. But so is the need to keep the Rainy Day fund intact until the next recession.

This fund, formally known as the Budget Reserve Fund, was reformed in 2016 with bipartisan support to make it a national model. The reforms earned the ringing endorsement of the non-partisan Pew Charitable Trusts as legislation “consistent with the best practices identified by Pew to smooth revenue volatility and build savings during times of growth.”

So far, it has fulfilled that mission. A rare bright spot on Connecticut’s otherwise dismal economic landscape, the fund now nears $2 billion in assets. These assets are supposed to help Connecticut to weather the next recession. They should be reserved for that purpose alone.

Unfortunately, the reformed fund includes a provision that allows the assets to be used outside of a recession with the vote of a two-thirds majority of each house. Speaker of the House Joe Aresimowicz has challenged Lamont, saying that the override option be maintained for the 2019 budget.

This is a terrible idea.

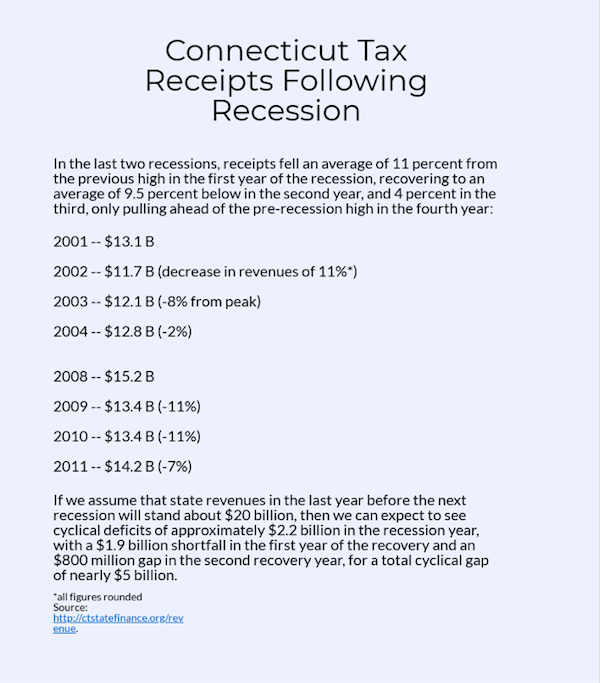

There is always another recession coming. Business-cycle history suggest the next one is only a year or two off, as Lamont himself has recognized. When the next recession comes, we should expect it to cut state revenues by more than $2 billion in the first year, with full recovery coming only in the fourth year. This means that the next recession could well blow an aggregate $5 billion cyclical hole in the state budget, by a conservative estimate.

If there is a recession, we could face a shortfall of about $12.5 billion over three years, or more than 20 percent of the pre-recession baseline. In fact, we know it would be significantly bigger than that, because recessions have secondary and tertiary effects on state spending, pushing up costs for benefits and other social services.

If every dollar now in the fund, and everything put aside until that recession, is saved, we might be able to cover as much as half of that cyclical gap. Making up the remaining $2.5 billion or so over three years would be hard and unpleasant. With the realistic expectation that the deficit will disappear in the fourth year, however, the task would probably be manageable.

Compare that scenario to one in which the state uses the Rainy Day fund in 2019 to paper over the structural deficit that still exists even in these relative boom times.

Right now, the Rainy Day Fund would just about cover that structural deficit for one year. But now assume that the recession year comes in 2020, and results in budget shortfalls at the average of the last two recessions. There would be no Rainy Day Fund left to cushion the blow, and the structural deficit would remain and even grow in each of those years.

If we assume that the structural deficit for 2020 will be, as now projected, about $2.3 billion, and that it will grow slowly but steadily thereafter, we can assume an average structural deficit over the three years at about $2.5 billion (on average) annually, for a total of about $7.5 billion.

If there is a recession, we could face a shortfall of about $12.5 billion over three years, or more than 20 percent of the pre-recession baseline. In fact, we know it would be significantly bigger than that, because recessions have secondary and tertiary effects on state spending, pushing up costs for benefits and other social services.

Worst of all, we’d enter that whirlwind without having made any provision to address the ever-growing structural deficit. So there would be no light at all at the end of the tunnel, just ever-increasing deficits stretching out to the horizon.

Given Connecticut’s economic problems, high current debt level, and already fleeing tax base, that could well be the death knell for the state.

Stand fast, Governor-Elect Lamont. For the sake of Connecticut, don’t touch the Rainy Day Fund in 2019. Use this reprieve to fix the structural deficit, without a net tax increase.