One of the state’s residential facilities for the intellectually impaired was staffed using mandatory overtime 93 percent of the time even though Medicaid would fund half the cost of hiring more staff, according to a report by the Connecticut State Auditors.

A review of staffing over the course of 730 days at the Lower Fairfield Regional Center found mandatory overtime was used 675 days, contributing to both higher operating costs and long-term pension costs for the state.

The Department of Developmental Services, which runs the facility, said they had delayed hiring more staff because the DDS was scheduled to move 30 group homes over to private operation, which would free up more staff for the full-time residential facility.

“However, the conversions were placed on hold during negotiations with the bargaining units,” DDS said in their response, and has since received approval to hire 130 part-time staff.

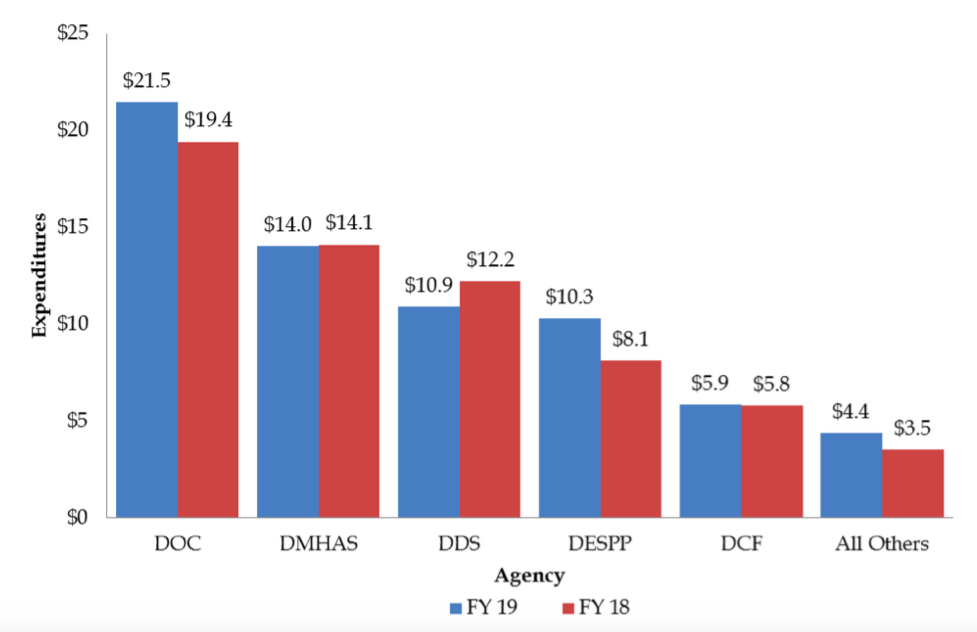

DDS accounts for a significant amount of overtime spending, according to overtime reports from the Office of Fiscal Analysis, but DDS Spokeswoman Kathryn Rock-Burns says the department has made strides in reducing overtime, including moving group home facilities to private care.

“Since the close of FY 2016, DDS has completed conversion of 12 public Community Living Arrangements (CLAs, also referred to as group homes) to private operation,” Rock-Burns said in an email.

“During the course of FY 2019, we expect to complete an additional five conversions and two closures of public CLAs. The staff from each of these 19 CLAs have been or will be redeployed to vacant shifts in other publicly operated programs across the agency, including Lower Fairfield Regional Center,” Rock-Burns wrote.

Rock-Burns also says DDS has filled “more than 100 direct care staff vacancies” and notes first quarter agency overtime spending has been reduced by 10.9 percent.

Private, non-profit healthcare providers have long argued the state could save a significant amount of money in both operating costs and legacy costs by transferring state facilities over to private care.

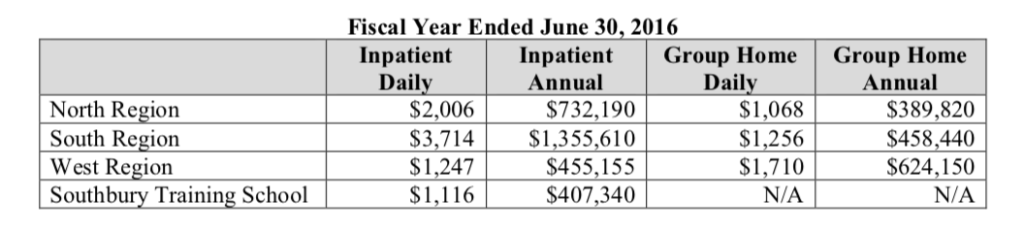

According to the state audit, in 2016 an individual living in a state-run group home cost between $389,820 and $624,150 per year. For in-patient care, the cost increases up to $1.3 million per year.

However, according to The Connecticut Community Nonprofit Alliance, nonprofit providers can provide those same services for much lower cost.

According to a Candidate Bulletin by The Alliance, the state could save $152,000 per individual per year for care of those with intellectual disabilities and $7,000 per year for those who require mental health services.

A 2011 report by the General Assembly’s Program Review and Investigations Committee, placed the average cost for state inpatient care at Connecticut’s regional centers at $325,835 and for group homes at $313,533.

Those figures have increased dramatically over the past eight years.

According to the audit, the average cost per person requiring in-patient care at one of Connecticut’s three regional centers and Southbury Training School was $737,573.

For care in a group home, the average was $490,803.

In the past, President of CT Alliance Gian-Carl Casa has said the state could save a total of $300 million by shifting state services to private providers.

“While the SEBAC agreement adopted in 2017 prevents layoffs until 2022, the agreement allows conversion of services to the nonprofit sector to continue through attrition and the assignment of state employees to other duties,” The Alliance’s Candidate Bulletin says. “Nonprofits don’t have the long-term debt obligations associated with healthcare and retirement payments and can more easily manage overtime.”

Connecticut currently provides services to the most-needy using both state-run services through agencies like DDS and private, non-profit providers who are forced to compete with state agencies for both funding and staff.

According to the audit, 2,089 people were on a waiting list for services as of 2016. The overall number of people waiting for services declined as the state shifted more services to private providers and offered more in-home services.

The Lower Fairfield Regional Center is an in-patient facility, but the transfer of group homes to private operation frees up state employees to help cover staffing shortages at the more-expensive in-patient facility.

According to the DDS website, the state currently only operates three regional centers, serving “approximately 150 individuals.”