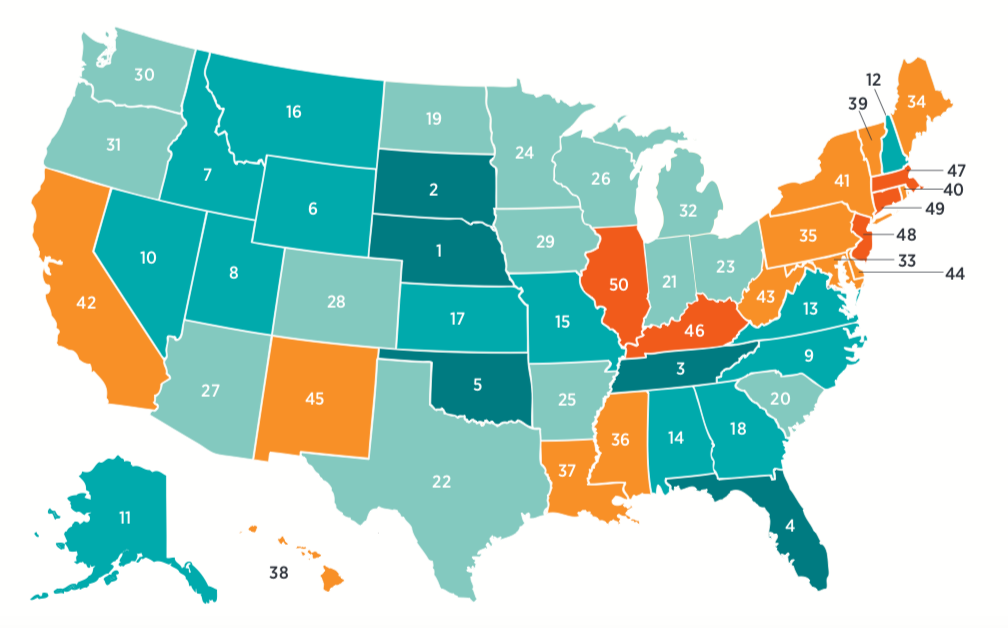

Connecticut dropped twelve places to rank second worst in the nation for fiscal solvency, according to an annual ranking of states released last week by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

The same study last year ranked Connecticut at 37, but this year the Nutmeg State dropped to 49, only beating out Illinois.

More interesting – and perhaps alarming – is that the Mercatus study is based on Connecticut’s 2016 financial report, the year following Gov. Dannel Malloy’s 2015 tax increase, which introduced a new top marginal income tax rate, limited corporate deductions and increased taxes on hospitals.

According to Mercatus, the state only took in enough revenue that year to cover 92 percent of expenses, and the state had to turn to its Rainy Day Fund in order to shore up a budget deficit.

According to State Comptroller Kevin Lembo in the 2016 financial report, revenue from the 2015 tax increase “was well below the original anticipated rate of growth,” and 80 percent of the increase in state spending was attributable to the growth of paying for Connecticut’s bonded debt and the State Employee Retirement System.

Those expenses – part of Connecticut’s fixed costs – are projected to continue growing for the foreseeable future, although a refinancing of SERS debt in 2017 and the implementation of a bonding cap have helped mitigate some of the growth.

Despite the relatively high ranking in last year’s study by Mercatus, Connecticut’s 2015 financial statement wasn’t exactly a rosy picture: the state was in deficit that year, too.

Olivia Gonzalez, one of the authors of the annual report, says Connecticut fared better last year because, despite the budget deficit, the state was moving in the right direction toward fiscal solvency.

According to last year’s study, Connecticut saw a revenue increase of 4.7 percent. Expenses also declined 11 percent, giving the state a positive net position even though it still faced a yearly deficit.

“Connecticut is a unique example of a state that has high long-term liabilities, but in one year (2015) happened to have a sufficient enough increase in revenues to move its financials in a positive direction, but not quite enough to remove its financial problems altogether,” Gonzalez said in an email.

But the increased revenues related to the 2015 tax increase were not enough to keep Connecticut from taking a big step backwards.

There was also a change in Mercatus’ methodology for ranking states’ fiscal solvency.

Under the new methodology, however, Connecticut would have dropped from 40th in 2017 to 49th this year.

Connecticut’s 2018 score was the worst in the past ten years, according to the report, although the state has never scored above a 40 based on Mercatus’ adjusted methodology.

Connecticut’s fiscal future doesn’t look particularly bright, either.

Connecticut faced down a major biennial budget deficit in 2017, forcing the legislature into special session well into the autumn months in order to pass a workable budget.

Malloy also negotiated with the state employee unions to achieve $1.5 billion in savings through higher pension contributions for union members and increased contributions toward medical premiums and costs.

But Connecticut’s fiscal problems remain daunting. The Office of Fiscal Analysis projects a deficit of $4.5 billion for the 2021-2022 biennium and a $6.6 billion deficit for 2023-2024.

While the concessions deal with SEBAC saved some money in the short term, it also granted a no layoff provision until 2022, a one-time lump sum bonus to employees, two rounds of state employee pay increases, and extended the over-arching SEBAC contract until 2027.

The pay increases will increase state labor expenses by $353 million in 2021 and the no-layoff provision prevents any meaningful reduction in the size of Connecticut’s workforce until 2022.

The extension of the SEBAC contract prevents lawmakers from reforming the pension system in order to avert more potential problems in the future without the approval of public sector union officials – an unlikely prospect, considering the latest concessions agreement.

Increasing costs for Connecticut’s unfunded pension and OPEB liabilities and bonded debt will weigh heavily on the state budget for at least the next five years.

The Mercatus study offered two different views of Connecticut’s pension and OPEB debt: one using the state’s numbers and another using a “risk free” discount rate.

On the books, Connecticut faces an unfunded pension and OPEB liability of $57.2 billion, as of 2016.

However, based on the risk-free calculation – meant to safeguard the state from wild swings in the stock market which can negatively affect pension returns – that figure becomes $143.5 billion.

Mercatus notes that Connecticut’s long-term liabilities have grown from “87 percent of assets to more than 200 percent of assets, and the state’s unfunded pensions relative to state income also more than doubled from 19 percent to 48 percent” between 2006 and 2016.

Union leaders have argued the state must raise taxes on top earners again and increase taxes on businesses to solve the state’s future deficits.