Data collected from the Connecticut Office of Policy and Management appears to show Connecticut’s property taxes are being balanced on the backs of residents with low-value homes.

A report by the Western Connecticut Council of Governments, which analyzed property taxes, appraisals, and home sales for 169 Connecticut municipalities between 2011 and 2014, showed low-value homes are often appraised for more than they’re worth, leading to higher property taxes for those who can least afford it.

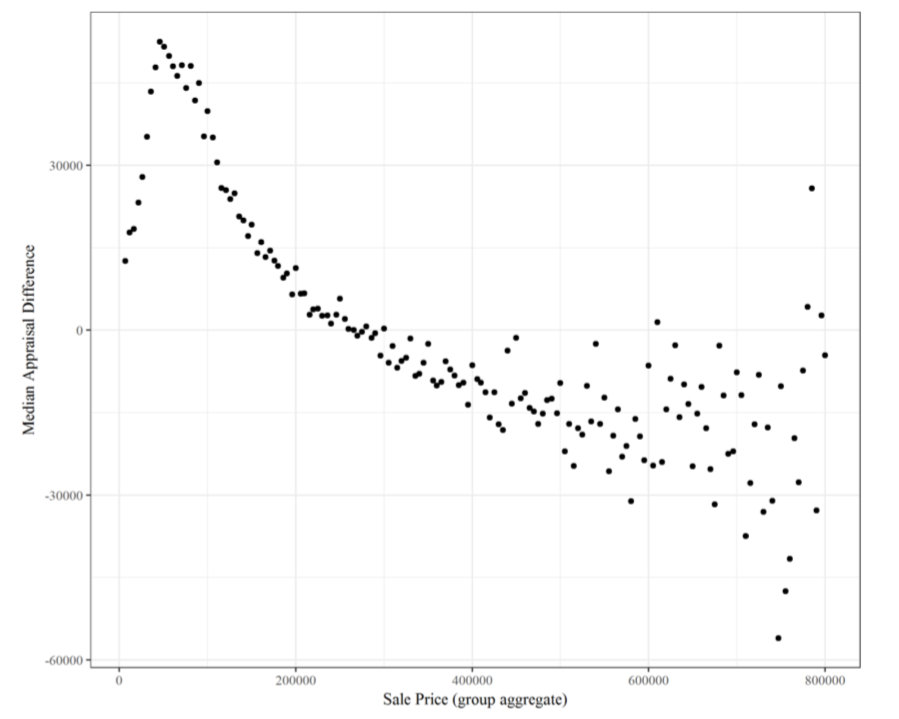

The data showed that Connecticut, as a whole, over-appraised low-value residential properties by 32 percent, while staying within 3 percent of true market value for medium to high-value homes.

A “low-value home” is defined as any residential property in the bottom 25 percent of sale prices statewide.

For an average Connecticut mill rate of 30.78, the owner of a home with a market value of $150,000 could be paying over $900 per year more in property taxes due to the high appraisal.

For towns and cities with high mill rates, that figure grows substantially. In Waterbury, which had a very high appraisal bias, that same homeowner could pay over $2,500 per year more in property taxes due to the city’s 58.22 mill rate.

In general, appraisal bias was highest for municipalities which face budgetary problems combined with lower median home values and residents with lower median incomes.

In particular, appraisals of medium- and high-value properties are typically within 3% of true market value, while appraisers overestimate the value of low-value properties, often by upwards of 30%. This represents a sub- stantial additional tax burden for owners of low-value properties. In addition, we find that wealthier towns tend to have more accurate and less biased appraisals.

According to the report, the difference in valuations may be related to the 2008 recession and housing market collapse. Connecticut has yet to fully recover from the recession in terms of jobs or home values; Connecticut’s home value growth was the slowest in the nation between 2012 and 2017, according to figures from the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

“Nonetheless, the results of this analysis raise serious concerns,” the report says. “Substantial differences between how low and high- value properties are treated results in a significant tax burden shift from wealthier to less wealthy property owners and indicates potential bias in the appraisal process.”

But it is not just appraisal bias which pushes a higher property tax burden on the backs of low-income people; politics plays a hefty role as well.

Raising property tax rates can come with political consequences for municipal leaders, particularly in a state where residents already face a substantial tax burden. For a number of municipalities, more accurate real estate appraisals would mean less money for local government and necessitate rate increases, creating a Catch-22 of political and financial problems.

A separate section of the same property tax analysis report found that if Hartford, for instance, were to accurately appraise low-value homes it would have to increase the mill rate to 116.09 just to keep city finances afloat.

Connecticut’s largest city, Bridgeport, is a prime example of the political conundrum.

Bridgeport was noted in the report as having one of the highest appraisal biases in the state, a whopping 56 percent over sale price.

But Kenneth Flatto, director of finance for the City of Bridgeport, says the numbers do not tell the whole story, and the report is missing a key piece of political information.

According to state law, municipalities are supposed to conduct a property revaluation every 5 years. However, Bridgeport went seven years without a property revaluation, after former mayor Bill Finch lobbied the state legislature and Gov. Dannel Malloy to allow Bridgeport a two-year extension.

Bridgeport conducted a real estate revaluation in 2008, just before the housing market crash, and didn’t conduct another valuation until 2015, after the legislature agreed to the two-year extension, putting Bridgeport one year beyond the scope of the analysis.

It also means Bridgeport residents – particularly those with low-value homes – paid taxes based on 2008 home values for two years longer when their homes were worth substantially less, costing low-income residents thousands in property tax payments. Finch argued the revaluation extension was necessary because Bridgeport had a high number of home foreclosures.

“Probably 10 to 20 percent of the population were out of whack” due to the old valuations, Flatto said. “High value homes recovered more quickly after the recession, but lower value homes did not.”

The scheduled revaluation of Bridgeport properties in 2013 would have led to significantly lower property appraisals and lower property tax revenue necessitating a significant mill rate increase to keep the struggling city afloat.

It wasn’t until Joe Ganim was elected mayor in 2015 that Bridgeport conducted a revaluation, resulting in $1 billion less in property tax revenue and forcing a tax increase of 29 percent.

Flatto says low-value home appraisals dropped more than average in the 2015 revaluation than high value properties. While many lower to mid-value homes saw a decrease in property taxes, owners of high-value homes saw taxes go up, according to the New York Times.

Bridgeport was not the only municipality to push off home valuations. Torrington also delayed its valuation until 2014. An article by the Torrington Register-Citizen describes one homeowner’s valuation dropping from $157,000 to $119,000, demonstrating the severity of 2008 housing market collapse.

Conversely, the report shows that higher value homes tend to be appraised more accurately, with some of Connecticut’s more wealthy suburbs showing the least amount of bias and, in some cases, under-appraising homes.

The report concludes that nearly 90 percent of municipalities show significant appraisal bias when valuing low-income homes, resulting higher effective mill rates for those homeowners.

Bob Zygmont

August 23, 2018 @ 12:07 am

After a corrupt revaluation in Greenwich in 2008, the tax burden on my mother’s modest 3BR ranch increased by 46%.

Prior to that, residents in “High Value” homes (Round Hill) commissioned a study of their tax rates.

Their consultant determined that they were paying approx. 12% more than they should.

That same consultant was hired by The Town of Greenwich to assist in their upcoming revaluation.

To nobody’s surprise, The Round Hill and other similar “High Value” properties tax burden decreased while more modest homes taxes increased substantially.

Your report comes as no surprise to me.

We have since moved to Pasco County, FL.

On her house with 1400SF 2BR, 2Bath, 2car garage. pool, canal waterfront, 0.44 acres Taxes under $600.00

On my house. 900 SF 2BR, 2 bath, 2 car garage, 0.10+ acres. Taxes $360.00

David Lucey

November 6, 2018 @ 5:24 pm

Interesting analysis, but leaves much unexplained. Are the data points in the chart by town and year? When you say “Group aggregate”, which group? Only single family or including apartments? Graphing all towns in one chart based on price is misleading as most towns in FF County don’t have houses for less than $500k so you muddy up the point you are trying to make. Which data is used for this analysis? A great opportunity to make data and code available to be reproduced and expanded upon. I work in R and have been looking at some of these issues as well as others pertaining to CT, and might be interested in contributing.