Cheryl Spano Lonis has been a nurse in Connecticut’s prison system for 19 years and a member of the New England Health Care Employees Union 1199. But when she tried to opt out of union membership in 2015 based on her religious beliefs and donate her union fees to charity, SEIU 1199 ignored her.

“I had joined my church again, and my beliefs didn’t coincide with what the union’s beliefs were,” Lonis said in an interview with Yankee Institute. “I gave all the correct information according to the contract. I sent certified letters to both the union and UConn Health, I called human resources to tell them I had sent the letters and they kept telling me they have to hear from the union.”

But the union never changed her membership status, according to Lonis, her pay stubs, emails from her employer and the Comptroller’s Office. Nearly $3,000 in dues and fees over three years was never sent to charity.

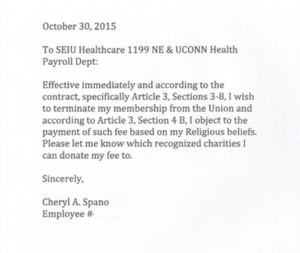

Certified mail receipts from October of 2015 show Lonis sent letters to both SEIU 1199 and her employer, UConn Health, informing them of her decision to opt out of the union based on her religious beliefs with a request that her fees be donated to charity.

According to the P-1 bargaining contract, “Employees objecting on religious grounds shall make a monthly contribution to a nationally recognized charity, designated by mutual agreement of the Employer and the Union, equivalent to Union dues and initiation fees.”

The right to object to union membership based on religious grounds and donate union fees to charity is outlined by the National Labor Relations Board as well.

According to the NLRB website, “You may object to union membership on religious grounds, but in that case, you must pay an amount equal to dues to a nonreligious charitable organization.”

In her letter to the union, Lonis requested a list of approved charities to which she could donate her fees, but never received a response.

Lonis followed up on her certified mail request in January of 2016, emailing UConn Health Payroll Supervisor Lynn Martin for help.

Martin acknowledged UConn Health had received Lonis’ October letter but said they could not make the change until they heard from the union. Martin forwarded Lonis’ emails to John Kiang, one of 72 organizers on SEIU 1199’s payroll, but by February nothing had been done.

“I have been advised by some woman at 1199 that I am not in the union back from October/November, yet they still take dues out,” Lonis wrote in the email dated February 1, 2016. “When I asked for an Amy to call me from there she never called me. Can you explain why this is taking so long? What will be [done] with the dues for that time that should have been donated to a charity?”

When there was no response from Kiang, Martin forwarded Lonis’ requests to UConn Health Principle Labor Relations Specialist Sylvia Santos-Flickinger.

Santos-Flickinger sent Lonis back to the union organizer. “I am copying John Kiang. You should contact him. Any changes in union dues will have to come officially from the union to payroll,” Santos-Flickinger wrote in an email. “You should direct your questions to him.”

Kiang never responded to the email, but Lonis says Kiang came to her workplace and spoke with her, asking why she wanted to opt-out. Cheryl cited her religious beliefs, but no changes were made and her dues were still not sent to a charity.

Lonis says her request to opt-out of the union was made known to the union delegate at her job.

“With our union delegate at the facility, it was kind of a running joke that ‘oh, yeah, you’re out of the union.’ But I said ‘you’re still taking dues out of my paycheck, it’s not converted to fees.’ They didn’t do anything about it.”

In recent emails between Lonis, the Comptroller’s Office and SEIU 1199 organizers Kiang and Rebecca Simonsen, the union claims Lonis opted out and is a nonmember, but deductions from Lonis’ paycheck — and the Comptroller’s Office — tell a different story.

According to the Comptroller’s Office which processes Lonis’ paycheck and deducts dues, Lonis has been a full dues paying member since 2003.

“The payroll system identifies her as a dues payer going back as far as 2003,” the Comptroller’s Office wrote in an email. “There are no changes indicated during that time.”

According to Lonis’ pay stub she was charged $36.46 for dues to the union, which would total $950.56 per year. Since her 2015 request, nearly $2,800 has gone to the union rather than a charity.

“I got tired of fighting the fight”

Lonis said she gave up after being continually turned back toward the union and Kiang in order to lodge her religious objections. “I just let it go,” Lonis said. “I got tired of fighting the fight.”

Reviewing Lonis’ contract at the time of her request, it is easy to see why — requirements the union placed on objecting members were prohibitive.

To become a nonmember required a certified letter to the union, but in order to pay a reduced amount employees also had to review the union’s financial statements, highlight the union’s objectionable spending and then have their objections heard by the union’s executive board. Otherwise they were forced to pay fees equal to the amount of dues.

Lonis says she was never given the opportunity to review the union’s financial statements and log her objections when she sent her request in 2015.

The union contract references Connecticut General Statute 5-280, which reads, “If an exclusive representative has been designated for the employees in an appropriate collective bargaining unit, each employee in such unit who is not a member of the exclusive representative shall be required, as a condition of continued employment, to pay to such organization for the period that it is the exclusive representative, an amount equal to the regular dues, fees and assessments that a member is charged.”

According to the Supreme Court’s 1977 decision in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, government union members could opt-out of membership and pay fees associated with collective bargaining costs, but could not be forced to contribute toward the union’s ideological or political causes.

According to the Comptroller’s Office “dues payers and fees payers pay the exact same amount of bi-weekly deductions,” despite their political or religious objections.

This is because unions claim that any political spending is financed through “separate, voluntary contributions,” supposedly through political action committees.

Regardless, the contract and the NLRB said Lonis could opt out based on her religious beliefs and forward her fees to an agreed upon charity. Even if SEIU 1199 believed she was a nonmember, they never honored her requests to forward her fees to charity.

As of 2017, New England Health Care Employees Union 1199 had 346 agency fee payers and 25,654 members, according to the union’s LM-2 statement — a tiny 1.3 percent of represented workers — who, according the Comptroller’s Office, paid the same amount in fees as union members paid in dues.

The union also recorded $931,976 in political spending and lobbying for that year.

But not all political work necessarily involves spending money. Unions have access to human and political capital as well, enlisting members as volunteers for rallies, protests, and throwing their support behind local, state and national political candidates.

SEIU 1199 is a stalwart political presence at Connecticut’s Capitol, their purple and yellow t-shirts and flags clearly visible at rallies and protests supporting or opposing a number of social issues — everything from immigration to a $15 minimum wage.

Unions’ fondness for Democratic candidates is well documented. During the 2016 election cycle SEIU spent more than $24 million supporting or opposing national candidates, almost all of the money going to Democratic candidates, according to Open Secrets.

In 2017, SEIU 1199 in Connecticut contributed $177,653 to SEIU’s Committee On Political Education fund in Washington, which is then used to fund political candidates across the country.

That, in and of itself, is unremarkable. It does, however, leave objectors like Cheryl Lonis in a difficult position.

Though she tried to lodge her religious objection, her request was either ignored or bungled, as the Comptroller’s Office never received word from the union to change her membership status.

A Supreme Court end to opting out

The Supreme Court’s recent decision in Janus v. AFSCME, however, puts an end to the opt out windows and the need to fight in order to have one’s objections heard.

According to the decision, members can resign from union membership without paying fees and continue to keep their jobs in state and local government.

The state of Connecticut immediately ceased collecting fees from nonmembers, which could result in $3.4 million per year less to unions representing state workers. The number of agency fee payers employed with local governments is more difficult to determine.

The results of the Janus decision were not surprising to union leaders. A similar case, Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association in 2016, resulted in a tied court following the death of Justice Antonin Scalia.

Anticipating the decision, unions renewed efforts to recruit and retain members through union card drives. The Supreme Court’s stipulation that newly hired state and municipal employees must affirmatively opt-in to union membership added another wrinkle to the decision.

State and local employees who never signed membership cards or whose paperwork was lost or mishandled still had fees deducted from their pay, technically making them nonmembers even if they supported the union, according to AFSCME Local 562 Vice President Merisa Williams in an interview with Connecticut Post columnist Dan Haar.

Lonis says leading up to the Janus decision, union organizers began showing more interest in workers, something she had not seen since she began her job nineteen years earlier.

“Just in the last few months since the Janus case went to the Supreme Court they began coming back into the facilities trying to get members, but to my mind it was already too late,” Lonis said. “Where were you all these years when you took our dues from us and we didn’t feel as important?”

Kristiander

February 9, 2020 @ 9:40 pm

In 2009, the phrase “taxation without representation” was also used in the Tea Party protests, where protesters were upset over increased government spending and taxes, and specifically regarding a growing concern amongst the group that the U.S. government is increasingly relying upon a form of taxation without representation through increased regulatory levies and fees which are allegedly passed via unelected government employees who have no direct responsibility to voters and cannot be held accountable by the public through elections.