Connecticut has made its full annual payment and reduced the discount rate for its pension plans, but according to a study by Pew Charitable Trusts the state is still not contributing enough to prevent pension liabilities from growing.

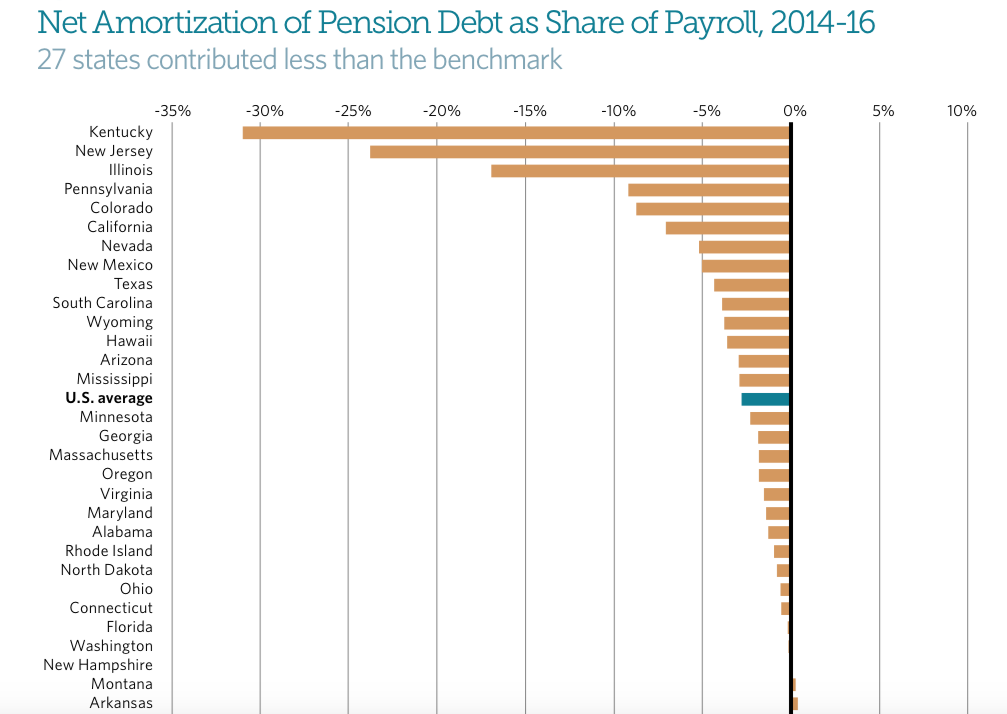

Connecticut was listed as one of twenty-seven states who saw their funding gaps increase between 2014 and 2016 due to interest on the debt, actuarial assumptions and the cost of benefits — known as “net amortization.”

Pew used data over the course of three years to give a better picture of how states’ pension funding gaps changed.

While Connecticut saw positive growth in 2015 and 2016, those figures were not enough to make up for a $169 million shortfall in 2014.

Although Connecticut was far from the worst for not meeting annual funding requirements, the state also has one of the most underfunded pension systems in the country, growing pension costs, a stagnant economy and severe fiscal difficulties, leaving little room for increased costs.

Connecticut was one of only five states whose pensions were less than 50 percent funded. According to Pew, Connecticut’s combined pension funds are only 41 percent funded.

New Jersey was the worst at 31 percent, while New York’s pension system was over 90 percent funded.

Pew’s researchers indicated that historically high discount rates have contributed to the funding lapse.

Connecticut recently lowered its assumed rate of return from 8 percent for the state employee retirement system to 6.9 percent and lowered the rate of return for its teacher pensions from 8.5 percent to 8 percent.

According to Pew, however, these rates are still too high.

Pew used a benchmark of 6.5 percent rate of return, noting that on average, states have only generated 6 percent over the past decade.

While Connecticut saw a spike in the return on its pension plan this past year due to strength on Wall Street, the pension plans only returned 6.2 percent for SERS and 6.22 percent for TRS between 2014 and 2016, according to the state’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report.

But lowering the discount rate results not only in a big decrease in the state’s funding ratio, but also increased annual costs for taxpayers because the state must contribute more toward the pensions.

Failure to set reasonable and realistic discount rates can lead to higher liabilities in the future. Pew writes “state plans generated just 6 percent returns over the past decade, and various projections suggest that returns will be around 6.5 percent a year for the next 10 years or longer.”