A bill authorizing the state of Connecticut to conduct a study on the viability of education savings accounts drew a bevy of experts and advocates to a packed public hearing before the Education Committee on Thursday.

Speakers from EdChoice, the Heritage Foundation, Reason Foundation, CT Parents Union, Connecticut Catholic School organizations and Yankee Institute argued the state should study ESAs as a way to save money and offer parents a choice in education.

Ashley DeMaura with the Foundation for Excellence in Education argued that ESAs can greatly benefit students with learning disabilities by allowing more flexibility in how their child is educated. “Parents decide where the best values are and can direct their child’s funds in the most efficient way.”

Education savings accounts allow a parent to use some of the money normally allotted for their child to attend their district public school for placement in an independent school, tutoring costs, online classes or special services.

ESAs have been used to varying degrees in states like Arizona, Florida and North Carolina.

Michael Griffin, superintendent of Catholic Schools for the Archdiocese of Hartford, said that parochial schools offer children the opportunity to receive a good education for less money per student that traditional public schools. Nevertheless, many working families cannot afford the out-of-pocket tuition costs and Catholic schools have been closing for financial reasons.

“The need for choice seems to be far greater than what the state can do on its own at this time,” Griffin told the committee. “That is why a study on the potential effects of educational savings accounts in Connecticut — which would apply to private and parochial parents and their children — is timely and necessary.”

The average cost per pupil in Connecticut’s public school system is $16,249. An ESA of $5,000 would allow a parent to pay tuition for a parochial school or other form of education, while the remaining $11,249 would still be paid to the public school to support their costs.

Connecticut’s public education system is widely considered one of the best in the country, except for pockets of failing schools and under-served kids largely located in Connecticut’s major cities like Hartford and Bridgeport.

The education gap has been the basis for several landmark lawsuits against the state and has led to a string of state efforts to improve student access to better schools, but the results have been disappointing.

The 1996 Sheff v. O’Neill Connecticut Supreme Court decision ruled that Hartford’s unintentional racial segregation of students — with minority students trapped in failing schools — was unconstitutional.

In response, Connecticut developed a magnet school system, which enrolls students based on a lottery and racial quotas.

But the changes have not satisfied the original plaintiffs in Sheff v. O’Neill and have led to another lawsuit by Hartford parents who claim the racial quotas are leaving empty seats in magnet school classrooms.

A lawsuit by the Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding, which argued that Connecticut’s school funding mechanism was unconstitutional was eventually shot down by the Connecticut Supreme Court, which ruled the state’s education funding formula should be left to the legislature to fix.

State funding for education will continue to be a hot-button issue as the state continues to face mounting budget deficits. Aside of fixed costs, education grants to municipalities are Connecticut’s largest expense, and also the only major expense lawmakers have much control over at this point.

Connecticut is projected to face a $4.6 billion deficit in the next biennium and tax revenue collections have been flat or, in some cases, declining. The 2017 SEBAC concessions deal included a no-layoff provision for state employees and locked in raises until 2022 and benefits until 2027, meaning lawmakers will have to find other ways to cut spending to fill the budget gap.

During the 2017 budget battle, Gov. Dannel Malloy zeroed out education funding for 85 school districts and severely cut funding to another 54 when he was forced to run the state through executive order.

The budget agreement eventually passed by the legislature largely held municipalities harmless, but school districts still face rising costs.

Directed to find $182 million in savings by the budget agreement, Malloy eventually cut $91 million in education funding to municipalities, shocking local leaders.

Connecticut also faces a growing crisis in its teacher pension system. The costs of teacher pensions is projected to grow from $1.2 billion per year to potentially $6 billion per year and represents one of the fastest growing state expenses.

Malloy attempted to bolster the teacher pension system by forcing municipalities to pay one-third of the teacher pension costs. The proposal was met with outcry from municipal leaders and organizations, who argued the extra costs would drive up property taxes to pay for the state’s mistakes.

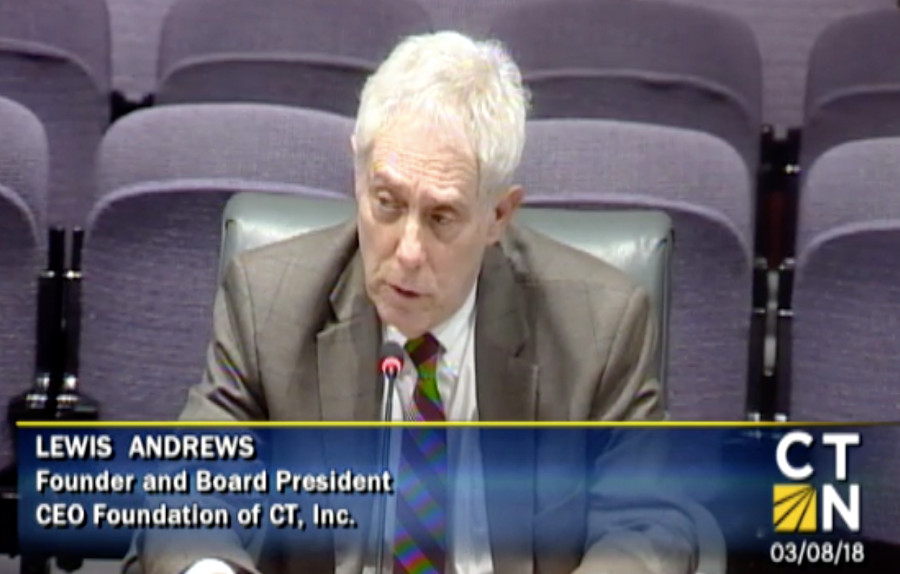

But Lewis Andrews, co-author of a 2017 study on the potential effect of ESAs in Connecticut, says education savings accounts could help meet the education needs of underserved kids and save Connecticut money.

“Parents could custom-tailor their children’s education with money not currently available,” Andrews told the committee. But he said the “real surprise” of the study was “the potential to bail out the state of Connecticut from its pressing fiscal problems.”

The study conducted by Andrews and Dr. Marty Leuken of EdChoice found the if only 2 percent of students utilized a $5,000 ESA the state could save $26 million per year and municipalities could save more than $50 million.

Andrews noted that with 10 percent enrollment, the savings roughly equal the amount of money Gov. Malloy tried to get municipalities to contribute toward teacher pension costs.

But representatives of Connecticut’s powerful teachers’ unions do not like the idea and Orlando Rodriguez of the Connecticut Education Association told the committee ESAs are an attempt to funnel money away from public schools and into religious or private schools.

Rodriguez said studies showing the effectiveness of ESAs were done by “partisan groups” and there have been no “academic” studies on the benefits or detriments of such a program. He then argued against the state of Connecticut conducting such a study.

Rodriguez read from a colleague’s testimony which claimed ESAs are an attempt to “further segregation” in schooling, and said failing urban schools need more state funding to hire more teachers.

But Gwen Samuel of the CT Parents Union says the committee should not look at ESAs as a political issue, but rather look at what is best for children and parents.

“You have to give the parents the means to help themselves help their children,” Samuel told the committee. “Please, let’s not make doing what’s right by children political,” Samuel said.