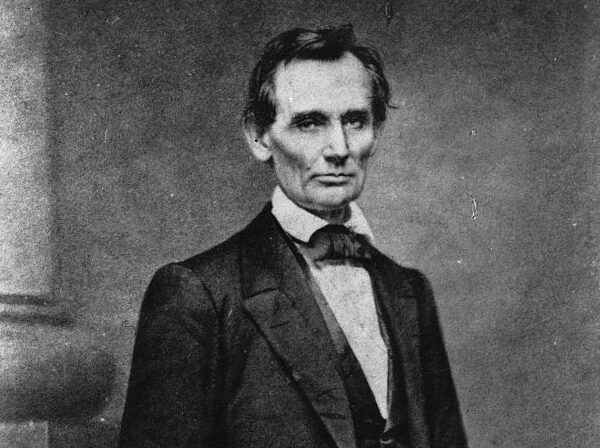

On Feb. 27, 1860, Abraham Lincoln rose to speak before a crowd of 1,500 — who trekked through the snow — at The Cooper Union, a newly established center for learning and civic discourse in New York City. The tall, lanky lawyer from Springfield, Ill., had been invited by “The Young Men’s Central Republican Union” and prominent state Republican party leaders to deliver a scathing condemnation of slavery’s expansion into the West via “popular sovereignty”: a policy promoted by Democrat Illinois Senator and presidential hopeful, Stephen Douglas, in which residents self-determined whether their territory would be admitted as a free or slave state.

The policy, solidified in the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854) introduced by Douglas, had ignited national anguish and bloodshed as “proslavery and antislavery activists flooded into the territories to sway the vote.” Hostilities were so severe that the affair had been called “Bleeding Kansas,” thrusting the nation closer to civil war. Indeed, the Republican Party formed in response to the act and slavery’s promulgation.

Two years prior to Lincoln’s New York speech, he sparred with Douglas in a series of debates on slavery, popular sovereignty and other national issues during the 1858 campaign for the U.S. Senate. By that time, his political career on the federal level had been limited to only one term in the U.S. House of Representatives, from 1847-1849. (During his tenure, he introduced legislation to abolish slavery in Washington, D.C.) Yet he gained a notable, honest reputation and became a well-regarded orator between then and the 1858 election.

Ultimately, he lost to Douglas, but the debates “propelled Lincoln’s political career into the national spotlight,” according to American Battlefield Trust. While he was discussed as a possible Republican presidential candidate for the 1860 election, the Cooper Union address was a test to see whether his message would resonate with Northeastern Republicans, whom he desperately needed to secure the nomination.

The speech altered his life and political prospects — and he would present a similar oration in the following days throughout New England, including his five appearances in Hartford, New Haven, Meriden, Norwich, and Bridgeport from March 5-10, 1860.

This is the story of how Lincoln’s time in Connecticut helped solidify his candidacy for president.

‘You Have a Special Call There’

Lincoln’s Cooper Union speech was a two-hour, rousing call not so much for slavery’s abolition, but for its restriction, bearing thematic resemblances to his “House Divided” address at the Illinois Republican State Convention in 1858. Weaving through Constitutional history, as well as criticizing the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, the Springfield lawyer exclaimed:

“This is all Republicans ask — all Republicans desire — in relation to slavery. As [the Founding Fathers] marked it, so let it be again marked, as an evil not to be extended, but to be tolerated and protected only because of and so far as its actual presence among us makes that toleration and protection a necessity. Let all the guarantees those fathers gave it be, not grudgingly, but fully and fairly, maintained. For this Republicans contend, and with this, so far as I know or believe, they will be content.”

Though vehemently opposed to slavery, even from the beginning of his public career, Lincoln did not argue for emancipation lest it destroy the Union. The Springfield lawyer also distanced the Republican Party from John Brown’s raid of Harper’s Ferry in Virginia, fearing that a general voting populace would associate the party with radicalism. Nevertheless, he told attendees to “have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

The speech was immediately popular. Connecticut Republican State Chairman Nehemiah Sperry and other Republican groups asked Lincoln to give speeches in the Constitution State to boost Republicans, like gubernatorial candidate and incumbent William Buckingham, ahead of the April 2, 1860, election. The election was “especially important,” as noted by Michael Burlingame in Abraham Lincoln: A Life, “for Democrats believed that their popular candidate, Thomas Seymour, could capture the governorship, thus breaking the Republican hold on New England and inspiring Democrats everywhere.”

Lincoln consented, but he would do so after visiting his son, Robert, at Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire.

James A. Briggs, an Ohioan attorney and a friend of Lincoln’s, recognized the importance of a tour in Connecticut, writing in a Feb. 29 letter, “You have a special call there, & a duty to perform.” Similarly, Edward H. Rollins, a notable New Hampshire Republican and later U.S. Senator (1877-1883), told the rising star in a March 2 letter, “I certainly think that the Connecticut people need you more & have more right to claim you,” adding, “Connecticut is suffering.”

Initially, Lincoln was to stop in Hartford on March 2; however, he “received so many requests for speaking engagements in the Granite State that his address in Hartford was postponed until March 5,” according to Abraham Lincoln’s Classroom, a Lehrman Institute project. However, even prior to his arrival in Connecticut, an exhausted Lincoln wrote to his wife, Mary Todd, on March 4 from Exeter, N.H.:

“I have been unable to escape this toil — If I had foreseen it I think I would not have come East at all. The speech at New York, being within my calculation before I started, went off passably well, and gave me no trouble whatever. The difficulty was to make nine others, before reading audiences, who have already seen all my ideas in print —”

Lincoln, however, kept his engagements and soldiered on. He arrived in Hartford in the late afternoon to much fanfare from “enthusiastic Republicans” and the Hartford Cornet Band. He even found time to mosey up Asylum Street to Brown & Gross, a bookstore, where he met Gideon Welles, editor of the Hartford Evening Press. The two quickly became friends, and held each other in high esteem, so much so that Lincoln named Welles Secretary of the Navy the following year.

That evening, Lincoln was accompanied by several Republican dignitaries, including Buckingham, to Hartford City Hall. His speech was essentially the same one presented at the Cooper Union, albeit with slight modifications. With vigor (and even humor sprinkled throughout the speech), Lincoln told the crowd:

“If slavery is right, it ought to be extended; if not, it ought to be restricted — there is no middle ground. Wrong as we think it, we can afford to let it alone where it of necessity now exists; but we cannot afford to extend it into free territory and around our own homes. Let us stand against it!”

Reviews were mixed, at least between the Hartford Courant and Hartford Times. The former praised Lincoln for making the “most convincing and clearest speech” residents “ever heard made”; meanwhile, the latter “tried to put the worst possible light on the event,” highlighting the speaker’s “slovenliness” and overall message. However, Lincoln’s “down-to-earth style and appearance pleased his audience, which regarded him as a true man of the people,” according to Burlingame.

Afterwards, a crowd escorted Lincoln, many of them young adult men associated with the Wide Awakes, a Republican political organization, to Hartford mayor, Thomas Allyn’s home. There, a tired Lincoln slept.

‘In Which He Can Better His Condition’

The next day, March 6, Lincoln toured the Sharps Rifle Works and Colt Armory, then headed to New Haven, where he would speak at then-Union Hall (now Vanderbilt Hall) at Yale. He had been invited by James F. Babcock, editor of the Palladium, a local newspaper, and John D. Candee, a Yale alumnus, class of 1847.

The enthusiasm was palpable. The Palladium reported that “The hall was literally jammed” and “Every seat was packed full” to hear him. Toward the beginning of his speech, Lincoln acknowledged slavery’s absence in Connecticut and New England, telling his audience, “To us it appears natural to think that slaves are human beings; men, not property,” and that the Declaration of Independence “applies to the slave as well as to ourselves.”

Still, like in the Cooper Union speech and prior addresses on the tour, Lincoln expressed a steadfast, yet rational approach to restricting slavery’s expansion into the West, epitomized by a metaphor he had only employed days earlier in New Hampshire, according to Burlingame:

“If I saw a venomous snake crawling in the road, any man would say I might seize the nearest stick and kill it; but if I found that snake in bed with my children, that would be another question. I might hurt the children more than the snake, and it might bite them.”

Yet Lincoln prophesied that the nation could not avoid the slavery question any longer. In fact, “Slavery is the question,” he stressed. It stood in the way of “giving of necessary attention to other questions of national house-keeping.” Nevertheless, Lincoln could not resist interspersing commentary between the slave-trade and the ongoing ‘Shoemakers’ Strike,’ which was the largest labor strike in the nation in the antebellum years. Across 25 towns in New England, more than 20,000 shoemakers walked off their jobs due to low wages on George Washington’s birthday, Feb. 22, 1860.

In a true show of logical reasoning, the Springfield lawyer did not bemoan the laborers’ course of action, but sided with them, saying, “I like the system which lets a man quit when he wants to, and wish it might prevail everywhere,” adding:

“One of the reasons why I am opposed to Slavery is just here. What is the true condition of the laborer? I take it that it is best for all to leave each man free to acquire property as fast as he can. Some will get wealthy. I don’t believe in a law to prevent a man from getting rich; it would do more harm than good. So while we do not propose any war upon capital, we do wish to allow the humblest man an equal chance to get rich with everybody else. When one starts poor, as most do in the race of life, free society is such that he knows he can better his condition; he knows that there is no fixed condition of labor, for his whole life. I am not ashamed to confess that twenty five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat — just what might happen to any poor man’s son! I want every man to have the chance — and I believe a black man is entitled to it — in which he can better his condition — when he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him! That is the true system.”

Attendees erupted in applause throughout the speech. The Palladium reported, “For several minutes, everybody was cheering.” Like in Hartford, residents journeyed with Lincoln to his lodgings, this time at Babcock’s house, begging for more words (though whether he obliged was unreported).

On Wednesday, March 7, Lincoln took a day trip to Meriden, speaking to 3,000 at the town hall. While he gave a similar speech as the previous days, a heckler interrupted him “asking whether the Republicans would be able to inaugurate a president if they should win the November election,” according to Burlingame. Lincoln, undeterred and quick-witted, responded, “I reckon, friend, that if there are votes enough to elect a Republican President, there’ll be men enough to put him in.”

Over the next few days, he stopped in New London for a three-hour stay, giving no remarks, then headed to Providence and Woonsocket, R.I. On March 9, Lincoln returned to Connecticut, speaking to an audience at Norwich’s town hall, receiving much of the same adulation as in prior events, as well as some detractors, who called him an electoral loser. However, as the Norwich Bulletin reported:

“Mr. Lincoln was received upon his entrance into the hall with storms of applause, loud and prolonged, and when he was introduced by Mr. Lamb, the enthusiasm of the audience knew no bounds. Some minutes elapsed before the applause subsided sufficiently to allow him to commence his address.”

He spent the night at the Wauregan House (which exists to this day, but as apartment buildings). The next day, March 10, Lincoln finished his Connecticut tour in Bridgeport. That evening, he spoke at Washington Hall, a lecture room in the Fairfield County Courthouse. According to the Bridgeport Library’s History Center, a local newspaper described him as a “tall, bony, angular, big jointed figure with a great towering head and very expressive countenance,” adding that he conveyed “intellectual power.” However, no record of his speech survives — though one can surmise it was a modification of the Cooper Union address.

Lincoln did not stay in Bridgeport after the speech’s conclusion, electing to head back to New York City. It was the final appearance he made not only in Connecticut, but New England.

‘He Belongs to the Ages’

After a brief stay in New York City, a travel-weary Lincoln returned home to Springfield. All the miles travelled and speeches given in New England proved to be a success.

In the ensuing months, Buckingham was re-elected Governor of Connecticut by a little more than 500 votes — though how much credit belongs to Lincoln’s speeches is uncertain. Still, Lincoln was “delighted” by the victory, according to Burlingame. Gov. Buckingham would be a critical ally when Lincoln assumed the presidency, mustering and equipping men to fight for the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Meanwhile, Lincoln — who seldom openly expressed his ambition for the nation’s highest office — confessed to Lyman Trumbull, a Springfield lawyer and friend, in an April 29 letter that the “taste is in my mouth a little,” though quickly adding, “this, no doubt, disqualifies me, to some extent, to form correct opinions.” Weeks earlier, on March 24, he also admitted to Samuel Galloway, an Ohioan lawyer, “My name is new in the field; and I suppose I am not the first choice of a very great many.” Yet he did not want to lambast other possible nominees like Sen. William Seward of New York and Salmon Chase, former governor of Ohio. Instead, his “policy, then, is to give no offence to others — leave them in a mood to come to us, if they shall be compelled to give up their first love.” (Indeed, during Lincoln’s presidency, Seward served as the U.S. Secretary of State and Chase was Secretary of the Treasury, then appointed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.)

For one who actively sought the Republican nomination, Lincoln’s tour brought him a “new stature and attracted a horde of presidential supporters,” according to Burlingame. As he writes in Abraham Lincoln: A Life:

“In New Haven, Lincoln was so impressive that the editor of the Palladium, James Babcock, endorsed him for the presidency and persuaded two delegates to the national convention to vote for him. …After his talk in Norwich, Lincoln and local Republican leaders conferred at the Wauregan Hotel, where one gentleman suggested that their guest of honor might be a candidate for vice president. ‘Sir,’ interjected Amos W. Prentice, ‘we want him at the other end of the Avenue.’ This remark elicited long and loud applause.”

However, Lincoln was still a dark horse candidate when the 1860 Republican Convention began at The Wigwam, May 16, in Chicago, Ill. A majority of Connecticut’s 12 delegates favored Edward Bates of Missouri in the first ballot for the presidential nominee. Bates received seven votes; Lincoln only two. By the end, after Lincoln already acquired a majority by the third ballot, Gideon Welles — one of the state’s delegates — announced a shift in votes, telling the convention that Connecticut went “8 for Abraham Lincoln, 2 for Salmon P. Chase, the rest as before given.”

Welles — originally a Chase supporter — travelled to Springfield to notify and congratulate Lincoln on his nomination. Meanwhile, the Hartford Courant (May 23, 1860) praised the Republican nominee’s victory, stating:

“Lincoln, in every sense, is one of the people, and the thinking, reading people, who know his antecedents and what he has struggled with, ratify his nomination with enthusiasm. Our opponents gain nothing by sneering at him, as a self-made man. It is a recommendation for him among all true patriots and lovers of the freedom which our institutions give to the rise of man. …From the time when he split rails to fence his mother’s land, to the time when he stands as the nominee for the Executive of a free people, his life has been a successful struggle. All this labor and toil, this perseverance and energy, this self-reliance and self-education, have the better fitted him to govern others.”

In the end, Lincoln won the presidency in November against John Breckinridge; Southern states seceded from the Union; and Americans were catapulted into the “deadliest” war in U.S. history. Arguably, Lincoln is often considered the greatest president ever, rivalling George Washington, for leading the nation through its most tumultuous time, as well as for issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, which “forever” freed all slaves in the rebellious states, thus leading to abolition for the entire nation after the 13th Amendment’s ratification on Dec. 6, 1865.

Lincoln, however, would not live to see the amendment’s adoption or shepherd the nation — with “malice toward none and charity for all” — after the Confederacy’s surrender at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia, April 9, 1865. He would be assassinated by Southern sympathizer and actor, John Wilkes Booth, while attending a play at Ford’s Theater, April 15. In the mayhem, Lincoln was rushed across the street to the Petersen House, where he eventually died. By his bedside, in a fitting, succinct eulogy, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton stated, “Now he belongs to the ages.”

Indeed, Lincoln does belong to the ages. He is the American story: born into poverty, turned into a self-made man, and then, through sheer will and adhering to the principle that all men are created equal, rose to the highest office in the nation. No doubt, he oriented the country’s heart toward justice that still reverberates to the present. As Burlingame writes, “Lincoln’s remarkable character helped make him not only a successful president but also a model which can be profitably emulated by all.”

Lincoln is worthy of praise and emulation. And Connecticut should be prideful that it provided the space for this great American to not only hone his statesmanship and anti-slavery message, but that the public became more conscious of his ability to serve as president while touring the Constitution State. That is a truth we should treasure.

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler

A personal note: Typically, young boys might have posters of superheroes or famous athletes plastered over their walls. For me, George Washington and Abraham Lincoln posters adorned my bedroom. I was fascinated by both presidents, but, regarding the latter, I would often draw pictures of Lincoln — or in my clumsy toddler speech, ‘Hebraham Blinkon’ — for my teacher, Ms. Kate Nolan. During my high school graduation, Ms. Nolan gifted me a copy of one of those drawings, though she kept the original because she still believes it might be worth something one day. That remains to be seen. Nonetheless, the reason I’m sharing this anecdote is that Lincoln had a profound impact on my upbringing and outlook on America and, indeed, life. My hope is that we who carry the torch of liberty today keep him as a role model.

What neat history do you have in your town? Send it to yours truly and I may end up highlighting it in a future edition of ‘Hidden in the Oak.’ Please encourage others to follow and subscribe to our newsletters and podcast, ‘Y CT Matters.’