In February 1839, Sengbe Pieh was working in the rice fields of Mendeland — or present-day Sierra Leone, a nation on Africa’s west coast. The nearly 25-year-old farmer and trader was a family man, with a wife and three children. He had never left his home country.

Yet more than 400,000 people from the region had left — albeit forcibly and brutally, as the slave trade, as early as the 15th century, wrought its heinous terror, capturing and transporting Africans to European colonies in the Caribbean and North America. By 1807, Great Britain outlawed the transatlantic slave trade after an abolitionist campaign spearheaded by William Wilberforce; the United States, Spain and Portugal banned the practice in 1808, 1817 and 1836, respectively.

However, illegal activities did not stop. Pieh, along with “countless others,” was abducted in the rice fields by Portuguese slave hunters, taken to Lomboko — a slave-trading factory where he was incarcerated — and sold into slavery. With more than 50 men and women and four children, Pieh was purchased by two Spanish plantation owners, Pedro Montes and Jose Ruiz, and boarded the schooner, La Amistad, on June 28, 1839. Its destination: Camagüey, Cuba, then a Spanish colony.

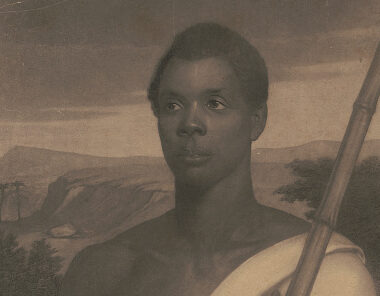

In truth, Pieh — later known as Joseph Cinqué — would never reach the Cuban plantations to which he was headed. For nearly two years, he would fight for his own freedom, as well as for other would-be slaves on La Amistad, before Connecticut state judges and the U.S. Supreme Court, with former U.S. president John Quincy Adams serving as one of his defense attorneys.

The defense of his inalienable rights and escape from lifelong servitude marked one of the most consequential episodes in the U.S. abolitionist movement in the years prior to the American Civil War (1861-1865).

This is the story of La Amistad.

Death of Capt. Ferrer

Translated from Spanish, “Amistad” means friendship, but there was nothing of the sort between captors and the enslaved on the schooner. Most prisoners were kept below deck in the “dark, stuffy, cramped hold for long hours at a time, in a painful crouch, enveloped by, and themselves exuding, the sharp odor of bondage,” according to The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom by Marcus Rediker. Meanwhile, apart from receiving poor food and water rations, the Spanish captors inflicted violent discipline on the Africans with any tool at their disposal. In one episode, Cinqué was hit with a plantain by the ship’s cook.

The atmosphere was ripe for an all-out conflict — and it swiftly came. On a moonless night, July 2, 1839, several days after leaving Havana, Cinqué and several others “managed to break a padlock,” found bludgeoning objects and machetes, and attacked Capt. Ramón Ferrer, slashing him to death, according to Rediker. The cook, who reprimanded Cinqué, was also killed in the ensuing mayhem.

Within a few bloody moments, Cinqué and the others, bound for slavery, took La Amistad and their would-be owners, Ruiz and Montes, captive. However, as Redicker describes, the freed group faced an immediate problem — “they wanted to return to their homes in southern Sierra Leone, but none of them knew how to navigate the schooner.” The Africans, dead in the water, thus relied on their prisoners to sail them back home, across the Atlantic.

During the day, Montes followed orders; but when night fell, he “steered the vessel back to the west and the north” in the hopes of being “intercepted and saved” by another ship, Redicker notes. Cinqué and the others were unaware of Montes’ deception. In late August, Montes achieved his goal: La Amistad was spotted and seized by the U.S. brig Washington, commanded by Lt. Thomas Gedney, near Long Island, N.Y. Upon seizure, the American officer, assuming the schooner was a pirate ship, freed Montes and Ruiz and imprisoned the Africans once again in the cargo hold. The Washington then dragged La Amistad to New London, Conn.

After escorting the schooner to Connecticut, Gedney claimed salvage rights for not only the ship, but the Africans. Moreover, he “went ashore to send an express message to Judge Andrew Judson of the district court in New Haven, notifying him of the crimes of piracy and murder that had, in his view, been committed,” according to Redicker.

Judson was not sympathetic to the plight of blacks. Throughout his political career, he had been more-or-less a white supremacist. In 1831, he led an opposition campaign against the establishment of a black college in New Haven. Two years later, he orchestrated the passage of Connecticut’s “Black Law” to prevent Prudence Crandall — an abolitionist, Canterbury school teacher and, today, the official state heroine — from educating African American girls.

He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1835, but the following year, President Andrew Jackson appointed him to serve as a federal judge.

After multiple hearings, Judson — surprisingly, the first of several in the saga — did not immediately “authorize the sale of the slaves in the free state of Connecticut,” according to John Quincy Adams: Militant Spirit by James Traub. Instead, Cinqué and the other Africans would stand trial for murder and piracy, beginning Sept. 17, 1839, in Hartford. Until then, the Africans were held in a New Haven prison.

In the ensuing days, the “abolitionist community had mobilized around the fate of the Amistad captives,” notes Traub. Several formed the Amistad Committee — including Lewis Tappan, Joshua Leavitt and Simeon Jocelyn — to raise funds for the Africans’ legal defense. Former U.S. president John Quincy Adams, a known abolitionist, was approached for legal advice, which he readily gave. But no one could converse with the prisoners, which posed a nearly impossible challenge for the defense team. Nevertheless, Josiah Gibbs, a philologist from Yale University, tirelessly sought “New York waterfronts for anyone” who spoke Mende, and miraculously found an interpreter, 14-year-old James Covey.

Meanwhile, the Amistad quickly became a national story, with the press turning Cinqué into a martyr and, as Traub describes, “one of America’s first black heroes.”

Concurrently, the case caught the attention of Spain’s foreign minister, who threw the United States into an international legal quagmire. According to Connecticut History, the minister demanded the return of the Amistad, the Africans, Ruiz and Montes, and the ship’s cargo, claiming they were Spanish property, otherwise the seizure violated Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795. In response, Secretary of State John Forsyth — a Georgia resident and slaveholder — clarified that any intervention between the federal and state jurisdictions or the Executive Branch and Judiciary Branch breached separation of powers. In other words, President Martin Van Buren could not interfere in the proceedings for the time being. Yet the administration did not want to break the treaty.

Throughout it all, Redicker surmises Cinqué and Africans must have felt disoriented, as the fate of their lives hung in the balance. The New Haven jail cell offered conditions comparable to the Amistad’s cargo hold. To make matters worse, due to the story’s publicity, many outsiders — both supporters and opponents — visited the prison in droves to catch a glimpse of the exotic mutineers.

A Great Excitement

On Sept. 19, 1839, the Amistad captives’ murder trial began. Judge Smith Thompson, a U.S. Supreme Court justice, presided. Cinqué and the others were represented by Roger Sherman Baldwin, grandson of Roger Sherman, who had signed “all four of the most significant documents” in America’s early history, including the Continental Association, the Declaration of Independence, Articles of Confederation and the U.S. Constitution.

The case, however, had a tangled web of issues. According to Redicker, Judge Thompson had to adjudicate:

“…first and foremost whether the Africans were to be tried as pirates and murderers. Then came salvage claims by Lt. Gedney and other naval officers; salvage claims by Long Island hunters Henry Green and Peletiah Fordham; claims by Ruiz and Montes for their slave property; claims by the Spanish consul on behalf of the family of Ferrer for the schooner and enslaved cabin boy Antonio; and a request by the federal government that all property, both vessel and slaves, be returned to Spain.”

Baldwin’s argument ultimately rested on the fact that the Africans had been born free persons, which negated most — if not all — the legal questions. After two days of hearings, Judge Thompson dropped the murder and piracy charges since “he had determined that the United States had no jurisdiction over a crime allegedly perpetrated against Spanish citizens on the high seas,” as Traub notes. However, the issue of whether the Africans were property remained unresolved. He ordered the case’s resumption in November.

The judge also denied Cinqué and his Amistad compatriots a writ of habeus corpus, so they remained imprisoned through the intervening weeks.

On Nov. 19, the second trial commenced, this time with Judge Judson presiding, and held in both Hartford and New Haven, the latter after hearings spilled into the following year. Meanwhile, Secretary Forsyth, believing Judson would rule in the Spanish’s favor, had instructed a U.S. navy ship to “deliver the Mende” as “soon as the judge decreed their return to Cuba,” according to the National Archives. President Van Buren agreed, sending the U.S.S. Grampus to Connecticut.

Yet President Van Buren and Forsyth, as well as other non-abolitionists, were in for a shock. On Jan. 8, 1840, Cinqué — and two others, Grabeau and Fuli — testified by speaking through Covey. The prisoners’ leader acted out his “abduction in Africa, the deadly passage across the Atlantic, and the sale of the captive Mende in Havana.” In one instance, Cinqué shared that he killed the Amistad’s cook because the Spaniard threatened to eat them. However, the defendants needed to convince Judge Judson of their clients’ African origins; and they did. On Jan. 13, the judge affirmed Cinqué and his companions were “each of them Natives of Africa and were born free and ever since have been and still of right are free and not slaves.”

Redicker suggests Judson may have been persuaded — or pressured — by public sentiment and outcry in the Africans’ favor; nevertheless, despite the legal victory, the trials were not over since the U.S. government appealed the decision. As Traub attests, President Van Buren “had no wish to open a breach with Spain” and could not “afford to jeopardize his Southern support on the eve of the 1840 election by countenancing the right of people taken in slavery to commit conspiracy, insurrection, and homicide against their white captors.”

With the appeal, the Africans’ freedom was snuffed out. They were, once again, incarcerated, waiting for a final decision on their fates. The wait would take nearly another year.

Setting All the Captives Free

In April 1839, the Connecticut circuit court affirmed Judge Judson and the district court’s decision: the Amistad captives were African natives and, therefore, free persons. Yet the U.S. government, still fearing diplomatic ramifications with Spain, appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

At the time, Roger Taney — who freed his inherited slaves yet rendered the infamous Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) opinion — served as the court’s chief justice. There was no guarantee of legal victory for Cinqué and his companions, though Judge Thompson, who presided over the trial in April, sat on the bench along with another Connecticut native, Henry Baldwin. There was also legal precedent against them. In an eerily similar case, Antelope v. the United States (1825), the Supreme Court ruled that a captured Spanish slave ship’s cargo — including the human cargo — had to be returned to their ‘owners.’

The wait, however, began taking its toll on the imprisoned Africans. According to Redicker, Cinqué had been losing weight, constantly — and anxiously — inquiring about the next legal steps; and by the time of the Supreme Court case in January 1841, only 35 of the original 50-plus Amistad captives were alive. The rest died on the high seas or in jail.

But the Amistad Committee carried on valiantly in the hopes the Africans would be freed. Yet, as Traub describes, the committee “did not need a gifted lawyer” since Baldwin honorably represented the Amistad captives, but, instead, “needed a man of national stature who could present to the justices a vision of American national interests more morally compelling than the one the government would deploy in arguing to honor the terms of the treaty with Spain.” They turned to the septuagenarian, John Quincy Adams.

Adams was an abolitionist, and he followed the Amistad trial with keen interest. Now serving as a congressman in the U.S. House of Representatives, still the only former president to do so, Adams demanded in a resolution that President Van Buren “provide the diplomatic and official papers touching on the Amistad,” according to Traub. The resolution passed. Adams subsequently called for the Africans’ release, arguing that their “ongoing detention as unlawful,” but the resolution went nowhere.

Despite arguing before the Supreme Court in the past, Adams was hesitant to defend the Amistad captives, believing he was “too old, too busy, and too inexperienced for the job,” Traub states. However, as the U.S. National Park Service suggests, the former president “eventually took the case believing it would be his last great service to the country.” In truth, he feared failure. As Traub recounts, Adams “worried constantly” throughout his preparations for he understood the stakes and significance of the outcome in relation to future emancipation.

It might not have helped his nerves, as well as the Amistad Committee and the Africans’ well-being, when the court date was delayed from Jan. 16, 1841, to late February. However, after nearly two years since Cinqué and the Africans were enslaved, opening arguments commenced on Feb. 22. U.S. Attorney General Henry Gilpin contended that, under the Treaty of 1795, the Africans were considered Spanish property and thus must be returned. The following day, Baldwin asserted the Africans “were de facto free” when Lt. Gedney seized the Amistad, and that his clients were not the pirates, as initially charged, in the matter — the true pirates were Ruiz, Montes and Capt. Ferrer. The Spaniards violated law by engaging in the transatlantic slave trade; therefore, Cinqué and the Africans deserved freedom. As he stated:

“But they were not pirates, nor in any sense hostes humani generis. Cinque, the master-spirit who guided them, had a single object in view. That object was — not piracy or robbery — but the deliverance of himself and his companions in suffering, from unlawful bondage. They owed no allegiance to Spain. They were on board of the Amistad by constraint. Their object was to free themselves from the fetters that bound them, in order that they might return to their kindred and their home. In so doing they were guilty of no crime, for which they could be held responsible as pirates.”

Then, on Feb. 24, Adams’ opportunity to speak arrived. As Traub describes, the elder statesman — despite more than five decades of public service as president and as the nation’s foremost diplomat — was anxious and overprepared. However, he laid into the Van Buren administration’s correspondence with the Spanish government, and how “all this sympathy” was:

“…extended to the two Spaniards from Cuba exclusively, and utterly denied to the fifty-two victims of their lawless violence? By what right was it denied to the men who had restored themselves to freedom, and secured their oppressors to abide the consequences of the acts of violence perpetrated by them, and why was it extended to the perpetrators of those acts of violence themselves?”

Aside from scrutinizing the U.S. government’s arguments, Adams urged the justices to adhere to the inalienable rights enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, the nation’s founding document. Indeed, he literally pointed to copies of it displayed in the courtroom. This was not a cheap legal tactic Adams invoked to persuade hearts and minds. For him, it was not abstract. As a boy and teenager, he lived through the American Revolution, witnessing the Battle of Bunker Hill and even his father, John Adams, serving as a diplomat in France during the war. He saw the toll and struggle of war. Men sacrificed their lives for those principles. As he expounded:

“I will not here discuss the right or the rights of slavery. … That it is utterly incompatible with any theory of human rights, and especially with the rights which the Declaration of Independence proclaims as self-evident truths. The moment you come, to the Declaration of Independence, that every man has a right to life and liberty, an inalienable right, this case is decided. I ask nothing more in behalf of these unfortunate men, than this Declaration.”

He ended his oral arguments appealing to the justices’ Christianity, saying, with tears streaming down his cheeks, “I can only ejaculate a fervent petition to Heaven, that every member of it may go to his final account with as little of earthly frailty to answer for as those illustrious dead, and that you may, every one, after the close of a long and virtuous career in this world, be received at the portals of the next with the approving sentence — ‘Well done, good and faithful servant; enter thou into the joy of thy Lord.’”

Nearly all of the justices were persuaded. On March 9, in a decision delivered by Justice Joseph Story, the Supreme Court sided with the Africans, 7-1, writing, “There does not seem to us to be any ground for doubt that these Negroes ought to be deemed free.” Only Justice Henry Baldwin dissented. With the verdict, Cinqué and the Africans were officially free.

A Homecoming

After the verdict, Adams joyously announced to the Amistad Committee, “The captives are free!” However, freedom had several unresolved issues, most importantly whether Cinqué and the Africans would return to Sierra Leone. They were grateful for the legal victory, but, as Redicker indicates, they were “wary and subdued” since they “remembered their previous disappointment more than a year earlier, when they thought they had won their freedom.”

Meanwhile, Amistad Committee members sued Stanton Pendleton, a jailer, for the release of several of the Amistad girls who he employed “as servants in his kitchen” yet “provided neither domestic training or education,” according to Redicker. The bid was successful, as the court ordered the girls’ removal and placed them in the custody of abolitionist Amos Townsend.

In the end, the 35 surviving Africans elected to return home. However, as History.com explains, “the Supreme Court cleared the U.S. government of any repatriation duties, and new President John Tyler declined to provide funds of his own accord.” In short: the Amistad Africans would have to pay for their own voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. To fundraise, they toured New England cities and towns with the Amistad Committee organizing the events.

On Nov. 25, 1841, Cinqué and the Africans, along with five Christian missionaries, boarded the Gentleman. By January, the Africans landed back home; when they did, they became “transoceanic symbols of insurrection against bondage,” according to Redicker. However, the homecoming may have been bittersweet as most “vanished from the historical record,” including Cinqué who may have never reunited with his family. (The National Park Service suggests his family “perished during an ongoing war.”)

Yet, their actions — and fortitude — “reverberated powerfully throughout the United States,” as Redicker notes. The Amistad Africans had become cultural icons, bringing widespread national sympathy and attention toward the antislavery cause from a “variety of people who supported” the prisoners, but “insist[ed] that they were not abolitionists,” according to The Amistad Rebellion.

Today, the Amistad trial is considered one the more important milestones in shaping and growing the abolitionist movement, eventually leading to the collapse of slavery in America. Perhaps modern Americans more so know the events because of director Steven Spielberg’s movie, “Amistad” (1997); or, for Connecticut residents, they may have strolled the deck of a replica docked in New Haven or they are aware of Amistad Academy.

To think Connecticut was central in this international story is worthy of reflection. The Constitution State served as a crucible for the human rights debate in our nation’s history: though “all men” are endowed with such rights — life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness — they are never guaranteed. Our rights, and our neighbors’ rights, must be boldly protected. As John Quincy Adams rightly preached, history — and God — will judge those who stand aside and do nothing when one’s rights are threatened and/or infringed.

Let us resolve then to remember the courage of the Amistad Africans, and the abolitionists’ pursuit of the gift every man, woman and child deserves: freedom.

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler

What neat history do you have in your town? Send it to yours truly and I may end up highlighting it in a future edition of ‘Hidden in the Oak.’ Please encourage others to follow and subscribe to our newsletters.