Connecticut’s public elementary and secondary school per pupil spending hit a record high of $24,453 in fiscal year (FY) 2022, according to the Census Bureau’s latest Annual Survey of School System Finances. This puts Connecticut as the fifth highest in the nation, including the District of Columbia.

New York leads the nation in per –pupil spending at $29,873, followed by the District of Columbia ($27,425), New Jersey ($25,099) and Vermont ($24,608). Conversely, Utah spends the least per pupil at $9,552, with Idaho ($9,670), Arizona ($10,315), Oklahoma ($10,890) and Mississippi ($10,984) rounding out the bottom five.

According to the report, national per pupil spending increased by 8.9%, rising from $14,358 in FY 2021 to $15,633 in FY 2022. This marks the largest percentage increase in over 20 years.

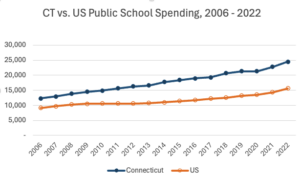

Despite Connecticut’s spending increase of $1,684, or 7.4%, over 2021 — falling below the national average — the gap between national and state expenditures continues to widen. In 2006, the state’s per pupil spending was $12,323, which was $3,184 more than the national average. By 2022, this gap had grown substantially, with Connecticut spending $8,820 more per student than the national average.

Even with a lower-than-average percentage increase, Connecticut’s spending remains significantly higher than that of neighboring New England states that also have a high cost of living and powerful teacher unions. On a per pupil basis, Connecticut’s school spending is 11.6% more than Massachusetts and 22.5% more than Rhode Island.

Census data also reveals that Connecticut’s spending frenzy is largely fueled by instructional salaries and benefits, totaling $14,754 per pupil, which is 58% above the national average of $9,348. In the realm of support services or expenditures outside of the classroom, Connecticut spent $8,870 per pupil, outspending all other states, including New York, except for the District of Columbia ($12,879), Vermont ($9,682) and New Jersey ($9,347).

As Connecticut remains one of the top states for per pupil spending, public school student enrollment in the state has been shrinking since 2006, when it was 578,527. By 2023, this number had fallen to 512,652. An exception occurred in 2021 when the public school system gained 536 students, but enrollment dropped again the following year, losing 102 students.

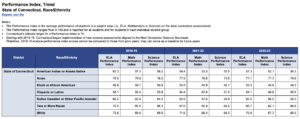

Notwithstanding rising spending, student achievement outcomes are mirroring the decline in enrollment. According to the state’s Performance Index, which measures the average performance of students in Math, English Language Arts (ELA), and Science, students have yet to recover academically to pre-pandemic levels. The index ranges from 0 to 100, with a state target of 75.

In the 2018-2019 school year, the state averages for all students, regardless of race, were 67.7 in ELA, 63.1 in Math, and 63.8 in Science. By the 2022-2023 school year, these averages had dropped to 63.9 (ELA), 59.7 (Math), and 61.6 (Science).

The data is even more concerning for students of color. Black and Latino students, who were already underperforming before the pandemic, have continued to see their scores decline. Essentially the state’s public school system continues to do less with more (see chart below).

The data hasn’t deterred the teachers’ unions from demanding more cash while resisting any alternatives to traditional public schooling, even though such alternatives would not impact their financial resources.

This past legislative session, the Connecticut Education Association (CEA) — the state’s largest teachers union — was demanding a state minimum teacher starting salary and guaranteed step increases to be a right in contract negotiations. They also wanted hero pay to “acknowledge teachers’ role in providing quality education during the pandemic.” Ultimately, these measures failed.

Simultaneously, the CEA, along with the Connecticut American Federation of Teachers (AFT), played a crucial role in defeating a bill that would have offered tax credits for donations to nonprofit organizations providing scholarships to low-income families for private school attendance.

The teachers’ unions won’t hesitate to resort to threats against lawmakers to get their demands met. During the 2023 legislative session, a publicized email from the two unions warned that any vote in favor of a bill aimed at changing the charter school approval process would result in a failing grade on the CEA’s “legislative report card” — an annual evaluation grading each legislator based on their voting record on specific bills.

Lawmakers who fail to align with the unions’ objectives risk losing their support during election season, which includes not only financial backing but also crucial campaign efforts such as organizing get-out-the-vote drives and door-to-door canvassing to secure the victory of their favored candidates.

The demand for more funds from teachers’ unions is also happening at the local level.

On May 24, the New Haven Federation of Teachers (NHFT) along with the Connecticut American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME Council 4) held a rally calling on the city to increase the public school budget by $12 million.

NHFT President Leslie Blatteau complained that the mayor’s proposed 2024-25 budget allocates “only” 31 percent to the Board of Education. “We say enough is enough. We say fund our schools,” she demanded. “We want the alders to send us and our students a message that they believe in us.”

It’s worth noting that a recent report by the CEA affiliate National Education Association (NEA) highlights that the average teacher salary in Connecticut is $83,400, ranking as the 6th highest in the nation.

Additionally, the average starting salary for teachers in Connecticut is $48,784, placing it 13th highest in the country. For comparison, the report indicates that the national average teacher salary is $69,544, and the starting salary is $44,530.

Connecticut’s education system is a striking example demonstrating that more spending doesn’t guarantee better results. While the state continues to pour funds into its schools, student performance, particularly among marginalized communities, continues to falter.

The persistent demands for increased spending by teachers’ unions, without corresponding improvements in student achievement, suggest that financial resources alone cannot resolve the deeper issues plaguing the education system. Instead of focusing solely on funding, Connecticut needs a comprehensive reform strategy that prioritizes accountability, innovation and genuine educational equity. Only then can the state hope to see real progress in its public schools.

This Week on Yankee’s Podcast Y CT Matters

The Washington Free Beacon reported that up to half of UCLA’s medical students are failing basic tests of medical competence — and outlawed affirmative action practices are to blame. Andrew Quinio, an Equality & Opportunity Attorney at the Pacific Legal Foundation, provides insights into the legality of affirmative action in California, and how using race instead of merit negatively impacts everyone, including those who need the most help. Read the full report here.

Click here to listen