The Allied and Central Powers had been fighting in the “war to end all wars” for nearly three years when the United States officially entered the conflict on April 6, 1917.

Prior to the declaration, American public opinion and government policy weighed heavily toward neutrality and isolationism; yet even an ocean between the European and North American continents could not quell threats of espionage, as hundreds of civilians died in the sinking of U.S. merchant and passenger ships — as well as the R.M.S. Lusitania in 1915 — by German submarines.

America mobilized an expeditionary force that eventually totaled more than 4 million men by the war’s end, Nov. 11, 1918. Of those, 67,000 hailed from Connecticut, providing manpower to the 26th Division, 76th Division, 102nd Infantry Regiment and the African American 372nd Infantry Regiment in the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). Many served with distinction, including Medal of Honor recipients and even a dog, while the state became a hub for war-time industrialization and recreational creature comforts for the ‘Doughboys’ stationed around the world.

With America’s involvement (its first defense of foreign soil) and Connecticut’s critical role, the Allies won the war and secured a peace until the rise of fascism and Nazism in the 1930s. This is the story of Connecticut in the First World War.

‘The Yanks Are Coming’

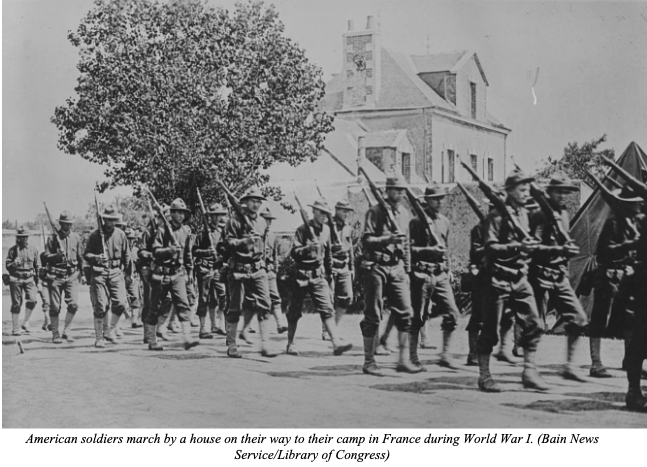

In the summer of 1917, almost 4,000 enlisted men from across Connecticut in the 1st and 2nd Regiments trained at Camp Yale on the grounds near the present-day Yale Bowl. However, the individually undermanned regiments were consolidated into the 102nd Infantry Regiment, which was then folded into the newly formed 26th Division (nicknamed the “Yankee Division” for consisting entirely of New Englanders).

The jovial times at Camp Yale ended when the “Yankee Division” shipped to France in fall 1917, the first National Guard unit to do so. There, the Connecticut doughboys spent a winter near the town of Neufchateau in the Vosges’ foothills in what Capt. Daniel Strickland — a veteran of the war — labeled as the “Valley Forge of France” in his book Connecticut Fights: The Story of the 102nd Regiment. He compared a soldier’s life to “almost like that of a galley slave” and that “there was none too much food at times, shoes wore out, and makeshifts were the order of the day for clothing.” Throughout the “weary, cold winter,” the men’s flagging spirits yearned to fight, and “dissatisfaction broke out not only among the men, but especially among the officers.” The “grumbling,” as Strickland describes, was also in reaction to the “ever present damnable mud” that caused trench foot for numerous soldiers.

The jovial times at Camp Yale ended when the “Yankee Division” shipped to France in fall 1917, the first National Guard unit to do so. There, the Connecticut doughboys spent a winter near the town of Neufchateau in the Vosges’ foothills in what Capt. Daniel Strickland — a veteran of the war — labeled as the “Valley Forge of France” in his book Connecticut Fights: The Story of the 102nd Regiment. He compared a soldier’s life to “almost like that of a galley slave” and that “there was none too much food at times, shoes wore out, and makeshifts were the order of the day for clothing.” Throughout the “weary, cold winter,” the men’s flagging spirits yearned to fight, and “dissatisfaction broke out not only among the men, but especially among the officers.” The “grumbling,” as Strickland describes, was also in reaction to the “ever present damnable mud” that caused trench foot for numerous soldiers.

After the harsh winter, the barrage of fighting came. While the 26th Division and the 102nd Regiment held their first defensive and offensive operations in the Chemin des Dames (a sector on the Western Front) in March 1918, its first major engagement — and the first undertaken by American troops — came at the town of Seicheprey on April 20. In the early morning, “all hell was let loose” by the Germans as a “constant deluge of shells” and “deadly rain of high explosive and gas” pounded the Allied lines, recounts Strickland. Some historians speculate the Germans wanted not only to taunt, but to test the inexperienced Americans’ resolve. Eventually, more than 3,000 Germans raided and captured the town — albeit briefly. Despite the initial setback, the Connecticut doughboys displayed immense fortitude against the battle-hardened Huns, leading a counterattack that successfully recaptured the Allied trenches.

More than 80 from the 102nd were killed in the effort.

Seicheprey was only a precursor to the 26th and 102nd’s adaptability on the battlefield, and its “knack for tactical innovation,” according to the Connecticut National Guard’s website. For the rest of the year until the Nov. 11 Armistice, the Connecticut men fought in every major battle in which Americans participated including Aisne-Marne, Chateau-Thierry, St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive — the final Allied offensive, the largest operation of the AEF and the deadliest campaign in American history. By the war’s end, the “Yankee Division” was in combat longer than any American division, suffering the greatest number of gas casualties in the AEF.

The other divisions — the 76th and African American 372nd Infantry Regiment — served valiantly but their accomplishments are, sadly, not as well documented (at least with online resources). Known as the “Liberty Bell Division,” the former’s distinction is that it was the first division of the National Army to be drawn from civilian ranks through the draft. Some hints suggest the 76th largely served to replace other front-line units; the 372nd, meanwhile, was an entirely segregated regiment, drawing soldiers from across the country, and members received numerous decorations while serving under French Command in Champagne and the Vosges, according to the American Battle Monuments Commission.

But, as in other wars, there were those who went beyond the call of duty. Here are a few Connecticut residents who distinguished themselves in battle:

Ralph Talbot

Born on Jan. 6, 1897, the former South Weymouth, Mass., native enrolled at Yale University in the late 1910s. In June 1917, after the United States entered the war, Talbot joined the DuPont Aviation School in Wilmington, Del., and trained at various bases in Massachusetts and Florida, before being commissioned as a second lieutenant in May 1918. By mid-July, he was overseas with the 1st Marine Aviation Force. Talbot displayed “exceptionally meritorious service and extraordinary heroism” in a number of air raids into enemy territory. On Oct. 8, he was “attacked by nine enemy scouts, and in the fight that followed shot down an enemy plane.” A few days later, on Oct. 14, Talbot broke from formation “on account of motor trouble” — and it was not much later that 12 enemy scouts attacked him. In the ensuing dogfight, he outmaneuvered the scouts to give his wounded observer time to “clear” a jammed gun, and shot down one plane. As his Medal of Honor citation reads, “With his observer unconscious and his motor failing, he dived to escape the balance of the enemy and crossed the German trenches at an altitude of 50 feet, landing at the nearest hospital to leave his observer, and then returning to his aerodrome.” However, Talbot would not see the war’s end; he died nearly two weeks before the Armistice on Oct. 25, 1918, when his engine immediately failed during a test flight’s takeoff. He posthumously received the Medal of Honor on Nov. 11, 1920.

John MacKenzie

MacKenzie was born in Bridgeport on July 7, 1886. At 16 years old, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy, serving until 1907, attaining the rank of Coxswain. After the United States’ entry in World War I, MacKenzie reenlisted where he was assigned to the U.S.S. Remlik. On Dec. 17, 1917, the Remlik was patrolling the French coast when it “encountered a heavy gale.” During the storm, a depth charge (an explosive device) fell on deck, which threatened to seriously damage the ship. With disregard for his own life, MacKenzie sat on the depth charge “as it was impracticable to carry it to safety,” but nevertheless “prevented a serious accident to the ship and probable loss of the ship and the entire crew.” For his actions, MacKenzie received the Medal of Honor, reportedly the first Naval reservist to do so. MacKenzie survived the war, entering the restaurant business. On Dec. 26, 1933, he died after a heart attack. A ballfield in Holyoke, Mass., is named in his honor.

Raoul Lufbery

Lufbery only spent two years in Connecticut, working at a silver-plating factory in Wallingford, yet the former French native was “probably the state’s greatest hero of the First World War,” according to ConnecticutHistory.org. After living a nomadic life, Lufbery joined the French Foreign Legion as a U.S. citizen in August 1914, and then enlisted in aviation school where he “trained on two-seaters and flew missions with a bomber squadron before transferring to combat fighter school in April 1916.” The next month, Lufbery joined what would become known as the Lafayette Escadrille — a squadron of American volunteer combat pilots that developed a “reputation for devil-may-care derring-do,” according to author David Drury. Lufbery was a standout, becoming the “first recognized American air ace after downing his fifth enemy aircraft.” Throughout the war, the ace downed at least 17 enemy planes and trained U.S. pilots after America officially entered the conflict. He died in a dogfight near Toul, France, on May 19, 1918.

Sgt. Stubby

One of the more famous Connecticut heroes of the American war effort did not even walk upright, but on all fours — because he was a bull terrier. Stubby wandered into the military encampment at the Yale Bowl where the 102nd Infantry trained, and quickly became the unit’s mascot. The dog was smuggled overseas and, as his biography states, “sailed into doggy legend.” He served valiantly, providing morale-boosting support, as well as the “occasional early warning about gas attacks or by waking a sleeping sentry to alert him to a German attack.” In his New York Times obituary, he would “keep a wounded soldier company” and “if the suffering doughboy fell asleep, Stubby stayed awake to watch.” Stubby took part in four major offensives, and even captured a German spy and “saved a doughboy from a gas attack,” according to his obituary. In the former instance, Stubby seized his prisoner by the breeches until members of his unit arrived. He also sustained several combat injuries and gas attacks throughout his military service. Nevertheless, Stubby survived World War I — and became a celebrity in the process, meeting three U.S. presidents and participating in American Legion parades. He died in 1926, and his body is on display at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

A Hub for Industrialization, Charity

As Connecticut ramped up “preparedness” before entering the fray under then-Gov. Marcus Holcomb’s leadership, Prof. L.P. Breckenridge — from Yale University’s Sheffield Scientific School — authored a Yale Daily News article published on Feb. 1, 1917, in which he recognized that “the war of to-day [sic] is not only a war between men on the firing line but a supreme test of industrial capacity and economy at home, of science and the application of science to the everyday routine.”

Connecticut not only passed the proverbial test, but excelled, becoming an “essential industrial center” throughout America’s involvement in the war, according to the Elihu Burritt Library’s exhibit “Industry in Connecticut during World War I.” Developed in cities like Waterbury, Hartford and Bridgeport in the mid-1800s, the state’s industries were primed for contributing to the war effort. According to David Drury, author of Hartford in World War I:

Connecticut was ahead of the game when it came to war preparation and began a war census before the United States declared war on Germany. As European governments looked for companies to produce war materials, the state had already begun creating lists of potential war producers.

The state’s myriad of industries stepped up, making Connecticut an arsenal for the Allied forces.

Companies like Scovill, Chase Brass and Copper Company, and American Brass — who all called the “Brass City” home — produced shells, fuses and other brass war products for the Allies. Meanwhile, the rubber industry in Naugatuck spearheaded by the giant United States Rubber Company (a consolidation of nine companies, including one founded by Charles Goodyear) manufactured boots and tires even before America’s entry into the war, receiving $1.5 million in contracts from the British and French governments in December 1914.

Similarly, several of the largest gun manufacturers in the nation at the time — Winchester Repeating Arms Company, Remington Arms and Colt — also called Connecticut home and produced hundreds of thousands of rifles, pistols, machine guns and arms cartridges. Other companies also transitioned quickly to war production, such as Pratt & Whitney whose “3,400 employees were devoted completely to war manufacturing,” according to the Elihu Burritt Library’s exhibit; additionally, the New Britain houseware company Landers, Frary & Clark transitioned from making cutlery to fashioning calvary swords, trench knives, bayonets, as well as gas mask parts, mess kits, canteens and canteen cups.

Throughout the war, Connecticut’s industries produced more than 50 percent of all ammunition for the United States, and proved vital in the Allies’ fight against the Central Powers even before America’s formal declaration.

Yet the Homefront consisted not only of manufacturing munitions and materials for combat, but also of fundraising initiatives undertaken by the Red Cross, and the state’s municipalities that sold Liberty Loans (war bonds) — including New Britain, which raised $2.4 million (or more than $46.5 million in 2022, according to the American Institute for Economic Research’s calculator).

One Connecticut charitable institution notably rose to the occasion. Gen. John Pershing — commander of the AEF — stated, “of all the organizations that took part in the winning of the war, with the exception of the military itself, there was none so efficiently and ably administered as the Knights of Columbus.”

Founded by Blessed Michael McGivney in 1882, the New Haven-based Knights of Columbus (K of C) had initially been an insurance, fraternal organization primarily assisting Irish Catholic families. By the turn of the 20th century, the fledgling Order expanded its operations, providing charity to communities across the country.

This mission was enhanced when the Great War arrived. On April 14, 1917, the K of C Board of Directors assured President Woodrow Wilson of the organization’s “patriotic devotion of 400,000 members,” and soon thereafter established a Committee on War Activities. Through the committee, the K of C coordinated “fundraisers and war relief efforts” that eventually raised $14 million (or more than $300 million today).

Yet the K of C became well-known for the nearly 150 recreation ‘huts’ scattered across U.S. military bases in the United States and Europe that offered “an escape from the war,” according to “K of C Service in the Great War” by Joseph Pronechen. Their slogan “Everybody Welcome, Everything Free” was true as advertised — no one was turned away based on religion, rank or even race, and military personnel did not pay for any of the creature comforts offered by the K of C secretaries (nicknamed ‘Caseys’) who operated the facilities. As noted in Pronechen’s article:

In the huts, soldiers had the opportunity to attend Mass, go to confession, hear a music recital, see vaudeville entertainment or watch a movie. They could attend a dance, sit ringside at popular boxing competitions, write letters home (the Knights provided 1,800 tons of stationery), or read a book from the library. …The Caseys dispensed items such as candy, gum, cigarettes, playing cards, sewing kits, razors, postcards and rosaries. The KC secretaries sometimes even went to the front lines and trenches to hand out items to soldiers. They also operated large mobile food trucks known as rolling kitchens — a Knights’ invention — to bring the men hot coffee, cocoa and other warm food.

Some of the most famous Caseys were major league ballplayers like Hall of Famer Johnny Evers — the former Chicago Cubs second baseman part of the famous double-play triplet, Tinker to Evers to Chance. Aside from teaching French locals baseball and organizing games for the soldiers, Evers journeyed to the frontlines, distributing “welcome cigarettes” to troops “during all the time he was so engaged” and avoiding German gunfire, according to the Order’s magazine Columbiad in 1919. Baseball was so often requested by the Doughboys that the K of C provided enough equipment that nearly five thousand games were played daily with “outfits supplied them by the Knights.”

Even after the war, the huts remained open, including one in Koblenz, Germany, that produced more than 40,000 doughnuts daily for AEF troops. The K of C also coordinated the first military pilgrimage to Lourdes, France — the site of a 19th century Marian apparition — for nearly 3,000 soldiers still stationed in Europe in March 1919.

The K of C’s massive undertaking would be assumed by the United Services Organization (U.S.O.) in World War II; nevertheless, the organization was — and remains — dedicated to ensuring the “spiritual and temporal well-being of military personnel.”

The War to End All Wars

While estimates vary, a 2011 report by the Robert Schuman European Centre calculated that more than 16.5 million people died from combat, starvation, genocide and disease in World War I; nearly 1,100 were from Connecticut, many of whom died from influenza.

Due to the sheer volume of death and destruction unlike anything experienced before in human history, the First World War’s casualties are often referred to as the “Lost Generation.” Meanwhile, the Treaty of Versailles — signed on June 28, 1919 — did not sow a lasting peace between the Allies and Germany, but rather resentment among the latter’s populace that eventually gave rise to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. Ultimately, World War I was an ugly and disillusioning struggle; thankfully, peacemakers after World War II heeded many of its lessons and laws of warfare subsequently prohibited many of its most inhumane features, including chemical weapons.

Regardless, one thing is for certain: Connecticut was instrumental on the battlefield and the Homefront. It is safe to say that without the Constitution State, the men fighting “over there” would not have been as well-equipped spiritually or physically to fight and defeat the Central Powers.

Yet, like in the days preceding the First World War, today’s world appears to be ‘sleepwalking’ into what could be another full-scale world conflict. In these times of uncertainty, perhaps it is best for U.S. leaders to adopt a “preparedness” policy and heed the words of America’s great founding father and first president, George Washington, from his Fifth Annual Address to Congress:

“There is a rank due to the United States among nations which will be withheld, if not absolutely lost, by the reputation of weakness. If we desire to avoid insult, we must be able to repel it; if we desire to secure peace — one of the most powerful instruments of our prosperity — it must be known that we are, at all times, ready for war.”

On the Armistice’s 105th anniversary, may we remember the fallen for their sacrifice; may we remember the true cost of war; and may we pray to keep another generation from the throes of desolation.

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler

What neat history do you have in your town? Send it to yours truly and I may end up highlighting it in a future edition of ‘Hidden in the Oak.’ Please encourage others to follow and subscribe to our newsletters and podcast, ‘Y CT Matters.’