On December 23, the New Haven Federation of Teachers (NHFT) announced on social media that its bargaining team had met privately with members of New Haven’s delegation to the General Assembly. The meeting, according to the union, focused on “what teachers need,” “what kids need,” and the union’s vision for the city’s schools.

The Facebook post read less like a routine update and more like a declaration of alignment. NHFT wrote that lawmakers did not merely listen, but agreed with the union’s position and “committed to the work ahead” to make those demands a reality. The message did not clarify whether those commitments were political, legislative, or rhetorical — or how they would interact with the city’s ongoing contract negotiations.

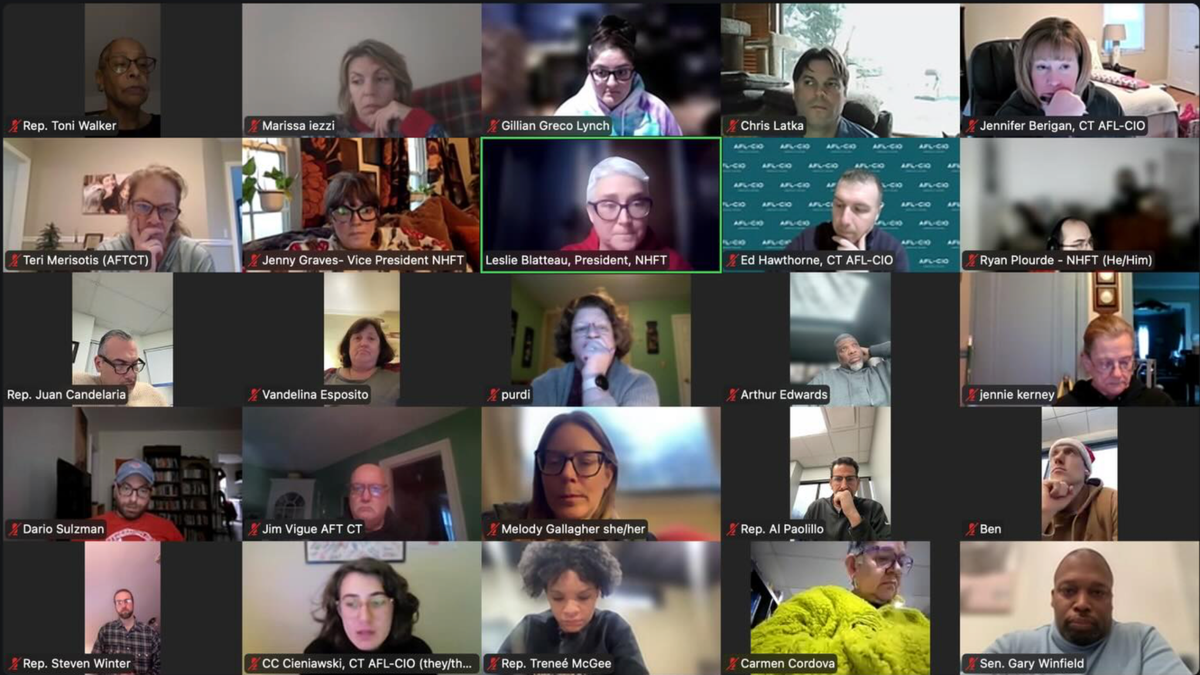

The legislators on the call were not peripheral figures. Participants included Representatives Toni Walker, Juan Candelaria, Steven Winter, Treneé McGee, Al Paolillo, and Senator Gary Winfield — all members of the New Haven delegation who routinely vote on policies that affect municipal budgets. These are the same lawmakers who approve state mandates that increase local costs and then return home to communities already struggling to absorb them.

What the post did not address is where negotiations now stand — or who ultimately pays when state-level wishes collide with municipal reality. Just days earlier, contract talks between the city and the teachers’ union had broken down, sending the dispute toward binding arbitration.

Health care costs have emerged as the central issue. Union leaders argue that rising premiums have offset recent wage gains and are placing pressure on teachers. City officials counter that the union’s proposed shift into the state’s Partnership Plan 2.0 — a state-run health-insurance option allowing non-state public employees to buy into the state employee health plan — would destabilize New Haven’s existing insurance pool, increase premiums for other municipal workers, and significantly raise long-term costs for local taxpayers.

With no agreement reached, state law now places the final decision in the hands of arbitrators.

That context matters. Arbitration does not occur in isolation. It produces binding outcomes that lock in costs — not just for the current year, but for years to come.

Against that backdrop, the decision by state lawmakers to meet with the union and publicly signal agreement raises important questions about roles and responsibility. This was not a neutral listening session. It occurred as negotiations collapsed, arbitration loomed, and city officials warned that the union’s proposals would drive up costs across the entire municipal workforce.

As state legislators, members of the New Haven delegation routinely support policies that limit municipal flexibility. They have backed expansions of special-education obligations without fully reimbursing districts, election laws that permanently increase staffing and compliance costs, public-safety mandates that add training requirements and liability exposure, and redevelopment policies that attach prevailing-wage and other statutory conditions to state aid.

The Connecticut Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (ACIR) has long classified these actions as mandates requiring municipalities to spend local revenue, noting that while many appear manageable on their own, their cumulative effect steadily tightens local budgets. Cities like New Haven, with large school systems and high service demands, bear those costs disproportionately.

That is the fiscal landscape in which the current labor dispute is unfolding. It is a landscape shaped in no small part by the very lawmakers now signaling support for one side of the negotiation.

Collective bargaining is local by design because local officials are accountable for the tradeoffs it requires. They must balance contracts against taxes, services, and long-term fiscal stability. When state legislators insert themselves into that process, particularly at the moment arbitration is triggered, they exert influence without bearing responsibility for the outcome.

These consequences are immediate, with taxpayers left to absorb the cost. Arbitration awards don’t come with new revenue. If arbitrators approve higher pay or richer benefits without offsetting funds, the cost falls squarely on New Haven taxpayers. Property taxes rise, services are reduced, or both.

Larger class sizes, shorter library hours, delayed road maintenance, and fewer public-safety resources are not rhetorical warnings; they are the real budget pressures cities face when fixed costs increase and flexibility disappears.

City officials have been clear that the proposals now headed to arbitration would strain New Haven’s already tight budget. That reality is precisely why negotiations broke down in the first place.

Yet at the moment the contract moved toward binding arbitration — members of the General Assembly chose to publicly align themselves with the union’s demands. That alignment does not resolve the fiscal problem. It simply shifts the burden.

In the end, arbitration will settle the contract. Taxpayers will settle the bill. And the same lawmakers applauding “solutions” today will not be the ones explaining the next tax increase or service cut when the numbers no longer add up.