Heroes are remembered. Their bravery, perseverance, sacrifice and leadership during times that try men’s souls for the cause of freedom exemplify the human spirit’s awe-inspiring capacity to endure.

The American Revolution called for such endurance, producing many heroes: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, the Marquis de Lafayette, John Adams, Nathaniel Greene and Nathan Hale, to name a few. Arguably, no other era in U.S. history has had such a confluence of ‘mighty men’ — to borrow a Biblical term — wrestling intellectually and philosophically to establish a new government, all while fighting against one of world history’s most dominating empires, Great Britain.

Rightly so, a grateful nation has subsequently honored them in memorials, monuments, municipalities, schools, street names, memorabilia and more. (Even as action figures, which yours truly received as a kid.)

But what about the common man?

Though “first in war” (as eulogized by Henry Lee, a major general in the Continental Army), Washington did not battle the British Army alone. To be a leader, one needs followers — and those soldiers, whose names and experiences are lost to the American consciousness, also risked life and liberty much like the era’s giants. Indeed, they too, fought not only for pay like mere mercenaries, but also for independence.

Personal narratives from that time were seldom recorded. However, one of the more extensive insights into a Continental Army soldier’s life was published by 70-year-old Joseph Plumb Martin, who joined the Connecticut militia at 15, in A Narrative of Some of the Adventures, Dangers and Sufferings of a Revolutionary Soldier (1830). As George Scheer, editor of Yankee Doodle Boy: A Young Soldier’s Adventures in the American Revolution (1995) that reprinted Martin’s recollections, states, “[Martin] knew what his war was all about — freedom,” adding, “He was a youth who sensed the simple truth that a decent cause must and shall prevail, so long as men of belief stand for it without compromise and without fear.”

Martin’s duty spanned seminal events in the war, from New York to Valley Forge to Monmouth to Yorktown, for seven hard years filled with starvation, bitter cold and mutiny as well as harrowing British cannonballs and gunfire. It was hardly an idealistic affair. But the tale nearly went unnoticed, receiving little regard during his lifetime, until the mid-20th century when it was republished as Private Yankee Doodle (1962). Today, his first-hand experience is “considered a classic as well as a useful tool for historians in understanding the life of the common soldier in the Continental Army,” according to American Battlefield Trust.

This is story of Joseph Plumb Martin, otherwise known as the “Voice of the Common American Soldier.”

The Toils of an Army

Martin made his “appearance in this crooked, fretful world,” as he describes, on Nov. 21, 1760, in Berkshire County, Ma. His father, a Windham native, was a Congregational minister and Yale alum (1755), who married an affluent “farmer’s daughter” from the New Haven area.

At seven years old, Martin’s parents sent him to stay with his maternal grandparents in Milford, Conn. From his narrative, his childhood was pleasant, and his grandfather (or “grandsire”) was “indulgent to me almost to a fault” — as well as politically invested. His grandfather often discussed the “disturbances” caused by British tax polices like the Stamp Act, “while working in the fields, perhaps as much to beguile his own time as to gratify my curiosity.” Even so, Martin believed if war came between the colonies and mother country, he would not “get caught in the toils of an army” for he lived comfortably. In retrospect, he considered himself a “real coward” in the antebellum years.

Yet on April 21, 1775, Martin heard bells and guns fire while plowing the fields. After arriving in town to see the commotion, he learned that two days earlier, Massachusetts minutemen and British soldiers had fired the “shot heard round the world” in Lexington and Concord, the opening salvo of the American Revolutionary War. Men enlisted and Martin, attracted to payment (a dollar), discarded his initial reluctance and felt the “seeds of courage” sprouting. However, Martin was too young to become a soldier.

Between then and June 1776, the young teen “felt more anxious than ever, if possible, to be called a defender of my country.” As American Battlefield Trust explains, Martin “threatened to run away and join up with American maritime privateers,” whom his grandparents detested. After receiving “tacit consent” to serve with the Connecticut militia, he eagerly enlisted for six months. Nevertheless, his grandparents confronted him, but then fitted him with “arms, accoutrements, clothing, and cake, and cheese in plenty, not forgetting to put my pocket Bible into my knapsack.” Martin often writes of their kindness, even in that moment, and his regret of hurting and leaving them, but he “was now, what I had long wished to be, a soldier; I had obtained my heart’s desire.”

The 15-year-old, however, could not have known he was pledging nearly a decade of his life to the Revolutionary cause.

He set off for New York, where the Continental Army took defensive positions against an impending British siege. While on duty, Martin participated in “recreation,” a euphemism for purloining. Though he “never wished to do any one an injury,” the young teen and his compatriots did steal some Madeira wine from a local shop, which he later tossed from his quarters to avoid a reprimand. By late August, however, the offensive began, and Continental Army suffered a string of devastating defeats in the battles of Brooklyn (or Long Island), Kip’s Bay and White Plains.

It was during this span Martin had his first of many brushes with death. During a lull in the Battle of Kip’s Bay, he was in an old warehouse perusing papers strewn over the floor when “there came such a peal of thunder from the British shipping that I thought my head would go with the sound.” He made a “frog’s leap for a ditch, and lay as still as I possibly could, and began to consider which part of my carcass was to go first.”

The American retreats were scattered scenes of mass confusion as the British cut off various escape routes. At one point, in the mayhem, Martin hid in a bog and the “British came so near to me that I could see the buttons on their clothes”; all the while, he brought to safety a “sick companion,” who wished to die, eventually finding other members of his regiment.

The New York campaign was nearly a complete disaster for Gen. Washington and the army. In truth, had Gen. Charles Cornwallis not “prohibited the Hessians from destroying American forces led by Washington crossing the Hackensack River,” as Mount Vernon asserts, the Revolution could have been over then. For Martin, he was sent with “our sick” to Norwalk, Conn., as a nurse. In that time, he fraternized to some extent with the locals who were “almost entirely” Tories, those loyal to the British during the war. He often procured milk from an older woman who would “give me a lecture on my opposition to our good king [sic] George.” Eventually, he rejoined the regiment “undergoing hunger, cold and fatigue” until he was discharged on Christmas Day, 1776.

When his six months ended, Martin initially refused to re-enlist, returning to Milford. However, after much persuasion from a friend and “elbow relation” (a lieutenant cousin-in-law), as well as boredom, he resolved to be soldier once more.

He joined the 8th Connecticut Regiment (or the 17th Continental Regiment) in Newtown; en route to New York, he witnessed the devastation the British inflicted on Danbury residents, writing:

“The town had been laid in ashes, a number of the inhabitants murdered and cast into their burning houses, because they presumed to defend their persons and property, or to be avenged on a cruel, vindictive invading enemy. I saw the inhabitants, after the fire was out, endeavouring [sic] to find the burnt bones of their relatives amongst the rubbish of their demolished houses.”

In the following months, Martin was inoculated with smallpox; an accident resulted in an injury to his ankle, which never fully recovered throughout his life. Nevertheless, he continued to march with his outfit to Pennsylvania, as Gen. William Howe and the British occupied Philadelphia after the Battle of Brandywine Creek (Sept. 11, 1777). Yet, in order to move warships into the city, the British had to capture several positions, including Fort Mifflin — a defensive outpost on Mud Island in the Delaware River. Martin was sent to the “besieged” fort. From Sept. 26 to Nov. 16, the young teen and other Connecticut soldiers “endured hardships sufficient to kill half a dozen horses” as the British pounded Fort Mifflin with a barrage of cannon fire. He was “without provisions, without clothing, not a scrap of either shoes or stockings to my feet or legs, and in this condition to endure a siege in such a place as that, was appaling [sic] in the highest degree.”

The men were sleep deprived, fatigued, “cut up like cornstalks” and had limited arms to return fire. In one anecdote, Martin describes how officers offered rum to those who recovered British cannonballs, which would be “conveyed off to our gun to be sent back again to its former owner.” During the siege, Martin even believed Divine Providence protected him on several occasions, particularly after a sergeant was killed performing a task he nearly volunteered for.

The fort’s destruction was devastating; yet because Martin and other Continental Army soldiers held out for so long, it delayed the British advance long enough to “prevent attacking General George Washington’s worn-out army before the opposing forces settled into winter quarters,” according to the U.S. Naval Institute. Miraculously, Martin escaped capture himself, as his regiment — or what was left of it — moved to the Jersey shore one November evening under the cover of darkness. Although he survived, Martin discovered his friend was killed, finding him in a “long line of dead men who had been brought out of the fort.”

‘Defence’ of Our Injured Country

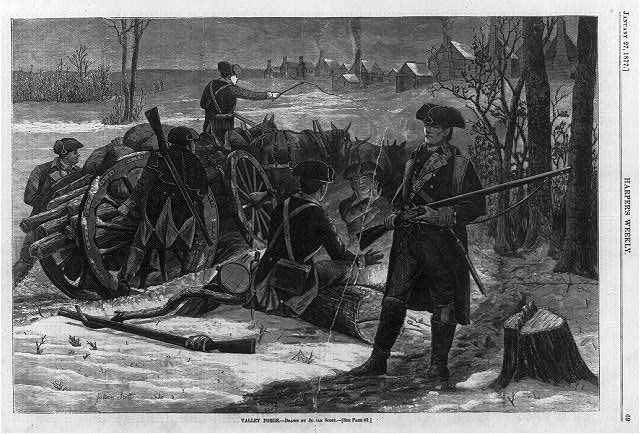

By the time the Connecticut regiment arrived at Valley Forge on Dec. 18, 1777, for the winter, Martin was “disheartened” as the men were in a constant “weak, starved and naked condition.” Nevertheless, the young teen — who only turned 17 the month before — did not think to abandon the cause even though “we were now absolutely in danger of perishing.” As he attests:

“…we had engaged in the defence [sic] of our injured country and were willing, nay, we were determined to persevere as long as such hardships were not altogether intolerable. …But a kind and holy Providence took more notice and better care of us than did the country in whose service we were wearing away our lives by piecemeal.”

While at Valley Forge, Martin was assigned to conduct foraging expeditions. In this assignment, he fared better than the 12,000 others encamped throughout the winter and early spring. Indeed, more than 2,000 died from disease. He shares:

“Our duty was hard, but generally not altogether unpleasant; —I had to travel far and near, in cold and in storms, by day and by night, and at all times to run the risk of abuse, if not of injury, from the inhabitants when plundering them of their property, (for I could not, while in the very act of taking their cattle, hay, corn and grain from them against their wills, consider it a whit better than plundering, —sheer privateering.) …I doubt whether the people of New England would have borne it as patiently, their ‘steady habits’ to the contrary notwithstanding.”

Today, Valley Forge is known in the American story as the “birthplace of the American army,” according to History.com, since the “weary troops emerged with a rejuvenated spirit and confidence as a well-trained fighting force,” with much credit going to Prussian officer Friedrich Wilhelm Baron von Steuben. But the army needed sustenance, and Martin’s work was crucial to its survival.

As the weather warmed, hostilities were raised again, and the Continental Army — along with Martin’s regiment — pursued the British after the latter was ordered to evacuate Philadelphia for New York. On June 28, 1778, the two opposing sides clashed on a hot, humid day outside Monmouth Court House, New Jersey. As the battle raged, the Continental Army’s prospects looked grim as Gen. Charles Lee blundered an attack against the British, which led to a retreat. Gen. Washington “prided himself on his ability to control his temper,” Mount Vernon states — but not that day. Martin witnessed the Commander-in-Chief’s rage and the efforts to galvanize his men to continue fighting, riding out into battle “while the shot from the British Artillery were rending up the earth all around him,” he notes.

Martin did fight on and may have even killed a soldier, writing, “I hope I did not kill him, although I intended to at the time.” In the end, the Battle of Monmouth’s outcome was inconclusive since both sides had a similar number of casualties; additionally, the British were able to escape in the dead of night bound for their original destination. Still, the battle exhibited the Americans’ training and resilience, and Washington’s heroics solidified him as indispensable to the Revolutionary War’s cause. (After all, he had other political adversaries vying for his position at the time.)

For the rest of 1778, Martin’s regiment moved north into various spots in New York and Connecticut; while in White Plains, he was transferred to the Light Infantry, which was “always on the lines near the enemy, and consequently always on the alert, constantly on the watch,” as he describes. During these months, Martin nearly lost his life while trying to find a water source at night. A British patrol of more than 10 men “had a hack” on him, firing with bullets “pass[ing] so near my head as to cause my ear to ring for some time after.” He eventually managed his way back to his camp and safety, but not before suffering a knee injury after running into a stump.

The winter was hard, and with little food, the grievances between the men and their officers nearly ignited; but, after receiving more supplies, Martin and company “endeavoured [sic] to bear it with our usual fortitude, until it again became intolerable, and the soldiers determined to try once more to raise some provisions, if not, at least to raise another dust.” In time, another more significant “dust” would occur. However, in February 1779, Martin obtained a furlough, staying with his grandparents for a few weeks before being sent to New London, New Haven and back to the Hudson River Valley. In terms of combat, 1779 was a quiet year in which Martin saw no major action.

When the regiment encamped at Morristown, N.J., the “faithful companion” of hunger returned in full force. In a troubling episode, he testifies:

“We were absolutely, literally starved; — I do solemnly declare that I did not put a single morsel of victuals into my mouth for four days and as many nights, except a little black birch bark which I gnawed off a stick of wood, if that can be called victuals. I saw several of the men roast their old shoes and eat them, and I was afterwards informed by one of the officer’s waiters, that some of the officers killed and ate a favourite [sic] little dog that belonged to one of them. —If this was not ‘suffering’ I request to be informed what can pass under that name.”

At some point, Martin received a portion of “beef, but no bread” and rice “once in a while.” Even Washington took notice of the men’s hunger, writing they went “5 or Six days together without bread,” highlighting the scarcity of resources. In January 1780, the Commander-in-Chief “put a quota on every county in New Jersey to provide flour and meat,” which averted mass starvation to the point where “the army was well fed” in February and March, according to American Battlefield Trust.

While the rest of the army was encamped at Morristown, Connecticut troops — including Martin — were stationed at outposts, moving between Westfield and Springfield, N.J., according to the U.S. National Park Service. Outpost duty lacked more sufficient food, surviving primarily on cornmeal, and endured frequent raids by Loyalists. Martin and others were relieved in May, but when they returned to the main camp in Jockey Hollow, the only food available was “a little musty bread and a little beef about every other day, but this lasted only a short time and then we got nothing at all,” he describes.

The moment was dire. The frustration reached a boiling point. As Martin recalls:

“The men were now exasperated beyond endurance; they could not stand it any longer; they saw no other alternative but to starve to death, or break up the army, give all up and go home. This was a hard matter for the soldiers to think upon; they were truly patriotic; they loved their country; and they had already suffered every thing short of death in its cause. …Here was the army starved and naked, and there their country sitting still and expecting the army to do notable things while fainting from sheer starvation.”

On May 25, 1780, the soldiers mutinied, protesting the lack of food. In a scuffle, Col. Return Jonathan Meigs, wielding a sword, was bayoneted in the side. He survived the incident (his son was later governor of Ohio). However, the soldiers kept protesting despite passionate threats from officers. According to Martin, Pennsylvania troops were called to squash the mutiny, but once the soldiers realized the uproar’s cause, considered joining the protest. They were never used on the Connecticut mutineers. In the end, the “stir” as Martin writes “did us some good” for “we had provisions directly after, so we had no great cause for complaint for some time.” Only a few ringleaders were confined, according to the U.S. National Park Service.

As a 70-year-old man, Martin retrospectively still concludes the “army was not to be blamed,” arguing to his readers “suffer what we did and you will say so too.”

Rush On Boys

By 1781, Martin was a sergeant in the new Corps of Sappers and Miners. He, once again, obtained another furlough, but upon arriving in Milford, he found his sister was “keeping the house”: his grandmother had “gone to her long home” and his grandfather stayed with Martin’s uncle forty miles away. While home, Martin recruited others to join the fight.

When returning to West Point for duty, Martin discovered the “barracks entirely unoccupied, our men all gone, and not a soul could tell me where.” Eventually, he learned the army, led by Gen. Lafayette, marched to Virginia. By himself, Martin followed their trail down to Annapolis, Md., finding his corps there. He should have stayed at West Point, saving his energy, because the Sappers and Miners disembarked for the New York fort shortly after his arrival.

Back in New York, the Sappers and Miners were “constantly employed” with “making preparations” for the siege of the city, which had been occupied by the British since 1776. For Washington, recapturing New York was an aspiration, a chance to erase the mistakes from years before; thus, the Continental Army’s focus — more so than any other strategic goal — was on Manhattan. During the preparatory months (for a siege that never happened), Martin was on a reconnaissance mission, coming across nearly 40 enemy soldiers, who gave them chase. Shockingly, Martin’s shins were injured by a former “playmate” who deserted the Continental Army after “having been coaxed off by an old harridan, to whose daughter he had taken a fancy.” The enemy outfit never fired a shot; but Martin, miraculously, escaped. This episode was “the only time the enemy drew blood from me during the whole war,” he attests.

In another first, in the summer of 1781, Martin finally received a month’s pay since “the year ‘76 or that we ever did receive till the close of the war, or indeed, ever after, as wages” from French officers. Not long after, the Sappers and Miners were ordered to march toward Yorktown, Va., settling in “open view” of Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis and the British trapped between the Continental Army and the York River. He writes:

“We now began to make preparations for laying close siege to the enemy. We had holed him and nothing remained but to dig him out. Accordingly, after taking every precaution to prevent his escape, settled our guards, provided fascines and gabions, made platforms for the batteries, to be laid down when needed, brought on our battering pieces, ammunition, &c.; on the fifth of October we began to put our plans into execution.”

One night, while repairing trenches, Martin and his men were visited by Gen. Washington, though he did not recognize the Commander-in-Chief at the time. The anticipation was palpable. The wearying years were finally reaching their climax at Yorktown in October 1781; Martin felt a “secret pride swell my heart when I saw the ‘star spangled banner’ waving majestically in the very faces of our implacable adversaries” before the Continental Army discharged their guns at the British forces.

Before the main assault, in which Martin was tasked to capture Redoubt Number 10, he awaited the signal and watchword “Rochambeau” — in honor of the French Army’s commander, Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau — which “it sounded, when pronounced quick, like rush-on-boys.”

The men attacked when the signal was given. At first, Martin believed “the British were killing us off at a great rate,” but soon heard cries that the fort had been taken. The Sappers and Miners “cleared a passage for the infantry, who entered it rapidly.” Though some of Martin’s friends died in the assault, the Continental Army had been victorious, delivering a decisive blow against the British that led to the eventual end to hostilities, thus achieving independence.

Martin, now nearly 21 years old, witnessed the British surrender their arms with much satisfaction. After much suffering, nakedness, hunger, strife and death, he saw how the Continental Army was “able to persevere through an eight years war, and come off conquerors at last!”

Yet this is not where Martin’s story ends. In 1783, he was finally discharged after the war officially concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. He then moved to Maine, marrying Lucy Clewley in 1794. According to American Battlefield Trust, he unfortunately “became embroiled in a testy land dispute with former Continental Army Chief of Artillery Henry Knox,” which he lost. He managed to obtain a “little parcel of land that remained his and had five children.”

After the war, Martin lobbied the U.S. government for pension payments promised by Congress, arguing in his narrative that “I always fulfilled my engagements to [my country], however [my country] failed in fulfilling her’s with me.” By 1818, his pension was approved and “for the rest of his life he received $96 a year for payment of his service to the new nation,” as American Battlefield Trust notes.

He died on May 2, 1850, at 89 years old.

Martin could never have realized the deep, critical impact his personal narrative would have on the historical record and our understanding of life in the Continental Army. There is no propagandized glorification. Nor does he shirk the dark aspects of his service like the hunger, frustration, plundering, mutiny and death. He is even reserved by not repeatedly criticizing the British forces and Loyalists as brute, barbaric enemies. In short, Martin’s narrative is an honest account of what transpired — of what our forefathers endured.

His life is a reminder that America did not form out of thin air. It was won. Men and women toiled for years to achieve the independence and freedoms we, too often, take for granted. And while great men receive praise, the common soldier — or the “little men” as Martin writes — do not share in the same adulation from their countrymen. Yet these common soldiers, like Martin, secured our liberties. As his witness demonstrates, protecting these freedoms can be a grind, tough and may sometimes even seem hopeless. But perseverance is a quality to cherish and maintain, especially in this age of instant gratification and tendency toward despair.

In the end, not everyone can be like Washington; but, in our own way, we can emulate Martin: the common soldier.

And that is why we at Yankee Institute do what we do — because we cherish the liberties, here in our state and our nation — that so many people like Joseph Martin risked so much to give us. We must protect them in our time, for our fellow citizens and for those who follow us.

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler

What neat history do you have in your town? Send it to yours truly and I may end up highlighting it in a future edition of ‘Hidden in the Oak.’ Please encourage others to follow and subscribe to our newsletters and podcast, ‘Y CT Matters.’