An oilman. A U.S. Senator and judge. The founder of a magazine. American authors. These are only a few descriptors for the Buckleys, a family whose name is synonymous with intellectual dynamism, propensity for adventure, prolific output, satirical wit and, of course, American conservatism — embodied, particularly, by William (Bill) F. Buckley Jr. of National Review and Firing Line fame.

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, the Buckleys’ worldview shaped and continues to influence political thought and media, even so far as Robin Williams’ imitating Bill in Disney’s Aladdin. Yet Reid Buckley — one of William Sr. and Aloïse’s ten children — tries to downplay this significance in the opening pages of An American Family: The Buckleys, which chronicles the family’s history. He writes, “We were not Roosevelts. We were not Kennedys. There was no ‘mystique’ about us at all. We were an ordinary, though large and rambunctious, American family.”

They were certainly large, rambunctious and proud Americans. But they were hardly ordinary in their upbringing and individual legacies. Dan Seligman, who reviewed Bill’s autobiography Miles Gone By for Commentary magazine in October 2004, described the Buckleys’ childhood having a “distinctly aristocratic dimension.” Meanwhile, Thank You for Smoking satirical novelist Christopher Buckley — son of Bill and Patricia — recently told PBS in “The Incomparable Mr. Buckley,” the family was “raised in, I guess you could call it a bubble. It was sort of, you could call it Buckley World.”

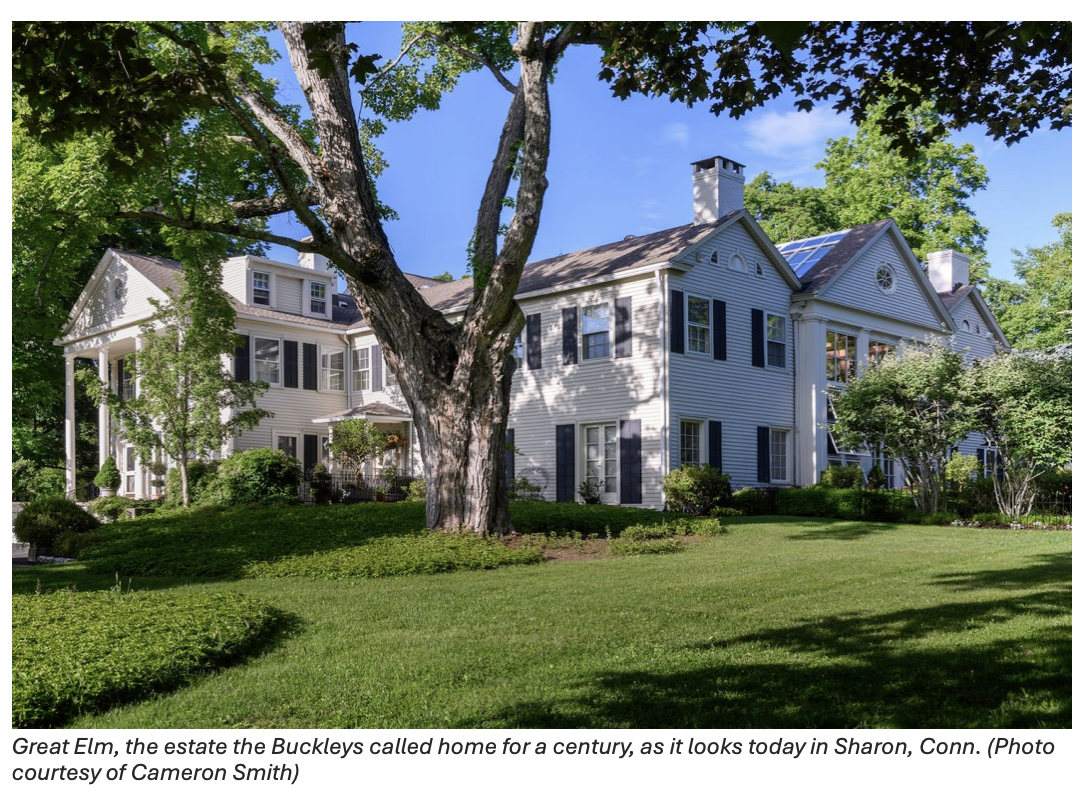

For more than a century, ‘Buckley World’ centered around the 50-acre estate in Sharon, Conn., that William Sr. purchased in 1923. Known as Great Elm, the property has undergone significant changes, expanding “into a sort of dormitory for [William Sr.’s] grandchildren,” as Priscilla Buckley — daughter of William Sr. and Aloïse, and former managing editor of National Review — wrote in “Buckley Branches” for Litchfield Magazine (March/April 2011).

However, the Georgian Colonial-style house is now for sale. The reason? “With Jim Buckley’s passing last year and 2023 having marked the 100th anniversary of grandfather buying Great Elm, my wife and I felt we had permission to relinquish stewardship,” Cameron Smith — Jane Buckley Smith’s son and William Sr.’s grandson — told Yankee Institute.

While Great Elm awaits new tenants, this is the story of how Sharon’s environment was instrumental in forming the philosophical tenets of the modern American conservative movement.

‘The Power and the Glory’

Indeed, there was a great elm on the property. In 1757, Rev. Cotton Smith planted the tree that eventually grew into one of the largest in Connecticut. Ansel Sterling, who settled in Sharon in 1809, christened the tree as “Sterling Elm,” according to An American Family: The Buckleys. It survived well into the 1950s, eventually succumbing to the Dutch Elm Disease that killed more than 70 million trees across America in the 20th century. When visiting the home in the early 1920s, William Sr. greatly admired the mighty tree, hence the estate’s current name.

In his historiography, Reid is “not sure” how his father discovered Sharon. And the Protestant, Yankee smalltown seemed an unlikely spot to settle a growing family for Catholic Southerners (William Sr. and Aloïse were born in Washington-on-the-Brazos, Texas and New Orleans, respectively). Nevertheless, the sprawling landscape seemed perfect to the Buckley patriarch.

The son of a sheriff, William Sr. was not born into luxury, growing up “in the sleepy frontier community of San Diego in South Texas,” according to William F. Buckley Sr.: Witness to the Mexican Revolution, 1908-1922 by John A. Adams Jr. He sought a life of education and adventure, moving to Mexico City after receiving his law degree from the University of Texas in 1907. Yet he arrived on “the eve of the revolution that forever changed his life and the course of Mexico for decades,” Adams states.

Initially, William Sr. and his brother Claude provided legal counsel to American, Mexican and British oil companies; however, with an oil boom in eastern Mexico in 1909, he expanded his horizons, “acquiring land and oil leases” and “maintain[ing] constant contact with local government officials, the president’s office, and the U.S. Embassy,” according to Adams’ biography.

During this time, William Sr. made a fortune that was stripped away during the Mexican Revolution (1910-20). The Mexican government did not take too kindly to his vehement opposition to its policies, particularly its anti-clerical (or anti-Catholic) laws. He not only financed Catholic groups fighting the oppressive regime, but also made diplomatic calls for more American intervention (as exemplified in his testimony before the U.S. Senate Joint Subcommittee on Foreign Relations in 1919).

As if his life were not full enough, William Sr. was also in “routine contact” with the revolutionary general Pancho Villa, “diplomats, businessmen, oil well drillers” and was even “captured by (and escaped from) bandits commissioned to murder him, and faced down snipers in the streets of Veracruz.” However, in 1921, the government expelled William Sr., his wife Aloïse — whom he married in 1917 — and their several children. He spent the next few years engaging with financiers in the United States and Europe to fund other oil expeditions.

In short, the Buckley patriarch’s experience in Mexico was certainly unique, and “defined” the rest of his life. It left a physical imprint on the Great Elm’s decor and furniture, of which “all been acquired in Mexico,” according to Reid Buckley’s An American Family: The Buckleys:

“The romantic and revolutionary Mexican background was everywhere shouted in Great Elm. Almost all doorways were framed by tiles across their tops and down their sides. All the principal bathrooms were faced or accented with tiles, and at the patio’s far southern terminus, just this side of the door, there is an Andalusian fountain…”

Even his children were not immune to their father’s Mexican days. As his son, James Buckley — a former U.S. senator and judge — describes in the forward of Adams’ biography:

“But what distinguished us most deeply was Mexico. It had somehow permeated our DNA. …he grew up with a total command of Spanish, and he was Catholic, he had especially close relationships with the Mexican community, relationships that in time developed into a love affair with their former country.”

But, more significantly (at least to the family’s future political commentators and leaders), the chaos William Sr. witnessed in Mexico made him deeply distrust government, which “indelibly stamp[ed] the assumptions, attitudes, perspectives, and political inclinations of his children, though each in his and her different manner,” as Reid Buckley states.

Standing Athwart History

The Great Elm, then, was a sanctuary of sorts for William Sr. — one where he and his wife could comfortably educate their children. He transformed the home, initially built in 1812, into a compound with “almost all the advantages of indoor and outdoor family life,” according to W.F.B. —An Appreciation by Priscilla.

All the children were homeschooled. In Miles Gone By, Bill Buckley recalls how he and his siblings were taught various languages, such as French and Spanish, and learned how to play instruments, particularly American and Mexican folk songs, which his father enjoyed. The house had five pianos, and the Buckley children “found ourselves divided into mandolin players (two), banjo players (two), guitar players (two), and ukulele players (one) (my six-year-old sister).”

Horse riding and shows were another crucial aspect of their education at Great Elm. As Bill writes, “No day went by at our place without two or three hours’ wandering about through the woods and pastures, sometimes at full gallop.” In a family anecdote, his sister Maureen won a blue ribbon at a horse show, and in attendance was President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who gave her an ovation. She ignored the adulation.

There was a balance of exploration and regimen to the Buckleys’ education between horse riding, musical tutoring and sailing, as Bill writes in Miles Gone By. In truth, their “academics required no radical departures from our way of life and none at all from our surroundings, because we were taught by tutors right there in the same rooms in which we played when indoors during the summer.” He expands on the children’s routine, saying:

“When school began for us at the end of September, we continued to ride on horseback every afternoon, we swam two or three times every day until the water got too cold, our musical tutors continued to come to us just as they had done during the summer, and some of us would rise early and hunt pheasants at our farm before school; our classes began at 8:30 and ended at noon, and there would be study hall and music appreciation between 4:00 and 6:00.”

In “The Incomparable Mr. Buckley,” historian Kevin M. Schultz, author of Buckley and Mailer: The Difficult Friendship That Shaped the Sixties, summarizes that “Great Elm was a world unto itself,” noting that “Nobody had to go outside of the walls in order to encounter any part of life.” For that reason, he further states that the “family was unbelievably insular.” Even James Buckley admits in William F. Buckley Sr.: Witness to the Mexican Revolution, 1908-1922 that “we were very conscious of being significantly different from our friends and neighbors.”

But Sharon encouraged such an education with its natural wonders and space, and even served as a crucible for imparting the Catholic faith, “fervent anticommunism, and steadfast opposition to government interference in the economy,” as Matthew Continetti notes in The Right: The Hundred Year War for American Conservatism. William Sr. and Aloïse’s personalities also kindled a deep camaraderie among the siblings to an “astonishing degree,” as Reid Buckley recounts, adding that “the solidarity our parents fostered in their children was remarkable. God, family, country…and in that order.”

Among the more influential visitors to Great Elm was Albert Jay Nock, who promoted “individualism, anti-statism, and the Remnant—those few souls who could preserve the wisdom and practices of Western civilization during the approaching dark age,” according to The Right. Bill Buckley gravitated toward Nock’s ideas and “ingrained” them, which shaped his life’s work, as Continetti suggests.

Beyond being a hub for family life, Great Elm served as a meeting place for one of the most consequential events in the American conservative movement. In early September 1960, frustrated by leftist-liberalism and communistic influence on college campuses, nearly 100 students from 44 colleges in 24 states gathered in Sharon under Bill’s auspices — who, by that time, had published God & Man at Yale (1951) and founded National Review (1955) — to define conservative principles and enumerate them into a single document. What these students produced was “The Sharon Statement” and Young Americans for Freedom (YAF), an organization “committed to ensuring that increasing numbers of young Americans understand and are inspired by the ideas of individual freedom, a strong national defense, free enterprise, and traditional values.”

The statement, which was described by the New York Times as a “seminal document in bringing different kinds of conservatives together,” affirmed “certain eternal truths” about “God-given free will,” that “political freedom cannot long exist without economic freedom,” that the “Constitution of the United States is the best arrangement yet devised for empowering government to fulfill its proper role,” and that the “forces of international Communism are, at present, the greatest single threat to these liberties,” among other assertions.

The Sharon Statement and YAF would play a “key role” in Barry Goldwater’s 1964 Presidential campaign, and later Ronald Reagan’s ascendancy to the presidency. (Reagan joined the YAF National Advisory Board in 1962.) Today, YAF chapters are on more than 2,000 campuses; and a plaque at Great Elm commemorates the spot where the students met.

Only Great Elm — and Bill’s tutelage — could have provided the conditions necessary to ignite an ideological movement that still impacts modern politics.

‘God, Family, Country…’

Great Elm has not been resistant to change. When William Sr. first purchased the property, the estate had a “two-storey home, barns and stables, a tenant’s cottage, and an icehouse,” according to Priscilla’s “Buckley Branches.” Under his direction, William Sr. commissioned the construction of a closed-in atrium with brightly colored tiles and wrought iron railings “to make the space reminiscent of New Orleans” to honor Aloïse’s roots, as Cameron Smith told Mansion Global; additionally, other homes were built on the property — where Priscilla and James lived — to accommodate the large family.

William Sr. passed away on Oct. 5, 1958, at 77 years old. Aloïse died on March 10, 1985, at 89 in the Buckley house. At the time of her death, she was survived by 50 grandchildren and 33 great-grandchildren. Still, the Sharon home served as the “family heartland,” according to Priscilla’s “Buckley Branches.”

During the 1980s, the Buckley family originally planned to convert Great Elm into an elder care community, but the application was denied by Sharon’s Zoning Board of Appeals. Instead, the family turned the property into a homeowners’ association (Great Elm Community, Inc.), comprised of eight condominiums and nine free-standing homes.

However, all of the children have passed away, the last being James, who died at 100 years old on Aug. 18, 2023. Most are buried in the family plot in St. Bernard Cemetery in Sharon.

So why this house? People are a product of their families and environment. The Buckleys were ordinary in that regard. More significantly, as Rich Lowry, editor of National Review, succinctly encapsulates, Great Elm is “inextricably caught up in American political history.”

This home fostered one of the most consequential movements of the 20th and 21st centuries. To think Connecticut’s beautiful landscape had a role in informing the modern political landscape is indeed worthy of protecting, regardless of ideological affiliation. It is something to be preserved and studied for future generations.

Hopefully Great Elm’s next stewards will recognize that.

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler

More personally, without Great Elm and the Buckleys, I would certainly have had a different path in life. My father worked at National Review for more than a quarter century — and he is proud to have called Bill a friend. In light of the news (i.e., the house being up for sale), I visited Great Elm, thanks to Cameron Smith. I got to see what Bill saw. Sharon is a beautiful town, with rolling vistas, a quaint town-center, yet a deep-rooted history harkening back to the Revolutionary War. Visiting places offers a new perspective — and a new understanding of how we are linked to the land from which we’ve grown up. It’s my hope that new tenants, whoever they may be, preserve Great Elm’s majesty.

What neat history do you have in your town? Send it to yours truly and I may end up highlighting it in a future edition of ‘Hidden in the Oak.’ Please encourage others to follow and subscribe to our newsletters and podcast, ‘Y CT Matters.’