The Articles of Confederation were not effective. Adopted by the Continental Congress in 1777 during the American Revolution, the nation’s first governing document “faced many challenges in conducting foreign policy, largely due to its inability to pass or enforce laws that individual states found counter to their interests,” according to the U.S. State Department’s Office of the Historian.

In the war’s aftermath, each state acted more or less independently, tenuously linked to a feeble central authority, whose power was purposefully limited by the wary former colonists to prevent the rise of an oppressive government like the British Parliament they had just defeated.

However, as explained by the National Archives, “disputes over territory, war pensions, taxation, and trade” carried the 13 states to “the brink of economic disaster” that “threatened to tear the country apart.”

The issues had to be resolved lest the country perish. Therefore, in May 1787, delegates from every state — except Rhode Island — gathered in Philadelphia with the goal of revamping the Articles of Confederation. Instead, they emerged with a new governing document, the U.S. Constitution, which was drafted and later ratified by the attendees.

Connecticut was represented by three distinguished men: Roger Sherman, who signed the Declaration of Independence and, at that time, served as New Haven’s first mayor; Oliver Ellsworth, a delegate to the Continental Congress during the Revolution and a state judge; and William Samuel Johnson, a former militia officer and representative to the Congress of the Confederation (1785-1787). Although modern Americans celebrate great men like James Madison and Alexander Hamilton (and rightly so), the three Connecticut delegates arguably proved the most instrumental in the new constitution’s adoption, offering a compromise that finally broke a “deadlock” concerning the central government’s legislative body.

The men’s contributions were not restricted to Philadelphia, as all three advocated for and shepherded the Constitution’s eventual ratification by Connecticut’s state legislature (Jan. 9, 1788). This is the story of Connecticut’s indelible mark on the U.S. Constitution, and how it became the fifth state in the new — and current — union.

Connecticut at the Constitutional Convention

On May 28, 1787, Ellsworth arrived in Philadelphia, the first delegate from Connecticut to do so. His colleagues Sherman and Johnson would appear on May 30 and June 2, respectively. Like others at the Convention, Sherman “originally favored strengthening the Articles of Confederation,” having drafted amendments to give the Continental Congress “power to levy imports, to establish a supreme court, and to make laws binding on all the people,” according to the U.S. Army Center of Military History.

Meanwhile, Johnson — who missed no sessions, becoming one of the more respected delegates at the time — vied for a stronger federal government “to protect the rights of Connecticut and the other small states from encroachment by their more powerful neighbors.” And Ellsworth, as noted in the Convention’s Minutes, desired to “build our Genl. Govt. [sic] upon the vigour & strength of the State Govts,” openly advocating for a legislative body that would be elected by each respective state legislature.

Quite quickly, the Convention’s debate shifted from amending the Articles of Confederation to creating a new, “highly centralized” federal government. The first proposed outline was drafted by the Virginia delegates — aptly named the Virginia Plan. In it, the three branches (legislative, executive and judicial) would not only check one another’s power and be elected through proportional representation, but the system would also “have veto power over laws enacted by state legislatures,” according to the National Archives. Members of smaller states, which included Connecticut, rejected the concept, believing the plan endangered state sovereignty. As Sherman stated, the proposal “gives the power to four states to govern nine states.”

Other proposals introduced, such as the New Jersey Plan, protected smaller states by “limiting each state to one vote in Congress, as under the Articles of Confederation.” However, the Convention also rejected that plan.

During that summer, Ellsworth had become one of the more active delegates, second only to Madison and Gouverneur Morris, in debates (particularly between July 26 and August 6). His influential oratory skill even squashed the removal of ‘United States’ in the country’s official title. It must be noted that he favored the three-fifths compromise “on the enumeration of slaves but opposed the abolition of the foreign slave trade,” according to the National Archives. Yet his — and Sherman’s — greatest influence at the Convention came in mid-July. After discussions reached a breaking point on the legislature’s structure that “threatened to destroy the seven-week-old convention,” the pair devised the Connecticut Compromise and presented it on July 16.

The plan proposed a bicameral legislature to balance the interests of both larger and smaller states: in the lower chamber, the House of Representatives, each state’s number of seats would be determined by population (i.e., proportional representation); while the upper chamber, the Senate, would have equal representation from each state. This is the current system Americans know today, but it almost never came to be, as it was adopted by only a one-vote margin.

Nevertheless, with the successful vote, Ellsworth and Sherman solidified their legacies at the Convention and in American history by engineering what is now referred to as ‘The Great Compromise.’

For the rest of the Convention, which ended on Sept. 17, 1787, Ellsworth served on the Committee of Five — along with John Rutledge, Nathaniel Gorham, Edmund Randolph and James Wilson — to write a first draft of the U.S. Constitution. However, he was “forced to leave Philadelphia for business reasons before signing the final document,” according to the National Constitution Center. Meanwhile, Johnson, who defended his colleagues’ compromise, was selected to chair the Committee of Style. In his duties, the five-person team polished a nearly final draft in about three days, which was submitted for approval on September 12.

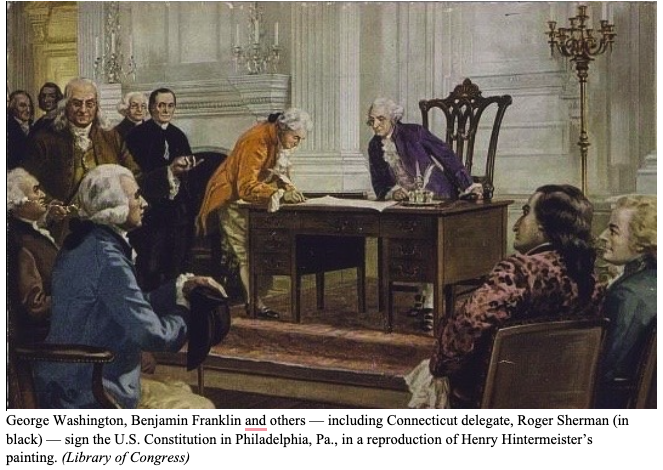

Sherman, for his part, signed the Constitution’s final draft, making him the only person to sign “all four of the important American Revolutionary documents,” which included the Articles of Association (1774), the Declaration of Independence (1776) and the Articles of Confederation (1781).

In the end, 39 out of 55 delegates signed the U.S. Constitution; however, its adoption in Philadelphia was only a harbinger of the ensuing debates in each state, as the new governing document needed to be ratified by nine state legislatures in order to be implemented. In Connecticut, Ellsworth, Sherman and Johnson spearheaded its advocacy — but the task was not easy.

Replacing the Old System

In the fall of 1787, the three Connecticut gentlemen returned home to shepherd the U.S. Constitution’s ratification in the state legislature — a document that, more than likely, would not exist without their compromise. Yet residents were not united in support. According to ConnecticutHistory.org:

“…the dividing line typically placed merchants and those of the wealthier, more urbane social strata in opposition to farmers and those from rural areas. The former, seeking stronger trade protections that a centralized government could bring, supported adoption of the Constitution; the latter, wary of federal taxation and the institution of a new merchant-aristocracy, viewed it with skepticism.”

Both classes would have to be convinced. Ellsworth took the lead, writing the “Letters from a Landholder” series (composed of 13 letters) to address concerns largely waged by skeptics, even from neighboring states, such as Elbridge Gerry — a Massachusetts delegate to the Constitutional Convention. Ellsworth’s articles were akin to the Federalist Papers penned by Madison, Hamilton and John Jay, in which he argued the new constitution would preserve liberty (particularly religious freedom), domestic and foreign trade, national security and, more importantly, the union itself.

“This is the last opportunity you may have to adopt a government which gives all protection of personal liberty, and at the same time promises fair to afford you all the advantages of a sovereign empire,” he writes in the second letter (Nov. 12, 1787); and in the third (Nov. 19, 1787), he states, “The new Constitution is perhaps more cautiously guarded than any other in the world, and at the same time creates a power which will be able to protect the subject.”

Other major objections were rooted in a lack of a ‘bill of rights’ and state sovereignty, both of which Sherman explored in his own defense known as “A Countryman” letters, posted in the New Haven Gazette between November 14-December 20. In the second editorial, the Founding Father reasoned that despite a bill of rights in the state constitution, the General Assembly could have “enact[ed] that the subjects should enjoy none of those privileges,” but restrained itself because the legislature “were as strongly interested in preserving those rights as any of the subjects.” Therefore, he concludes, that the U.S. Congress would act likewise, writing, “If the members of Congress can take no improper step which will not affect them as much as it does us, we need not apprehend that they will usurp authorities not given them to injure that society of which they are a part.” Meanwhile, he highlighted how frequent elections would curb the centralized government’s power by comparing the Constitution to Parliament. He rhetorically asks, “Are not the liberties of the people of England as safe as yours? — They are not as free as yours, because much of their government is in the hands of hereditary majesty and nobility.”

After much back-and-forth in the press, Connecticut lawmakers opened the ratifying convention in Hartford on Jan. 4, 1788. Ellsworth and Johnson were the Constitution’s primary defenders that day, offering their last pitch to attendees.

In the former’s speech, he stressed national security from foreign adversaries, saying:

“United, we are strong; divided we are weak. It is easy for hostile nations to sweep off a number of separate states one after another. …If a war breaks out, and our situation invites our enemies to make war, how are we to defend ourselves? Has Government the means to enlist a man, or buy an ox? Or shall we rally the remainder of our old army?”

Ellsworth feared Europe, believing the nations to be “not friendly to us” and “pleased to see us disunited among ourselves.” With a new constitution, a stronger federal government would prevent European powers from “play[ing] the States off one against another,” and entangling Americans in “all the labyrinths of European politics.” He warned that if the states rejected the Constitution, they risked the fate suffered by ancient and European nations, who were easily conquered for not uniting.

However, the Constitution would not only thwart conflicts with Europe, but “preserve peace” among the states at home. As Ellsworth said:

“States, as well as individuals, are subject to ambition, to avarice, to those jarring passions which disturb the peace of society. What is to check these? If there is a parental hand over the whole, this, and nothing else, can restrain the unruly conduct of the members. Union is necessary to preserve commutative justice between the states. If divided, what is to hinder the large states from oppressing the small?”

While not as long as his colleague’s speech, Johnson’s tone was nonetheless dire and urgent, saying:

“Our commerce is annihilated; our national honour, once in so high esteem, is no more. We have got to the very brink of ruin; we must turn back, and adopt a new system. …If we reject a plan of government which with such favourable circumstances is offered for our acceptance, I fear our national existence must come to a final end.”

Ultimately, the arguments were persuasive. On January 9, Connecticut ratified the Constitution — by a vote of 128-40 — becoming the fifth state in the union to do so.

‘We the People…’

The Unites States of America officially began operating under the Constitution on March 9, 1789 — though North Carolina and Rhode Island would not ratify it until Nov. 21, 1789, and May 29, 1790, respectively.

Meanwhile, the three Connecticut delegates continued their distinguished careers, taking an active part in the new system they were vital in implementing. Johnson served as one of Connecticut’s first U.S. Senators until his resignation on March 3, 1791, after the capital moved from New York to Philadelphia. Instead, he “preferred to devote all his energies to the presidency of Columbia College” which he did until 1800. He died at 92 on Nov. 14, 1819.

Sherman was elected to Congress (1789-1791), and then was appointed to take Johnson’s vacant seat in the Senate (1791-93). However, his term was cut short, as he passed away at 72 in New Haven on July 23, 1793.

Ellsworth was, perhaps, the most involved in the early days of the American Republic: alongside Johnson, he was one of the first two U.S. Senators (1789-1796). His most significant legislative accomplishment was authoring the Judiciary Act of 1789 — a law that “defined the structure and jurisdiction of the federal court system” that “remains largely intact today,” according to the Constitution Center. In early 1796, President George Washington nominated Ellsworth as the third chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, and he was unanimously confirmed. Simultaneously, he was appointed as a commissioner to negotiate peaceful trade terms with Napoleon Bonaparte’s French government. After resigning from the Supreme Court due to poor health, Ellsworth retired and returned to his hometown, Windsor. He died on Nov. 26, 1807, at 62.

It is unquestionable that the three men left an indelible mark on America. Yet, as noted earlier, their service in the wider collective consciousness has been relegated to the proverbial backburner. But without the Connecticut Compromise, the convention might have remained deadlocked, which, in turn, could have led to the country’s disintegration. The situation was that dire; Sherman, Ellsworth and Johnson rose to the occasion, however, establishing the constitutional structure that has allowed our nation to thrive.

On this anniversary of Connecticut’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution, let us not take them for granted. Let us remember their names.

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler