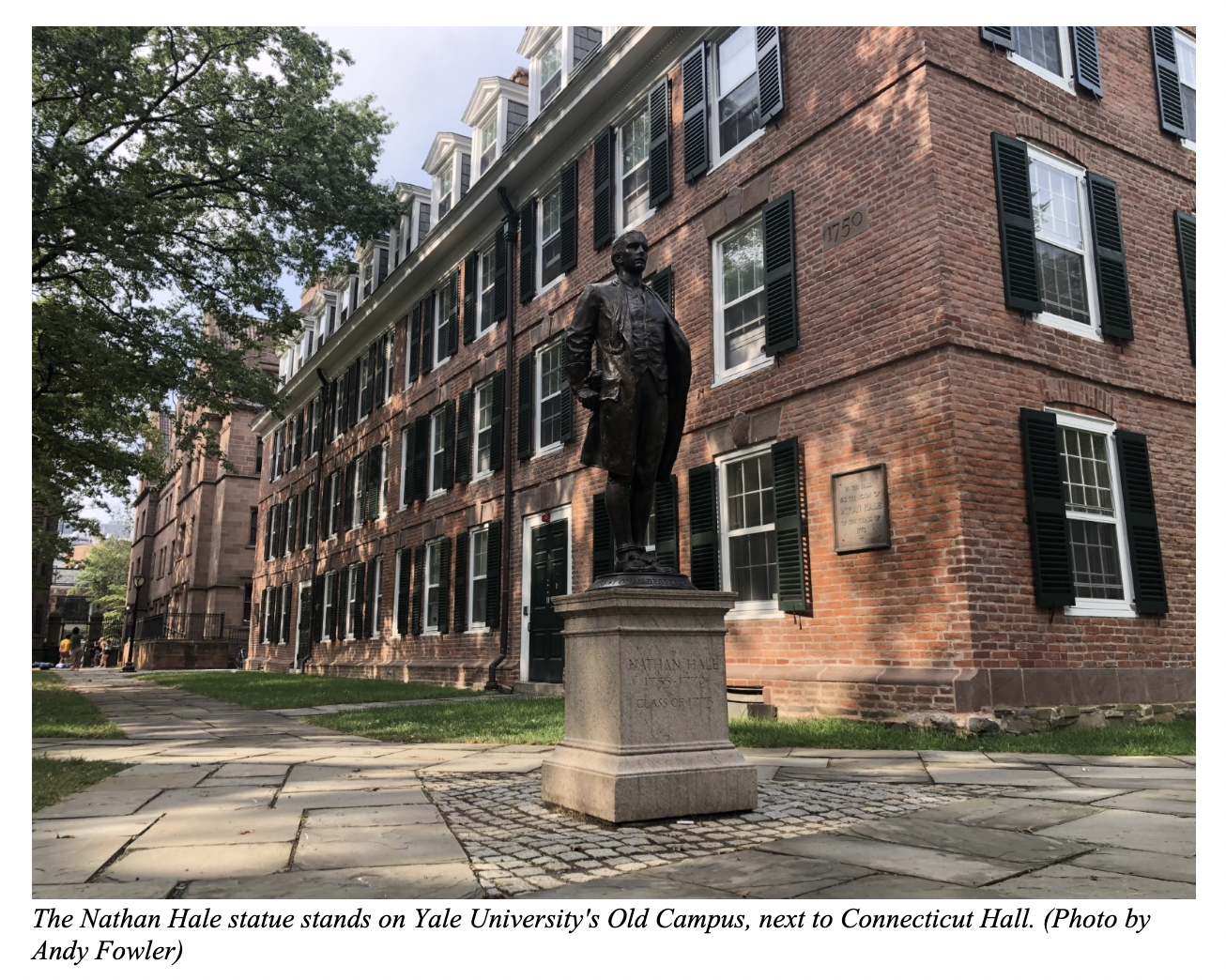

In Yale University’s Old Campus, next to Connecticut Hall, stands a larger-than-life-sized bronze statue of the American Revolutionary War hero and alum Nathan Hale — a 21-year-old Connecticut native executed by the British for spying on Sept. 22, 1776. The statue depicts him moments before his death with hands and feet bound.

Yet Hale’s face and stance are defiant, as his mouth appears to utter his final words, which have become one of most famous lines in American history: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.” Whether he said these words verbatim is uncertain; nevertheless, Hale’s “composure and resolution” at the gallows — as a British officer and eyewitness attested — encapsulated the burgeoning Revolutionary spirit in the early throes of the war.

Since then, Hale has become synonymous with American patriotism and a “symbol of selfless sacrifice in the service of his country,” according to ConnecticutHistory.org. He is even Connecticut’s official “State Hero” by an act of the General Assembly on Oct. 1, 1985.

Although Yale has certainly had its share of noteworthy alumni (from U.S. presidents, Supreme Court justices, authors, TV and film personalities), Hale ranks highly in that pantheon. However, nearly 150 years after his legendary, almost mythic death, the patriot’s alma mater had yet to honor its Revolutionary War hero — until a movement in the late 1880s.

Even with enthusiasm behind the project, the statue took nearly 15 years from inception to completion, when it was finally dedicated in the fall of 1914. This is the story of the Yale graduate and the long, winding road of how the statue came to be.

From School Teacher to Spy

Nathan Hale was born June 6, 1755, in Coventry, the sixth of Deacon Richard and Elizabeth Hale’s 12 children. At 14, he and his brother, Enoch, were sent to Yale where the future spy “was among the thirteen scholars of highest rank in his class,” according to a history written by his grand-nephew, Rev. Edward Everett Hale.

While attending Yale, Hale reportedly lived in Connecticut Hall, was interested in theatrical performances, belonged to the Linonian Society (a literary and debate group that disbanded in 1868), and “successfully argu[ed] during his commencement debates in favor of equal education for women,” nearly 200 years before the university officially became co-ed, according to Yale.

After graduating in 1773, Hale became a teacher in an East Haddam school, but then “obtained a better position at a private academy in New London” the following year. Then the “shot heard around the world” was fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in early April 1775, forever changing the course of Hale’s young life. According to his grand-nephew’s history, Hale spoke at a New London town meeting, saying, “Let us march immediately,” adding, “Never lay down our arms until we obtain our independence.”

Again, whether those statements are true or invented does not detract from the fact that Hale was moved to act by the revolutionary cause, officially enlisting in the militia on July 6, 1775. He served with the Seventh Connecticut Regiment as a first lieutenant at the Battle of Bunker Hill, which was in a “state of stalemate” when he arrived. After the British evacuated Boston March 17, 1776, General George Washington moved the Continental Army to Manhattan, believing New York would be the next focus of attack — which proved correct.

On Aug. 27, 1776, the Continental Army suffered a humiliating blow in the Battle of Brookyln Heights, as the British gained a foothold on Long Island, taking the Port of New York. Convinced of another imminent attack, Washington asked Lt. Col. Thomas Knowlton — who led a reconnaissance outfit known as Knowlton’s Rangers — for a volunteer to slip behind enemy lines and gather intelligence. When Knowlton later presented the mission to officers, most were hesitant because spying was beneath a gentleman. However, Hale (at that point a captain) “broke the silence” and offered his services for he “saw an opportunity to serve, and he did the duty which came next at hand,” according to Rev. Hale. He began his spying duties on Sept. 8.

Hale disguised himself as a Dutch schoolmaster — in a “plain brown suit and a round hat” — and successfully gathered information about British movements for several weeks, according to History.com. Then on the windy night of Sept. 20, a “mysterious fire” started at the “southern tip of Manhattan and burned until dawn, consuming most of the town between Broadway and the Hudson River,” according to Ron Chernow’s Washington: A Life. The British were inflamed by the pandemonium and wreckage (more than 500 homes and a quarter of the town was destroyed), and believed the revolutionaries committed arson. However, Chernow notes that the British “never found convincing proof to corroborate their suspicion of patriotic involvement.”

Nevertheless, Hale was swept up in the vengeful detentions — along with more than a hundred sympathizers to the American cause — when he was stopped en route to Long Island by a company of Loyalists. Reports vary on how he “aroused suspicion,” including one in which he was recognized by a Connecticut shopkeeper and Loyalist, and another that he was betrayed by his cousin, Samuel Hale. Whatever the case, Hale’s ruse was up when Gen. William Howe found papers on him during an interrogation. Howe ordered Hale’s execution for the following morning. The Yale graduate spent his final night confined in the garden greenhouse at Howe’s headquarters on First Avenue and 51st Street.

The next day, Sept. 22, Hale was permitted to write two letters — one to his mother and one to his brother, Enoch — although these were destroyed. Before his execution, he requested a Bible, but was refused. He was then led to the artillery park at Third Avenue and 66th Street, where he was hanged from a tree.

As for his famous last words? According to American Capt. William Hull’s memoirs, British engineer John Montresor — who was present at the execution — told him the next day of Hale’s words, and the patriot’s “calm” and “gentle dignity, in the consciousness of rectitude and high intentions.” Meanwhile, scholars believe Hale paraphrased a passage from Joseph Addison’s 1712 play Cato, which reads: “What pity is it/That we can die but once to serve our country.”

The Memorial at Yale

More than a hundred years after Nathan Hale’s martyrdom for the American cause, there was a surge in statues honoring the Revolutionary War hero. In 1886, Connecticut dedicated a bronze statue of him — designed by Karl Gerhardt — in the state capitol. In 1893, the “Sons of the Revolution” erected its own Hale statue by Frederick W. MacMonnies that currently resides in Manhattan’s City Hall Park. The latter project, as reported by the Yale Daily News, took nearly five years to complete.

The first rumblings of Yale honoring its graduate appeared in the Yale Daily News, dated June 22, 1887: “The Nathan Hale Statue ‘boom’ is spreading,” the unattributed blurb stated, adding, “It is now proposed that Yale, the patriot’s alma mater, erect a monument to his memory on the college campus.”

The next day, the News reprinted a letter by ‘R.’ to the Hartford Times’ editor advocating that the “friends of Yale secure a statue” because “A great many under-graduates here do not know that this hero of Connecticut was a student at this college, and a statue in his honor evidently would be the most substantial way of reminding all who come upon the campus of this fact.”

Yale took its time, yet enthusiasm remained as indicated by an entry in the News from March 3, 1899, which reads:

“Nathan Hale is the type of men that Yale glories in, and that makes Yale glorious. Courage, loyalty and the qualities of a true gentleman, all so strongly blended in this man’s character, are the lessons which Yale is still teaching today. What more appropriate form could a memorial take than the proposed monument to our dead soldiers; and what more fitting statue could crown it than that of Nathan Hale of 1773?”

By March 17, the Yale Corporation — the university’s governing body — approved the placement of a statue of Hale on campus, to be led by a committee that included Joseph Hawley (the 42nd Governor of Connecticut and U.S. Senator), Prof. John Ferguson Weir (first director of the School of Fine Arts at Yale) and Rev. Theodore T. Munger, among others. In reaction, the News praised the development, saying it would “give all the aid in its power to further the interests of the project.” Indeed, the project moved smoothly as the committee held its first meeting a month later with the aim of dedicating the statue before the university’s bicentennial in 1901.

However, eleven months passed and no further report to the Corporation was given, according to the News, Feb. 28, 1900. The editors “fail[ed] to see the reason for so long a delay,” adding that “If the committee is not more expeditious, it is doubtful if the mere plans will be much more than formulated by the time of the Bi-centennial celebration.”

Their doubts were realized. The bicentennial came and went with no statue — yet there were several issues contributing to the delay. As reported by the News (Feb. 9, 1901), the initial committee was asked by “persons in charge of the Bicentennial fund” to postpone fundraising for the project until the “Bicentennial fund was secured.” To complicate matters, there was an unauthorized, separate movement organized by “a large body of Yale alumni and other friends of the University” to erect a statue designed by William Ordway Partridge, and gift it to the school by the bicentennial. As to why this Partridge movement came to be — especially three years prior to 1901 — is uncertain, at least until Peter Flint (class of 1880) explained in the News more than 10 years later; regardless, by May 1901, the official committee members submitted a resolution asking to be “discharged” from their duties and noting “that the Corporation, pending other plans, will not consider the assignment of a location on the College Campus for any statue.”

Therefore, a statue was not dedicated, and frustration brewed as indicated by a representative of the Hale Executive Committee Yale Alumni, who stated in the News that “every year of delay or indifference is intensifying the dishonor we are showing to the memory of Nathan Hale.”

Despite the setbacks, the Partridge movement — chaired by Flint — continued its efforts, offering a design in June 1908; yet the Yale Corporation deferred a “formal acceptance” until “some other movements, then stated by the Corporation to be under way or in contemplation in this direction, had been investigated or discontinued.” Flint asserted in his April 28, 1911, letter to the News that other efforts had disbanded, so the Partridge movement was “now open for the completion of the original Alumni undertaking.” He solicited all Yale graduates to “combine in the movement” to pay the cost of $20,000 (or more than $600,000 today) for the statue.

Yet misfortune struck again in the “long drawn-out controversy” as Partridge withdrew his proposed designs as reported by the News on Oct. 31, 1911. The News did not report why the sculptor abandoned the project.

It seemed like a statue honoring Connecticut’s state hero would remain in development hell. More than ten years had passed since the concept’s official inception. However, by late 1912, Yale authorities took another swing, giving permission to a committee — one that included George Dudley Seymour, an attorney known as the foremost expert on Hale at the time — to erect a statue designed by Bela Lyon Pratt, a sculptor who had studied at the college’s School of Fine Arts.

The effort gained traction with a sketch-model appearing in the Nov. 16, 1912, edition of the News. However, Pratt faced several issues too. First, as the Nov. 16 article noted, there had never been an “existing portrait of Nathan Hale” and that “the miniature once owned by his fiancée disappeared long ago.” Instead, the artist “studied a portrait furnished him by the late Rev. Edward Everett Hale of one of his sons who died at about Hale’s age.” He also wanted to “avoid giving the statue a grandiose character,” saying that “students of today, as they pass back and forth, will feel that Hale is one of them — one of them in every way, but happily removed from the tumult of life, from loss and stain, and forever bright.” Meanwhile, the Yale Corporation initially raised doubts of depicting Hale “bound with ropes” but these “objections were later overcome,” according to the News dated Oct. 2, 1914.

By October 1914, the long-awaited statue had finally been placed next to Connecticut Hall — and stands there today.

A Patriotic Heart

The Nathan Hale memorial took 15 years from inception to completion, more than half the length of the patriot’s life. A few years later, millions of young, American men — similar in age to Hale when he died — answered the call of duty to serve their country overseas in World War I.

Meanwhile, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) honored one of America’s earliest spies with a replica of Yale’s statue, unveiling it at the Langley headquarters on June 6, 1973, the bicentennial of Hale’s graduation from the university (although there is also a rumor that the CIA stole the original…). According to CIA tradition, officers will place a quarter or 76 cents around the statue to ensure their safety before leaving for an assignment.

Today, Yale’s long, winding road to commemorating this hero of the American Revolution might not provoke much thought on the part of visitors, students or passersby. Perhaps they simply do not know the story. But as this author will attest by virtue of a recent visit, the statue serves its purpose, as tour guides will point out Hale and note his heroism.

These tangible reminders of our forefathers present an opportunity to reflect on how far this nation has come — and the price for the freedoms we have inherited. Prior to the presence of Hale’s statue, as Flint wrote in his 1911 letter, “Personally, I never heard the name of Nathan Hale mentioned during my college days, and I was often asked in the early part of this movement by Yale men whether Nathan Hale was indeed a graduate of Yale College.”

But Hale was flesh and blood, not bronze or slightly larger than life. He was a young man who made the ultimate sacrifice for an ideal he never lived to see fulfilled. Upon looking at the statue, as Hale looks out to the horizon uttering his final words, we must ask ourselves: do we have the courage likewise to stake our lives on the principles we hold dear?

Till next time —

Your Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Andy Fowler

Appendix I: Nathan Hale’s legacy is important to Yankee Institute — a painting of Hale’s defiance prior to his execution hangs in our conference room, to remind us of the sacrifices our forefathers made for our freedom and to honor our Connecticut heritage. Again, art is meant to draw our attention to aim for our shared, higher ideals.

Appendix II: One of Connecticut’s landmarks is the Nathan Hale Homestead in Coventry. If you want to learn more about Hale, it might be time to make the pilgrimage. Learn more about the Homestead here.

What neat history do you have in your town? Send it to yours truly and I may end up highlighting it in a future edition of ‘Hidden in the Oak.’ Please encourage others to follow and subscribe to our newsletters and podcast, ‘Y CT Matters.’