Hartford is among the worst cities regarding office delinquency rates in the nation, and the city also continues to suffer from increasing office building vacancy rates (now nearly at 30%), according to two separate, recent reports.

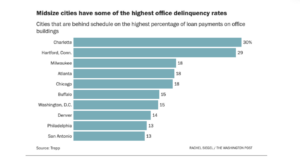

“The average delinquency rate across the 50 largest metro areas in the country is about 5 percent,” writes Rachel Siegel in “The Washington Post.” “But in places like Charlotte in North Carolina or Hartford in Connecticut, it is almost 30 percent, according to data from the real estate analytics company Trepp.”

Meanwhile, CBRE — a global leader in commercial real estate services and investment — found in its “Hartford County Office Figures Q2 2023” study that the greater Hartford market “remained largely unchanged from [the] prior quarter”; however, the vacancy rate in the previous quarter dangled at 23.7%, which is now at 28.2%. Meanwhile, the market had “narrowly positive” absorption rate (i.e., more tenants leasing available office spaces) at 42,000 sq. ft.

“Downtown Hartford — which captured the largest transaction of the quarter, with the City of Hartford’s 28,000-sq.-ft. relocation to 280 Trumbull Street — drove positive absorption in contrast to suburban Hartford, which counter-balanced with negative absorption in the second quarter,” CBRE reported.

The study analyzed absorption rates in several submarkets: the City of Hartford; Hartford North (Bloomfield, East Granby, East Windsor, Enfield, Windsor and Windsor Locks); Hartford East (East Harford and Glastonbury); Hartford South (New Britain, Newington, Rocky Hill and Wethersfield); and Hartford West (Avon, Farmington, Simsbury, Southington and West Hartford). The City of Hartford experienced the highest absorption rate, while Hartford North suffered the worst negative absorption of 76,000 sq. ft.

But none of these findings bode well for the state capitol — especially considering WalletHub’s report that Hartford is one of the worst run cities in America — or for the nation.

“All across the country, downtowns, office spaces and shopping centers are at risk of becoming ground zero for a new economic hazard: the urban doom loop,” Siegel writes for the Post. “The fear is that a commercial real estate apocalypse could spiral out and slow commerce, wrecking local tax revenue in the process.”

She adds, “But many economists are even more worried about midsize cities that have fewer ways to offset the blow when a major company slashes office space, the sale price of a building craters, or a downtown turns into a ghost town.”

The urban doom loop scenario is as such: with fewer commuters and businesses in a city, the peripheral businesses (i.e., restaurants, bars, stores) would suffer and close-up shop — which, in turn, decreases tax revenue from the commercial properties or employee wages, thereby negatively impacting government services and the economic well-being of the community as a whole.

But Hartford’s recent troubles may not spell doom in the immediate future as “many cities are still leaning on historic levels of state and local stimulus aid from the 2021 American Rescue Plan, and those funds may not run out for another year or two,” the Post suggests, adding that “A large share of the outstanding business and mortgage loans are also not due for a few more years.”

However, those funds cannot be depended on for the long-term; and Hartford’s situation is unlikely to reverse course overnight, neither is the state overall, which continues to rank poorly among corporate tax rates. The state also, recently, received D grades in ‘Economy’ and ‘Cost of Doing Business’ by CNBC’s “America’s Top States for Business.”

Connecticut lawmakers need to get ahead of the vacancy issue by offering more lessening the tax burdens on the state’s families and businesses, to entice them to move here — and stay.

But with news of CVS laying off more than 500 employees and Frontier Communications rumored to join the corporate exodus from Connecticut, the state is trending in the wrong direction.