Eight score ago, the Union and Confederate armies clashed in the crossroads, farm town of Gettysburg, Pa., in a three-day conflict (July 1-3) that became the bloodiest battle in the American Civil War.

Out of the 165,000 who fought, more than 51,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or went missing and/or captured. But the Union victory, led by Gen. George Meade, marked a turning point in the war by stonewalling Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s push into northern territory, forcing him to retreat below the Mason-Dixon Line.

For the rest of the war, the Confederacy primarily remained on the defensive, while their prospects of forming an independent nation continuously diminished until Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

But among the “brave men, living and dead, who struggled here” — as President Abraham Lincoln would describe them in the Gettysburg Address — nearly 1,270 were from Connecticut, comprised in the 2nd Artillery, as well as the 5th, 14th, 17th, 20th and 27th Volunteer Infantry Regiments.

This is the story of what those men endured and the pivotal role they played in the Union victory.

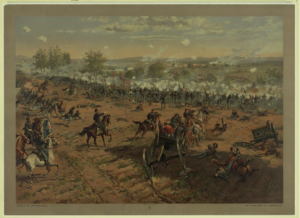

A print depicts Union troops advancing from the right during the Battle of Gettysburg. (Library of Congress)

‘Last Full Measure of Devotion’

More than 55,000 Connecticut men — between the ages of 15 and 50 — enlisted in the Union Army, but the oldest formed regiment that survived Gettysburg was the 5th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

The regiment formed at Camp Putnam in Hartford on July 22, 1861, under the command of Col. Orris S. Ferry (who later became Connecticut’s U.S. Senator from March 1867 – November 1875). The troops first experienced combat at the Battle of Front Royal, May 23, 1862, followed by major conflicts like the Second Battle of Bull Run and the Battle of Chancellorsville.

By summer 1863, the 5th regiment was commanded by Col. Warren Packer of Groton, who led 221 men from Littlestown, Pa., to Gettysburg. On July 1, the Union troops cleared Confederates occupying Wolf Hill; the following day, the 5th regiment formed a line on Culp’s Hill, but was ordered to support the 3rd Corps in the afternoon.

However, upon their return to Culp’s Hill, the position had been overtaken by Confederate troops — though they were not the only Connecticut regiment to discover the new reality.

The 20th regiment was formed on Sept. 8, 1862, in New Haven, more than a year after the 5th left Connecticut. Prior to Gettysburg, the troop’s first major engagement was at Chancellorsville. Under Lt. Col. William Wooster’s command, 321 men fought in skirmishes over the course of the three days at Gettysburg.

At daylight on July 3, both the 5th and 20th regiments attacked under the cover of artillery with the latter fighting five hours before regaining the hill. After the victory, both groups were sent to reinforce the 2nd Corps during Pickett’s Charge — a failed Confederate assault to break the Union’s center lines. Overall, the 5th regiment suffered relatively few casualties with two wounded and five missing men throughout the several days of battle, while five were killed, 22 wounded and 1 missing from the 20th.

Meanwhile, the least battle-tested group from Connecticut was the 2nd Independent Battery, Light Artillery, who organized in Bridgeport on Sept. 10, 1862. The 2nd artillery moved to positions around the Potomac and Virginia before being ordered to Gettysburg under the command of Capt. John William Sterling of Bridgeport, where the 106 men — armed with four 14-pounder James Rifles and two howitzer cannons — were positioned near present-day Hancock Avenue to repulse Pickett’s Charge. Like the 5th regiment, the 2nd artillery had minimal casualties with three wounded and two missing.

The Connecticut regiment that suffered one of the highest casualties — in terms of percentage — at Gettysburg was the 27th Infantry. Prior to the battle, the troop endured heavy losses at the Battle of Fredericksburg (110 casualties) and the Battle of Chancellorsville, where eight of the 10 companies were captured. Only 75 men were left to fight at Gettysburg. Commanded by Lt. Col. Henry Merwin, the 27th fought Confederates in the “Wheatfield” and into the woods beyond; however, Merwin was killed along with 38 other casualties during a charge. Ultimately, the regiment lost nearly 50 percent of its men. Three weeks after the battle, the regiment disbanded.

A print based on the painting ‘Hancock at Gettysburg’ by Thure de Thulstrup depicts Major Gen. Winfield S. Hancock riding along the Union lines during Pickett’s Charge. (Library of Congress)

From Barlow’s Hill to Pickett’s Charge

Like other Connecticut regiments, the 17th infantry — mustered in Bridgeport, Aug. 28, 1862 — engaged in the Battle of Chancellorsville in spring 1863, which proved to be a disaster for the Union Army. Yet the nearly 400 men in the regiment pressed on, arriving at Gettysburg on July 1 under the command of Lt. Col. Douglas Fowler. Fowler, however, would not live to see July 2, as the regiment fought on Barlow’s Knoll.

In his absence, Major Allen Brady took command of a line on East Cemetery Hill, repelling nighttime assaults by Harry T. Hays’ and Robert Hoke’s Brigades. Brady’s report describes a harrowing scene:

“When within 150 paces of us, we poured a destructive fire upon them, which thinned their ranks and checked their advance. We fired several volleys by battalion, after which they charged upon us. We had a hand-to-hand conflict with them, firmly held our ground, and drove them back.”

The regiment was eventually relieved by troops from Ohio, but remained exposed to sharpshooters throughout the night.

Meanwhile, the 14th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment organized in late August 1862. Less than a month later, the regiment fought in its first major action at the Battle of Antietam, the single bloodiest day in American history. Though declared a victory, the Union suffered greater losses than the Confederacy. The 14th regiment was not immune — with 20 killed, 98 wounded and 48 missing in action.

Then, in December, the 14th regiment was part of the assault on Marye’s Hill at the Battle of Fredericksburg where, once again, they endured numerous casualties (11 killed; 87 wounded; 22 missing). One soldier, Samuel Fiske, wrote, “My heart is sick and sad. Blood and wounds and death are before my eyes; of those who are my friends, comrades, brothers,” adding, “Another tremendous, terrible, murderous butchery of brave men.”

When the regiment arrived at Gettysburg on July 2, they had nearly 200 men remaining — a far cry from the initial thousand mustered in August 1862.

Nevertheless, the 14th was positioned on the Union’s center line. It was there the regiment “gained some degree of redemption,” according to author Matthew Warshauer. On July 3, the 14th regiment repulsed Pickett’s Charge and captured between five to six battle flags. Three men from the regiment — Elijah Bacon, Christopher Flynn and William Hincks — would later receive the Medal of Honor. Hincks’ citation is the most descriptive, stating:

During the highwater mark of Pickett’s charge on 3 July 1863 the colors of the 14th Tennessee Infantry C.S.A. were planted 50 yards in front of the center of Sgt. Maj. Hincks’ regiment. There were no Confederates standing near it but several were lying down around it. Upon a call for volunteers by Maj. Ellis, commanding, to capture this flag, this soldier and two others leaped the wall. One companion was instantly shot. Sgt. Maj. Hincks outran his remaining companion, running straight and swift for the colors amid a storm of shot. Swinging his saber over the prostrate Confederates and uttering a terrific yell, he seized the flag and hastily returned to his lines. The 14th Tenn. carried 12 battle honors on its flag. The devotion to duty shown by Sgt. Maj. Hincks gave encouragement to many of his comrades at a crucial moment of the battle.

Bacon and Flynn, meanwhile, captured the 16th North Carolina regiment and 52nd North Carolina Infantry flags, respectively. Flynn and Hincks would survive the war, while Bacon died during the Battle of the Wilderness, May 6, 1864.

Abraham Lincoln (center) gives the ‘Gettysburg Address’ to a crowd gathered for the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. (Library of Congress)

‘It Can Never Forget What They Did Here’

Gettysburg is a sweeping, epic battle that encompassed numerous skirmishes — and the Connecticut men performed their duty valiantly with many making the ultimate sacrifice. Even though the Union victory was a turning point that ultimately led to preserving the United States and the emancipation of slaves, the war endured for another two grueling years.

Today, Connecticut has more than 130 monuments to honor those who fought in the Civil War — including in my hometown of Milford. But how quickly we can forget what those brave men did at Gettysburg.

Ironically, Lincoln stated in his address that the “world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.” Yet his solemn, hopeful message tasked the living who gathered at Gettysburg on Nov. 19, 1863, and to subsequent generations of Americans, to not so much remember his words, but to devote themselves to the soldiers’ cause — that being the pursuit of a “new birth of freedom.”

At a time when political polarization feels dangerously strained, let’s remember our Connecticut men’s sacrifice to preserve the Union and the inalienable right that all men are created equal.

What neat history do you have in your town? Send it to yours truly and I may end up highlighting it in a future edition of ‘Do You Know CT?’. Please encourage others to follow and subscribe to our newsletters and podcast, ‘Y CT Matters.’

And a special thank you to the New England Civil War Museum in Vernon, Conn., for assistance. If you’re looking for more Civil War information, be sure to visit their website here.