The gimmicky gas tax cut adopted unanimously by the General Assembly in March, and extended to December 1 as part of the state budget, may be delivering less savings than promised.

Connecticut suspended its 25-cent-per-gallon wholesale tax on gasoline beginning April 1, forgoing roughly $30 million in monthly revenue in a bid to reduce prices at the pump. Governor Ned Lamont said the suspension would “provide some relief to consumers as they face rising prices,” while Republican Senate leader Kevin Kelly called the move a “no-brainer that will provide immediate relief.”

But comparing average regular gasoline prices in Connecticut with those in Massachusetts, it appears that the savings from the tax pause may not be what were anticipated. The Bay State provides an appropriate comparison because the state is similarly situated with respect to global supply patterns and officials in Boston decided against a similar move.

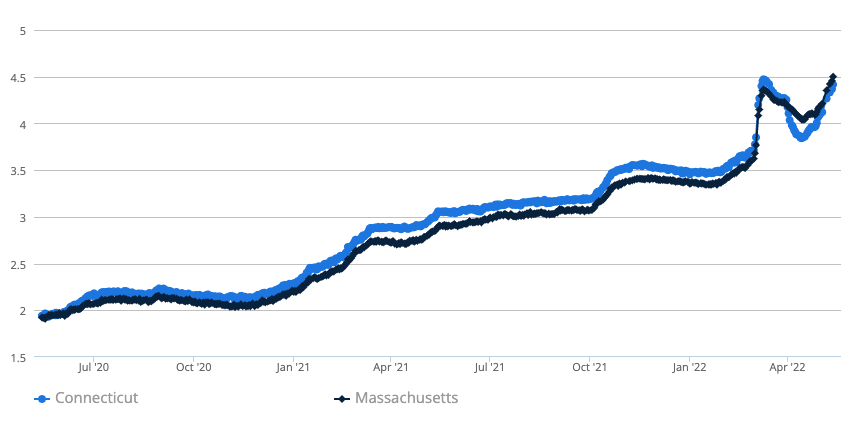

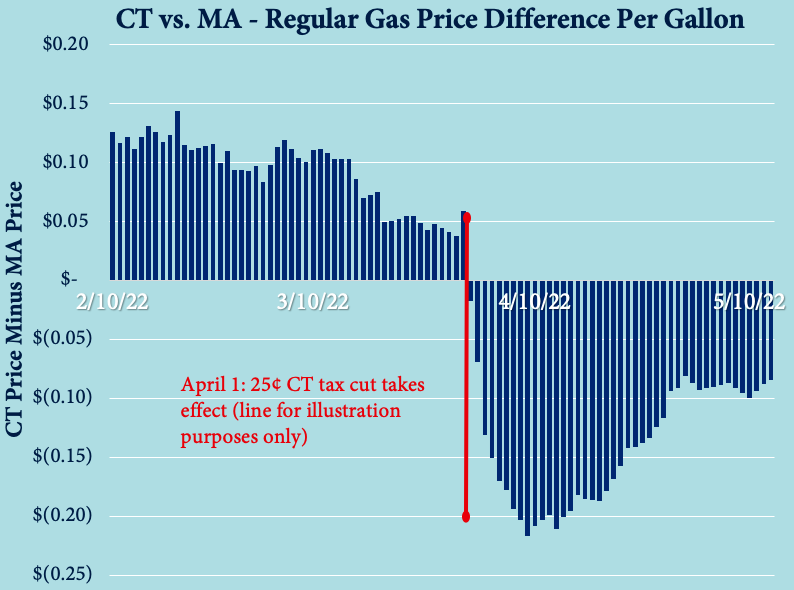

Data from the crowdsourced pricing website GasBuddy show the average price per gallon in Connecticut was typically 10 to 15 cents above the average paid in Massachusetts during the past year, with the difference averaging about 13 cents.

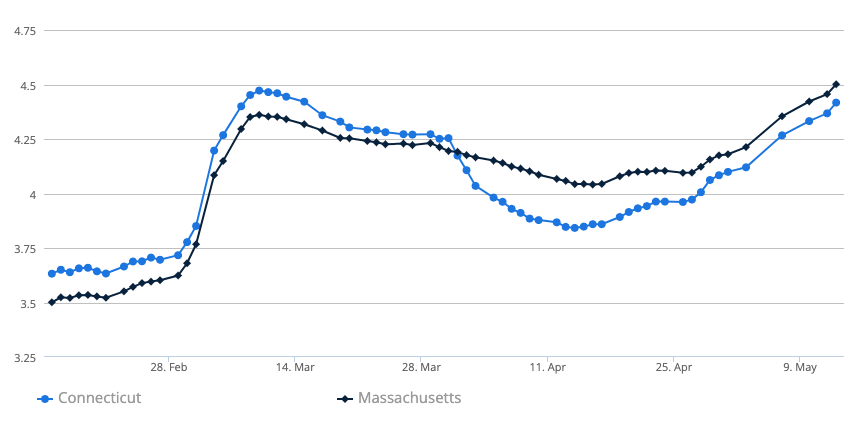

Prices in both states spiked in early March as crude oil prices surged, and were already trending down when Connecticut’s tax was suspended. Prices in Connecticut fell faster in late March, possibly in anticipation of the suspension, and came within 5 cents of the Massachusetts price.

Lawmakers required gas retailers to make a one-time price reduction to reflect the tax pause—which appears to have happened. Within a week of the April 1 tax cut, prices in Connecticut had fallen to 20 cents below Massachusetts as both states’ averages dropped and reached their recent minimums two weeks later. Connecticut bottomed out at $3.84 on April 14, and Massachusetts’ average hit $4.04 the same day.

But when prices began climbing in both states again in mid-April, Connecticut‘s average rose noticeably quicker. As of yesterday, May 13, prices averaged 11 percent above their April lows in Massachusetts but had climbed 15 percent in Connecticut.

Connecticut’s average price, over the course of a month, has gone from 20 cents below Massachusetts to 8 cents below Massachusetts prices. (See chart below).

Assuming conservatively that Connecticut’s “cut” average should be tracking around 15 cents below Massachusetts’ average (after tracking about 10 cents above), this means close to a quarter of the hoped-for savings have disappeared.

The Wrong Tax Cut

State officials were desperate to be seen doing something about high gas prices in the leadup to the November elections. But unable to travel back in time and boost domestic drilling or refining capacity, they reached for the only lever they could.

The fundamental challenge with using a tax cut to deliver price relief is that prices are opaque. Drivers don’t distinguish between what they’re paying to state government, or a European gas retailer, or a Canadian refinery, or a despotic Middle Eastern regime. The market was supporting a price, and absent any major change to supply or demand, the market would keep supporting a similar price (especially if higher prices had caused people within Connecticut to temporarily forgo driving).

What’s more, dropping Connecticut’s price by a quarter inevitably changed behaviors for interstate drivers and drew customers who otherwise would have fueled up in New York, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island.

The estimated $240 million state politicians are pilfering from the fragile Special Transportation Fund (STF) to buy themselves gas-related press releases and campaign ads could have made a modest dent in the $7 billion in outstanding transportation-related bonds, or avoided part of the $930 million the state was set to borrow in the next fiscal year for transportation. In both cases, the savings for taxpayers would have been larger if the state hadn’t cut the gas tax, since drivers would be avoiding future interest payments (when governmental borrowing costs are rising, no less).

Even if the state had found a way to steer the funds into additional or accelerated construction projects, bringing more roads into a state of good repair would have also reduced long-term costs by making future maintenance less costly.

It bears remarking that the tax move comes just two years after Governor Lamont and other officials pushed the return of tolls to Connecticut highways to shore up the STF, and months before the state phases in a highway use tax approved last year to help balance its books.

*Meghan Portfolio contributed to this analysis.*

NOTE: charts use day-before/day-after averages to estimate difference on days without average price data.