The U.S. Census Bureau population figures released last week raised eyebrows as Northeast states, including Connecticut, beat estimates.

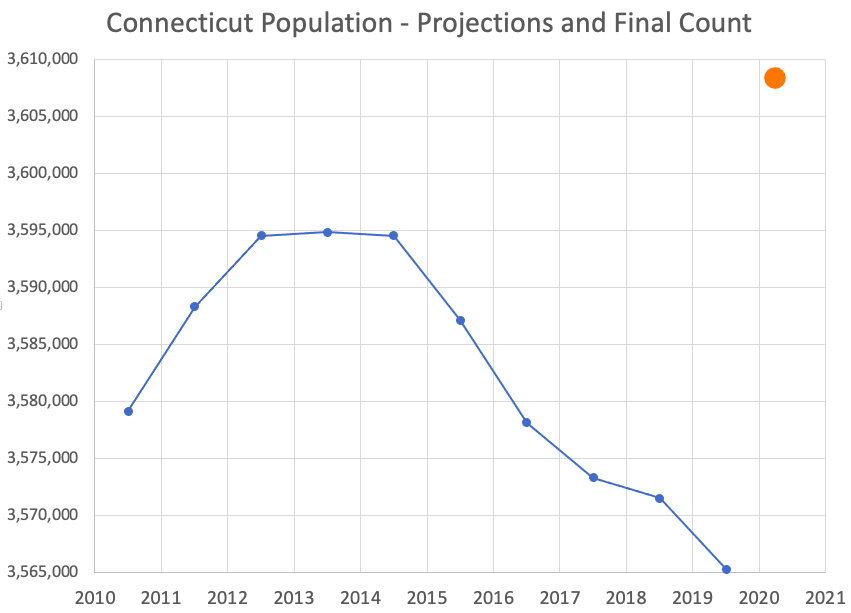

Census Bureau projections in recent years indicated Connecticut would end the decade with a small population loss, from 3.58 million to 3.56 million, after several years of declining births, increasing deaths, and more people leaving for other states than arriving. Instead, the 2020 census found, Connecticut’s population on April 1, 2020 was almost 3.61 million—a slight increase.

The federal census is an enormous and sophisticated undertaking. The final count is the result of the Bureau’s efforts to contact every household directly and then to extrapolate information about the ones they could not. But the divergence between the projections and the final count warrant close inspection in coming months because policymakers rely on both, and for Connecticut, one missed the mark in a big way.

Connecticut wasn’t the only state that beat forecasts in the 2020 census, but two states stood out: New York and New Jersey, where the 2020 census came in at least 4 percent above projections. As Lyman Stone, a demographer and adjunct fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, was first to point out, there appeared to be a correlation between a state bordering New York and its official 2020 count exceeding projections.

The Census Bureau hasn’t yet addressed this. But the Urban Institute in early 2020 raised concerns that the Census Bureau was using tools that were “insufficiently tested in a decennial census environment” that would “disproportionately improve the count of those who are already easiest to count.”

For Connecticut, the reported population growth on its face is good news, since it helped prevent the state from losing a U.S. House seat (as it did in 2000). But block-level census data will be used later this year to draw the state House of Representatives and state Senate district lines for the 2022 election. And if figures are in any way skewed by some unseen factor (either in census data collection or in modeling) that’s more pronounced closer to New York, it could lead to state legislative maps that unduly favor areas closer to the border.

On the other hand, it’s possible the 2020 census figure is closer to Connecticut’s actual population than the intra-decade projections. The tools behind those projections play a big role in public policy matters ranging from housing to unemployment statistics—and it would mean that Connecticut policymakers have for years been getting inaccurate reads on important issues.

And given the intense discussions around the cost and availability of housing, and the state’s seemingly stalled economic recovery, a clear read of the facts on the ground is crucial.