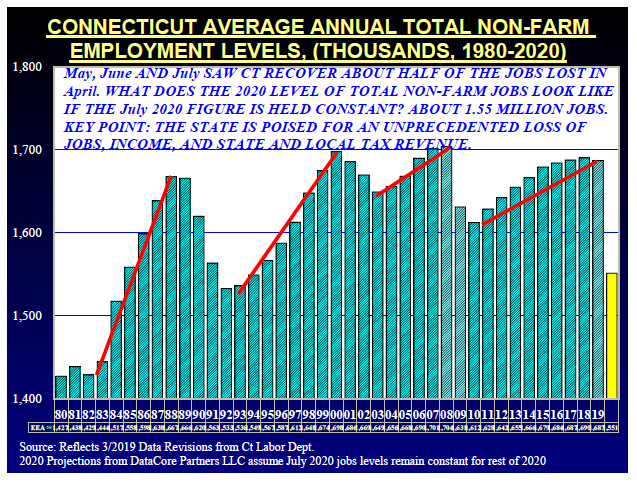

With only a few months left in the year, it is almost certain that 2020 will mark the largest annual job loss in Connecticut’s history going back to 1960 due to the pandemic and, according to research, it is likely Connecticut will have a long and slow employment recovery.

Connecticut’s unemployment rate currently stands at 10.2 percent, although the Department of Labor has warned the figure could be higher due to difficulties in data collection.

According to data compiled by Donald Klepper-Smith, chief economist for DataCore Partners, LLC and former economic advisor to Gov. M. Jodi Rell, Connecticut’s average annual job loss for 2020 so far stands at roughly 8 percent.

Prior to this year, 2009 was the second largest annual job loss due to the 2008 recession, which saw employment drop by 4.27 percent.

Connecticut, unlike its neighbors and most of the rest of the country, never fully regained the jobs lost during the last recession. Massachusetts, for instance, recovered more than 370 percent of the jobs lost in 2008 and 2009, while Connecticut regained only 86 percent, the lowest rate in New England.

Meanwhile Connecticut’s annual job growth never rose over 1 percent between 2011 and 2020, a time when the nation, as a whole, experienced long-term economic growth.

But what may be more foreboding is that Connecticut’s job recovery has been slowly decreasing after each downturn, something Klepper-Smith attributes to a structural change in employment, including substituting technology for human labor, use of temporary workers, the costs of doing business and globalization.

“I think the growth rate going forward will be substantially less,” Klepper-Smith said. “We’re not going back to prior peaks anytime soon.”

To put it a different way, Connecticut’s job recovery curve since 1980 has flattened, meaning that if the trend continues recovery will take longer. “It shows that we’re gaining jobs at a lesser and lesser rate,” Klepper-Smith said.

Even since 2011, when Connecticut saw its first uptick in average annual job growth, the following years show less and less growth until finally resulting in annual job loss in 2019 – and that was before the pandemic, which saw 269,000 jobs lost in roughly one month.

Although the state is seeing increased job numbers since the height of the shutdown, particularly in the leisure and hospitality sector of the economy, those are only gains relative to the largest job loss in 60 years.

And despite revenue to the state coming in higher than previously predicted, thanks in large part to federal grants, the long-term effects for Connecticut have not yet been felt. State Comptroller Kevin Lembo is forecasting a 6 percent drop in revenue for the 2021 fiscal year.

“The state is poised for an unprecedented loss of jobs, income, and state and local tax revenue,” Klepper-Smith said.

Connecticut has roughly $3 billion in its rainy day fund, enough to weather the fiscal storm for the next year, which is projected to run a $2 billion deficit, but the following years will present a challenge for lawmakers.

Large deficits in the past were met with tax increases in 2009, 2011 and 2015 and labor negotiations between the governors and SEBAC in 2009, 2011 and 2017.

But the changes never put Connecticut on a steady path toward fiscal stability. Expenses related to fixed costs continued to rise faster and more steadily than revenue.

Although the pandemic hit the leisure and hospitality sector the hardest, every job sector in the state saw a year over year loss, wiping out ten years of Connecticut job recovery in just a couple months.

And if the historical trend holds, Connecticut’s job recovery this time may be slower than previous economic recoveries.

“The implications of this data are pretty profound,” Klepper-Smith said.