Gov. Dannel Malloy’s budget chief offered a roadmap for Governor elect Ned Lamont’s new administration, which included eliminating scheduled tax cuts, cutting back Medicaid, reducing state aid to some municipalities, and transferring some teacher pension costs onto towns and cities.

Office of Policy and Management Secretary Ben Barnes wrote “These options would be difficult, and would involve real sacrifice by various constituencies; the Malloy administration did not repeatedly put hard choices like these on the table without significant forethought, knowing that many in the legislature may have preferred to take a different approach including more revenue.”

Barnes also wrote the state could potentially find new revenue through marijuana legalization, sports gambling legalization and implementing tolls.

The budget suggestions repeat some prior Malloy administration attempts to right Connecticut’s fiscal problems – namely transferring teacher pension costs onto towns and cities and implementing tolls.

Barnes proposes transferring the normal cost of teacher pensions onto municipalities, while the state would continue to pay the unfunded liabilities.

The normal cost of teacher pensions is the savings for current teachers. As of 2016 that cost was $180.1 million, but the numbers vary year-to-year. That will mean added costs for cities and towns and could put some municipalities which are already facing difficulties in a tough spot.

Malloy had previously suggested transferring one-third of the cost of teacher pensions onto municipalities, which met with stiff resistance from municipal organizations like the Connecticut Conference of Municipalities who argued the state was responsible for teacher pensions and the added costs would drive up property taxes.

Barnes wrote “The Teachers’ Retirement System is a major piece of aid to local governments, and is regressive in nature because more affluent districts pay larger salaries and employ more teachers, driving a higher state pension subsidy, while poorer communities employ fewer, less well paid teachers. There are many variations of this idea that would address ability to pay concerns.”

Malloy had previously reduced or held flat education cost sharing grants for municipalities, particularly during the 2017 budget battle. State education funding is the largest non-fixed cost for the state.

The proposals also call for reducing state aid to municipalities through the state’s Payment in Lieu of Taxes program.

The Malloy administration also recommended reducing Medicaid payment rates to “certain providers” and reducing eligibility levels for adult Medicaid recipients from 155 percent of the poverty level to 138 percent. Medicaid is the largest fixed cost in the state.

reducing eligibility levels for adult Medicaid recipients from 155 percent of the poverty level to 138 percent. Medicaid is the largest fixed cost in the state.

Other proposals included reducing the number of state employees through attrition and restructuring employee benefits to save 5 percent of active employee health benefits costs.

While the proposals are suggestions for the incoming administration, the continuing push for reductions in state aid to municipalities, Medicaid, and the shifting of part of the teacher pension costs onto towns could jangle some nerves.

Governor elect Ned Lamont ran on a platform of reducing the property tax for state residents, which could be difficult if education cost sharing grants are reduced and municipalities have to support teacher pensions.

While the state faces a two-year budgetary shortfall of $4.4 billion, income tax revenue projections increased by $880 million, reducing the fiscal gap.

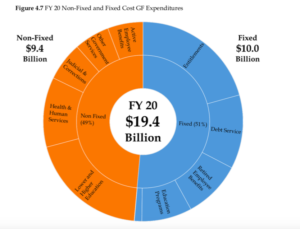

Fixed costs – particularly debt service and pension costs for state employees and teachers – are projected to increase $620 million next year, according the Office of Fiscal Analysis, and another $1.1 billion the following two years.

“I strongly urge you to consider a budget strategy that focuses not on one-time gimmicks, but rather recurring revenue and cost savings,” Barnes wrote.