A withering assessment of Connecticut’s economic and fiscal problems was used by Pioneer Institute — a think-tank based in Boston — as an example of why Massachusetts should not raise taxes on high-income earners.

Pioneer Institute’s study “Back to Taxachusetts” tracks ten years of Connecticut data from 2008 to 2017 and is rife with sections entitled “Corporate exodus,” “Stagnant economy,” and “Voting with their feet,” to show Connecticut’s tax policies have left the state failing, whereas Massachusetts has become an economic powerhouse.

“Connecticut provides a real-world, sobering example of how a seemingly attractive tax-the-rich scheme can backfire badly on a state, turning rosy projections of revenue gains to real-life losses, and damaging business confidence in the process,” wrote Gregory W. Sullivan, research director for Pioneer Institute.

The study was authored in response to a “coalition of labor unions, community groups, and social advocacy organizations,” trying impose a 4 percent tax surcharge on individuals in Massachusetts earning over $1 million per year through a “Fair Share Amendment” to the state constitution. The amendment was placed on the voter ballot, but was challenged in court.

The surcharge would drive Massachusetts’ tax rate from a flat 5.1 percent to 9.1 percent for those high-income earners.

Although Massachusetts earned the moniker “Taxachusetts” in past years, Connecticut’s income taxes for individuals making over $50,000 per year are higher than its neighbor-to-the-north.

Connecticut’s embrace of an aggressive tax policy to pay for ballooning government debt — including a sharp hike in the rate corporations pay — has been a major driver in the loss of a number of bedrock employers. And higher corporate tax rates, combined with hikes in the income tax and especially the estate tax, also appear to be a factor driving away a growing number of the state’s wealthiest residents.

The study notes Connecticut has increased its income tax on top earners 77 percent since 1991, raising the rate from 4.5 percent to 6.99 percent.

“Behind the increases have been escalating public employee pension obligations and health benefits, and payments on Connecticut’s large debt load, which has now reached into the tens of billions,” the study says.

Massachusetts, on the other hand, lowered its tax rate from a high of 6.25 percent in 1991 to 5.1 percent in 2017.

Gov. Dannel Malloy raised taxes twice in 2011 and 2015, but the additional state revenue from those increases has only paid for increasing pension costs, according to Office of Policy and Management Secretary Benjamin Barnes.

Despite those tax increases, Connecticut continues to face multi-billion budget deficits.

Lawmakers barely managed to tackle a $5.3 billion deficit in 2017 and potentially face a $4.6 billion deficit for the next biennium.

The SEBAC concessions agreement with state employee unions locked in salary raises and layoff protections for the state’s workforce for the next four years, essentially leaving lawmakers with few options in the upcoming budget battle and raising the specter of future tax increases to make up the difference.

The SEBAC deal also locked in pensions and benefits until 2027, making reforms to the system in order save money difficult without further concessions by state labor leaders.

Combined with a slew of other tax increases and fees on corporations and businesses, Connecticut’s tax climate has led to its downfall, according to Pioneer, and they supply the data to back it up.

- Connecticut is ranked 2nd in the country for state and local tax burden by the Tax Foundation, whereas Massachusetts ranks 12th.

- Private sector jobs in Connecticut since 2008 are down 1.9 percent, compared with Massachusetts, which is up 9.4 percent.

- Connecticut has only recovered 72 percent of jobs since the 2008 recessions, compared to 354 percent in Massachusetts — although Connecticut’s figure was recently revised to 82 percent.

- Connecticut had the third lowest private sector wage increase in the country, and the lowest home value growth of all 50 states.

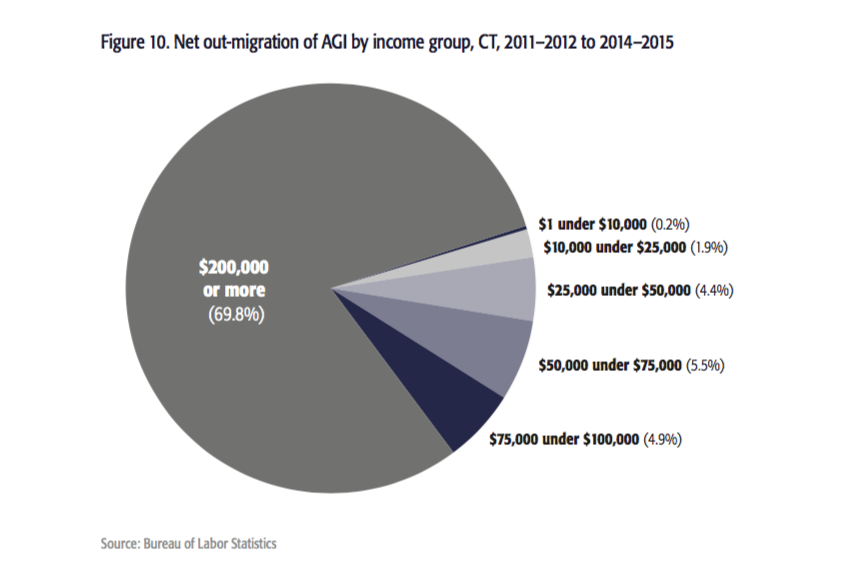

- Connecticut saw an outmigration of individuals making over $200,000 per year, which coincided with the 2011 and 2015 tax increases. High-income earners made up nearly 70 percent of the people leaving Connecticut during those times, according to the study.

The study also points out the Connecticut has seen the slowest growth in the number of millionaires in the state. The number of individuals with incomes over $1 million increased only 27 percent in Connecticut, whereas nationally the average was 55 percent.

Connecticut has lost investment firms and billionaires like Paul Tudor Jones and Edward Lampert to Florida, who take with them tens of millions in income tax revenue.

Barry Sternlicht will move his $55 billion real estate fund, Starwood Capital, to Florida by 2021, according to a report by Bloomberg News.

Changing fortunes for Connecticut’s high-income earners can have big ripple effects for Connecticut tax revenues. The 2017 budget deficit increased more than $1 billion when tax returns for investment earnings plummeted.

Conversely, gains on Wall Street bailed Connecticut out of deficits for 2018 and 2019, although the increase was likely a one time occurrence, according to Comptroller Kevin Lembo and Gov. Dannel Malloy.

Similar to the Massachusetts legislation discussed in the study, labor coalitions in Connecticut have called for increased taxes on the wealthy, including a 19 percent surcharge on financial services, which received a public hearing in 2017.

President of the Connecticut Hedge Fund Association Bruce McGuire told lawmakers the tax would drive more investors out of state.

Connecticut did make one tax policy change meant to keep wealthy residents from fleeing to other states. Lawmakers passed a bill in 2017 raising Connecticut’s estate tax threshold to meet federal guidelines.

However, Connecticut’s estate tax law will have to play catch-up to the federal government, which is also raising the federal estate tax exemption amount through 2025.

The “Fair Share Amendment” was struck from the state ballot by the Supreme Judicial Court on Monday, sending the tax issue back to the legislature.

There is also a push by business organizations in Massachusetts to lower the state’s sales tax from 6.25 percent to 5 percent.

DrHunterSThompson

June 20, 2018 @ 2:11 pm

While the study (or summary of the study) tells us quite a bit of what we know it doesn’t seem to give us the “why” or any hint of solution.

Texation is rarely the reason for any move, personal or corporate, but it certainly can be the final straw.

I’m very skeptical of this report. It seems as though it has an agenda. And that is not good for any study or research group.

Tom

June 24, 2018 @ 11:53 am

I love those high taxes in Connecticut, I sell new homes in South Carolina and have a growing client list moving here from TaxCon.

They don’t mind paying their “Fair Share” , but those rates are tantamount to theft, so they left. It’s just that simple.

Jim

August 16, 2018 @ 1:05 am

To the fellow who said “taxation is rarely the reason for any move…”, on what data do you base this? I ask because it simply seems to defy common sense!

Mark A. Bibbins

February 22, 2021 @ 7:03 am

I agree with you.

P Kennedy-Sztyblewski

January 5, 2019 @ 10:36 am

I know all this; as both a M.I.T and Yale graduate, I’ve found my life in Connecticut to have been cheaper over the years than whenever I try to come back to Massachusetts. Sales tax is lower, rents have been more reasonable (now granted I’ll tend to gravitate back to New Haven and not the nicer parts of the state, and I know where to get the cheaper things in New Haven vs. the nicer things the stereotypical Yalie should have) and I’ve never quite wound up on Connecticut’s streets as the domestic violence system there has never let me down as has Massachusetts’ recently. I figured the difference between the two states was income tax, as I’ve never had an income over $35,000 a year since graduating Yale in 1996 with my Master’s. Connecticut even has, as of recently, more social programs to keep domestic violence victims off the streets whereas Massachusetts seems to keep shutting theirs down. On that front I think it strives to NOT be like its two neighbours, Massachusetts and New York. It’s not felt deluged with “the whole world wanting to come to America wants to come here” at least there’s no sentiment to that effect as of the last time I tried to live in New Haven (2016).