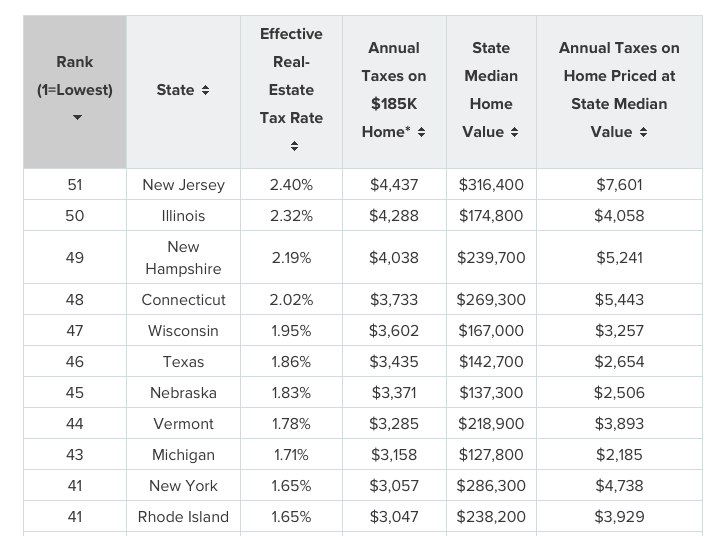

An annual study by WalletHub ranked Connecticut 48th among the states for its real estate property tax burden and 43rd for its vehicle property tax costs.

In total, the 2018 study noted the median real estate property tax cost for Connecticut homeowners is $5,443 per year, while the median property tax for a vehicle is $603.

Only New Hampshire, Illinois and New Jersey had higher property taxes than Connecticut. Overall, the study found that “blue states,” which are largely clustered in the Northeast United States, tend to have higher property taxes.

“We all pay property taxes,” the report says, “whether directly or indirectly, as they impact the rent we pay as well as the finances of state and local governments.”

In Connecticut, however, the state finances may cause some big problems for local finances in the coming years, and that could drive up property taxes in a state where residents already face a hefty burden.

Connecticut is projected to face a $4.6 billion deficit during the next biennium and lawmakers will find themselves trapped between a rock and a hard place when it comes to either cutting costs or raising taxes.

The 2017 SEBAC concessions deal negotiated between Gov. Dannel Malloy and state employee union leaders established layoff protections until 2022, lump sum bonuses equaling $104 million and 7 percent raises in 2019 and 2020.

The bonuses and raises combined with layoff protections for all of Connecticut’s unionized state employees means lawmakers will face increased costs in the upcoming years.

To make matters worse, the state income tax revenue — Connecticut’s largest source of income — has stalled in recent years and even declined in some instances, leaving growing gaps in the state budget.

This leaves lawmakers facing the unpalatable options of either raising taxes again or cutting municipal aid, which is the state’s largest expense after its debt and pension obligations.

Local leaders already faced a challenging start to the 2018 fiscal year when the governor and legislature failed to reach a budget agreement, forcing Malloy to run the state by executive order until a budget was passed in November.

Malloy moved to eliminate education funding to 85 towns across Connecticut and severely cut funding to another 54 municipalities.

The last minute bipartisan budget deal restored most of the municipal education funding, but towns faced cuts once again when Malloy slashed $91 million in education aid as part of the budget agreement, which directed him to find $182 million in savings.

Municipalities, which are also facing rising education costs due to collectively bargained salary increases and insurance costs, may be faced with further cuts in the future which will likely lead to higher property taxes in order to balance their budgets.

If, on the other hand, lawmakers choose to raise state taxes — an idea pushed by government union leaders — it could lead to more outmigration and loss of wealth from Connecticut, further exasperating the state’s income tax revenue problems.

Connecticut’s tax revenue has continually fallen short of expectations following the last two major tax increases of 2011 and 2015.

Connecticut’s motor vehicle property tax has also been at the forefront of debate. The state tried to cap the mill rate for vehicle taxes at 37 mills and then reimburse the difference to municipalities which charged higher rates.

However, due to the state’s continual budget problems, the cap was raised to 39 mills so the state wouldn’t have to reimburse towns as much money. The rate is set to rise again to 45 mills this year for the same reason.

New York ranked 41 for real estate property taxes and Massachusetts was ranked 34 by the WalletHub study. New York does not have a motor vehicle property tax and Massachusetts’ vehicle property tax is capped at 25 mills.