Connecticut classrooms and teachers could receive a big boost if not for the massive pension debt in the state teacher pension system, according to a study entitled The Pension Pac-Man: How Pension Debt Eats Away at Teacher Salaries.

Connecticut pays $14,374 per teacher per year toward the teacher pension debt, money that could be used to increase teacher salaries or improve children’s education.

“It can be somewhat abstract for teachers to think about pension debt and how it affects them, but it means that their employer and their state have less money to spend on education generally or teachers more specifically,” study author Chad Aldeman wrote. “Regardless of other spending priorities, states, school districts, and individual schools must squeeze other areas of their budgets to pay for rising pension payments.”

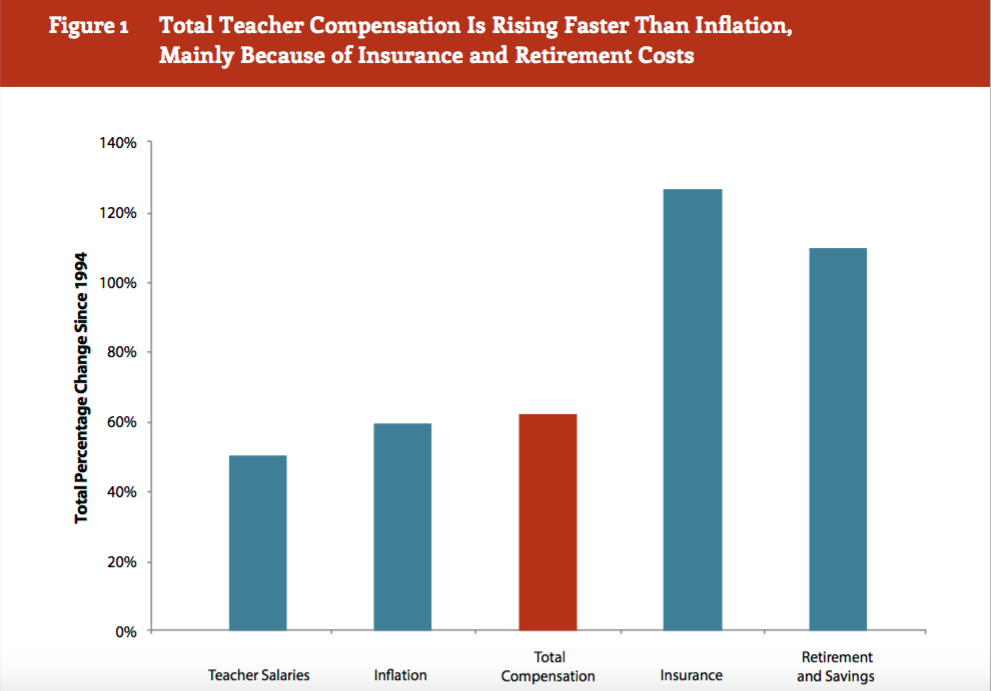

Compensation for teachers is rising faster than inflation, according to the study, but that doesn’t mean teacher salaries are growing at a commensurate pace. Instead, retirement and insurance costs — which make up total teacher compensation — are growing extremely fast, while salaries have not risen as quickly.

A large portion of those costs are teacher pension liabilities. In 2016 Connecticut paid nearly $1.2 billion toward teacher pensions. Of that figure, $1 billion went toward unfunded liabilities.

To put that in perspective, during the 2016-2017 school year, Connecticut’s Education Cost Sharing payments to every municipality in the state totaled $2 billion.

The cost of those unfunded liabilities is expected to grow from $1.2 billion per year to possibly $6 billion per year by 2032.

“If states continue to preserve the existing retirement systems at any cost, teachers will see rising pension costs eat further and further into their take-home pay,” the study said.

That prediction has already started to come true. As part of the 2017 budget agreement, teachers had to increase their pension contribution from 6 to 7 percent, equaling $38 million per year. The increase will not help the pension system, however, because the state will decrease its contribution in an effort to save money.

Connecticut teachers are already receive an average pay of $77,000 per year and have the one of the highest average pensions in the country at $59,000 per year, according to the Office of Fiscal Analysis.

But past studies have shown that a large number of Connecticut teachers miss out on those benefits.

A study by Education Next found that only 34 percent of Connecticut teachers actually stay in the profession long enough to become vested in the pension system and see a return on their investment.

Education Next recommended states switch teachers to 401(k) or hybrid plans to better ensure teachers keep what they earn in savings. The state of Michigan recently switched new teachers to 401(k) style retirement plans in order to deal with a $29 billion shortfall in its teacher pension system.

Unlike state employees, teacher pensions are set in statute and can be changed legislatively. Although such changes are politically difficult, they may become unavoidable as the cost of the unfunded pension liabilities continues to grow.

“Teachers in Connecticut, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, and West Virginia are currently losing out on compensation equivalent to 20 percent of their salaries just to pay down pension debt,” Aldeman wrote.