Connecticut’s bond commission just approved another $1 billion in general obligation bonds to be issued for schools, capital projects and tax credits to businesses, but beginning in 2018 the state will begin to issue a new type of bond.

Included in the bipartisan budget package was a provision to issue new revenue bonds tied directly to Connecticut’s income tax, which the Treasurer’s office described as “stable and strong.”

According to the proposed legislation from the Office of the State Treasurer, “this structure capitalizes on the State’s high wealth levels and insulates the bonds from budget and pension concerns, thereby earning higher credit ratings and lowering borrowing costs.”

“Experts say that this new type of bond better insulates the bond holder because it is backed by a specific revenue source,” David Barrett, spokesman for the State Treasurer’s Office, said in an email.

General Obligation bonds allow the state to pay its debt service through any means – or revenue source – available, but the new revenue bonds will be paid for exclusively out of Connecticut’s income tax stream.

Connecticut experienced a series of credit downgrades throughout 2017, which will raise borrowing costs in the future. Chief among rating agencies’ concerns was the growth of Connecticut’s fixed costs such as unfunded pension liabilities and, of course, debt costs.

S&P Global Ratings warned of a negative outlook on Connecticut’s most recent round of bonding. “Above-average debt, high unfunded pension liabilities, and large unfunded other post-employment benefit liabilities … create what we believe are significant and growing fixed-cost pressures that restrain Connecticut’s budgetary flexibility,” the ratings agency wrote.

Adding to the state’s debt pressures, Gov. Dannel Malloy issued a warning last week that Connecticut’s Special Transportation Fund faces insolvency due to its ever-growing debt burden. The state will not be able to issue transportation bonds for new projects until the STF is balanced.

One of the potential solutions offered by the Office of Policy and Management is to issue General Obligation bonds for transportation projects, “to offset the reduced bonding capacity in the STF.”

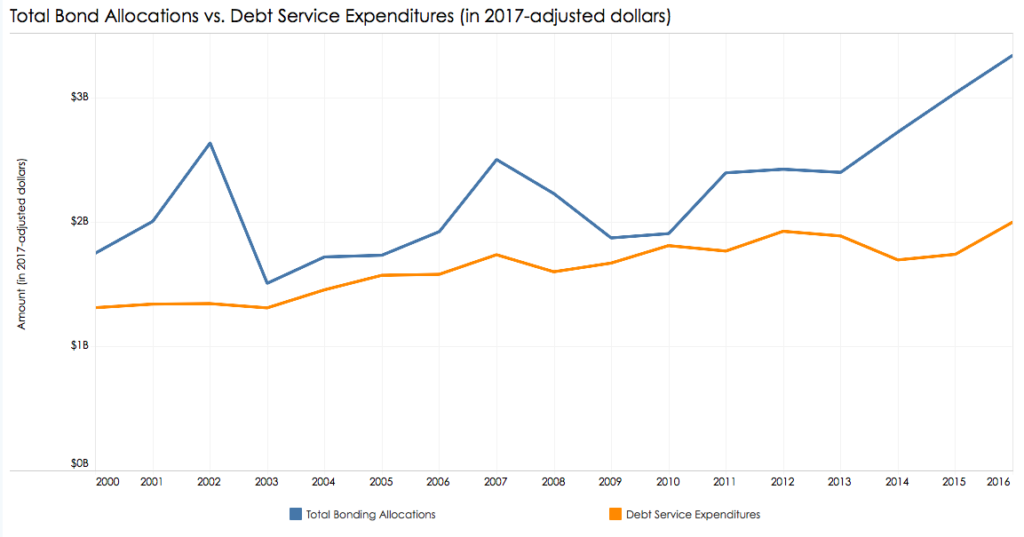

Payments for Connecticut’s debt is one of the fast-growing “fixed costs” which have been driving up government expenses. Connecticut’s bonding has nearly doubled since 2000, and debt service has grown from 1.3 billion to $2 billion during that same time, according to CTStateFinance.org.

Connecticut is not the first to try to improve its borrowing situation by tying bonds to a specific revenue source. New York began issuing personal income tax bonds in 2001 as a way to save money. The PIT bonds – as they are referred to – achieved a better credit rating than the state of New York’s general obligation bonds.

New York also issues bonds tied to the state’s sales tax, as well.

According the Treasurer’s office, Connecticut’s income tax bonds will have a better credit rating and lower borrowing costs. The savings will be transferred into the state’s rainy day fund to help with future budget issues.

Although Nappier described the state income tax as “stable and strong,” State Comptroller Kevin Lembo described the tax as “volatile” in his report on the budget reserve fund.

“Connecticut’s high concentrations of individual wealth and significant number of corporate headquarters result in large fluctuations in revenue as economic conditions change. Revenue fluctuations result in significant revenue shortfalls when the economy is under-performing, requiring cuts in programs, reductions in aid to cities and towns, tax increases or all of the above,” he wrote.

Lembo’s report advocated for increasing the cap on the rainy day fund from 10 to 15 percent of the budget in order to better meet budget needs when revenues fall short.

Income tax bond-holders will have will have the first cut of Connecticut’s income tax revenue, but that revenue has historically come up short, leaving state lawmakers scrambling for last-minute fixes and raiding the rainy day fund to make ends meet. The budget reserve fund was almost emptied in 2017 when income tax revenues came in lower than projected and left a $390 million deficit.

The 2017 budget crisis was made billions worse when the state failed to meet its revenue goals, and this year the Office of Fiscal Analysis and the Office of Policy and Management are predicting further declines in income tax revenue, leading to a $207 million deficit.

State projections indicate Connecticut will likely face a $4.6 billion deficit the next budget cycle at precisely the same time state employees are scheduled to receive raises.

However, if any problem exists with the new bond itself, but rather with what Connecticut’s need to switch to an income tax bond represents — namely, that the full faith and credit of the State of Connecticut is no longer enough for bond-holders.

The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board labelled the new bond as a “debt trick” and claimed that bond-holders would be less secure in the event of a default because there would be “competing creditor claims.”

Sen. L. Scott Frantz, R-Greenwich, and chairman of the Finance, Revenue and Bonding Committee told Bond Buyer Magazine that the new bond “sends out a message that Connecticut is becoming more desperate to shore up its fiscal foundation, the state needs to do everything it can to reduce expenses and manage through its perpetual short-term cash crunch.”

Gov. Dannel Malloy – whose administration has overseen a steep increase in bonding – coined the phrase “new economic reality” to signify Connecticut’s stalled growth and growing expenses, which has led to a perpetual state of fiscal crisis and the need for cost-cutting measures.

The personal income tax bonds may be a new type of bond for the new economic reality – not something lawmakers necessarily want to do, but are left little choice due to Connecticut’s poor fiscal and economic position.

frederick haeseler

November 17, 2018 @ 10:05 am

I came across this helpful article almost a year after its publication when our debt crisis has grown even deeper. I would like to pose the following question in the event readers might have knowledge to share. According to information on the www Rhode Island has been able to work its way out of a debt crisis similar to that of CT under the leadership of a former CEO and present governor, Gina Raimondo.RI is similar to CT–a small coastal New England state with a high pension burden and a contraction in industry. In fact CT should be in better shape owing to its strong educational and health care presence. Is it true that Gov Raimonda fixed serious deficit problems and if so how did she do it?