On May 9, following a 14-hour debate in the Connecticut House of Representatives, state Rep. Robyn Porter, D-New Haven, delivered an impassioned final speech in support of raising the state’s minimum wage to $15 per hour.

She had been on her feet through the night fielding questions from Republicans, who used the opportunity to show their grit in the face of an overwhelming Democratic majority. Porter only took occasional breaks, letting a fellow Democrat step in.

She had been fighting for the minimum wage increase for years, and this year it would finally pass.

Porter, a former employee of the Communications Workers of America, thanked her union brothers and sisters on the House floor as House Speaker Joe Aresimowicz, an employee of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Council 4, readied to call the vote.

Everyone – both legislators and those watching at the Capitol – already knew how the vote would turn out. Raising Connecticut’s minimum wage to $15 per hour had been a sought-after goal for many Democrats since the state’s minimum wage hit $10.10 per hour in 2017. A bill to raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour was voted out of the Labor and Public Employees Committee multiple times only to die later in the session.

Laphonza Butler, President of SEIU ULTCW, the United Long Term Care Workers’ Union joins workers demanding the Los Angeles City Council to vote to raise the minimum wage in 2015.

Now, with solid Democratic majorities in both the House and Senate, as well as a new Democratic governor who said he would support the measure, Connecticut was poised to become the sixth state to pass a $15 minimum wage.

But the Fight for $15 in Connecticut wasn’t just pushed by lawmakers: it was a primary goal of public-sector union leaders who repeatedly pushed the bill forward in the Capitol and lobbied legislators to pass it.

State union leaders advocated the increase, but it was part of a national movement spurred by national labor unions out of Washington, D.C. They recognized they could be more effective by pushing minimum wage increases at the state rather than the federal level.

The Fight for $15 began in 2012 when the Service Employees International Union attempted to organize fast food workers in New York City. According to one organizer, the $15 goal was more a matter of coming up with a catchy slogan and finding the right number rather than a research-backed need.

Kendall Fells, an SEIU union organizer who helped kick-start the movement in New York City, said $15 was settled on by fast-food workers because $10 was too low and $20 was too high.

The coordinated, $90 million Fight for $15 campaign quickly spread to other cities and eventually states, including California, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Massachusetts and finally Connecticut.

No sooner did Connecticut’s minimum wage hit $10.10 per hour – an increase signed into law by Gov. Dannel Malloy in 2014 – than bills to increase the wage to $15 started getting passed out of the Labor and Public Employees Committee with the full backing of Connecticut Democrats, labor union leaders and a host of union-backed organizations such as the Working Families Party, the Connecticut Citizen Action Group and Connecticut Voices for Children.

The increase was opposed by business association leaders and organizations, who argued the increase was too much, too fast, and would ultimately cost jobs and raise the cost of goods and services in the state. Connecticut employers were facing a 72.4% increase in the state’s minimum wage over 10 years.

Forum Plastics – a medical manufacturing company based in the beleaguered city of Waterbury – issued a warning telling lawmakers they would be forced to move out of state if the $15 minimum wage was passed.

The $15 minimum wage was hardly an economic panacea elsewhere: some workers earned more money while others lost their jobs or faced reduced hours and benefits. That likely would not bode well for a state such as Connecticut, which continues to face economic stagnation since the 2008 recession. The state’s job growth and personal income growth ranked among the lowest in the nation and Connecticut ranked third year-over-year for residents moving to other states, many in search of work.

But the Fight for $15 was not a fight for an improved economy or for more jobs. Rather it was a political fight meant to boost union power through organizing, rallying, and bending state and local governments to their will, regardless of the outcome.

While SEIU organized the movement nationally, AFSCME International, the American Federation for Teachers and the AFL-CIO all signed on to Fight for $15 through resolutions passed at their international conventions.

In 2014, Executive Director of AFSCME Council 4 in Connecticut, Sal Luciano, proposed and passed a resolution at AFSCME’s 2014 convention in Chicago to pressure the Obama administration to increase the federal minimum wage to $10.10 per hour, matching Connecticut’s increase.

That never happened. By 2016, AFSCME adopted a new resolution to support the Fight for $15 at all government levels and to urge “all candidates on the local, state and federal level to make support for a $15 per hour minimum wage a prominent part of their campaign platform, and to work diligently to pass legislation once elected to office.”

The Fight for $15 stalled in the Connecticut legislature for two years until a sweeping victory by Democrats in the 2018 elections secured their majorities in the House and Senate.

The electoral sweep was largely unexpected. Out-going governor Malloy was deeply unpopular, the state was stuck in an economic malaise and trailed the rest of the country in job growth, taxes had been raised significantly in 2011 and 2015, and the specter of unfunded pension and retirement liabilities for both state employees and teachers threatened to continue the cycle of budget deficits and tax increases.

In 2018, the Connecticut Senate was tied between Republicans and Democrats and there was only a slim Democratic majority in the House. Gubernatorial candidate Ned Lamont faced a tough fight to emerge from Malloy’s shadow.

Fear of what a Republican governor or Senate victory could mean for their legislative agenda mobilized Connecticut’s public-sector unions. They poured money into the elections.

SEIU 1199 alone spent over $1 million in independent expenditures – money spent to promote a candidate without coordinating with the candidate’s campaign – to elect Lamont governor and secure Senate victories for Mary Abrams, D-Meriden, and former union organizer Julie Kushner, D-Danbury.

AFSCME Council 4 also spent on Lamont, Abrams and Kushner, although far less than SEIU.

AFSCME Council 4 also ponied up money to help elect former-state Reps. Matthew Lesser, D-Middletown, and James Maroney, D-Milford, to the Senate and used independent expenditures to keep incumbents in office including Sens. Steve Cassano, D-Manchester, Mae Flexer, D-Killingly, and Christine Cohen, D-Guilford.

Although the unions didn’t spend reportable money on his election, they held rallies with Attorney General candidate William Tong. He eventually won his election and went on to offer his support for so-called “captive audience” legislation, which had been previously defeated in the legislature because it ran afoul of national labor law.

But union money to support and oppose candidates in Connecticut’s 2018 elections didn’t just come from unions inside Connecticut.

Both marching orders and money flowed from the international union affiliates in Washington, D.C., down to Connecticut, as it had in previous years.

The Fight for $15 is just one highly visible example of the influence unions exert in the few remaining states that are not right-to-work and maintain a strong public-sector union presence.

Connecticut remains a key stronghold for unions. It affords them more rights and privileges than most other states, even union-friendly outposts such as neighboring Massachusetts. A number of union resolutions enacted during their international conventions have found legislative and gubernatorial support in Connecticut.

The unions’ effectiveness at putting their own employees or former employees in the legislature, or finding and funding new candidates who support their social and political agenda, is remarkable, particularly in a state that finds itself struggling financially under the weight of public employee pay, pensions and benefits negotiated by those same unions.

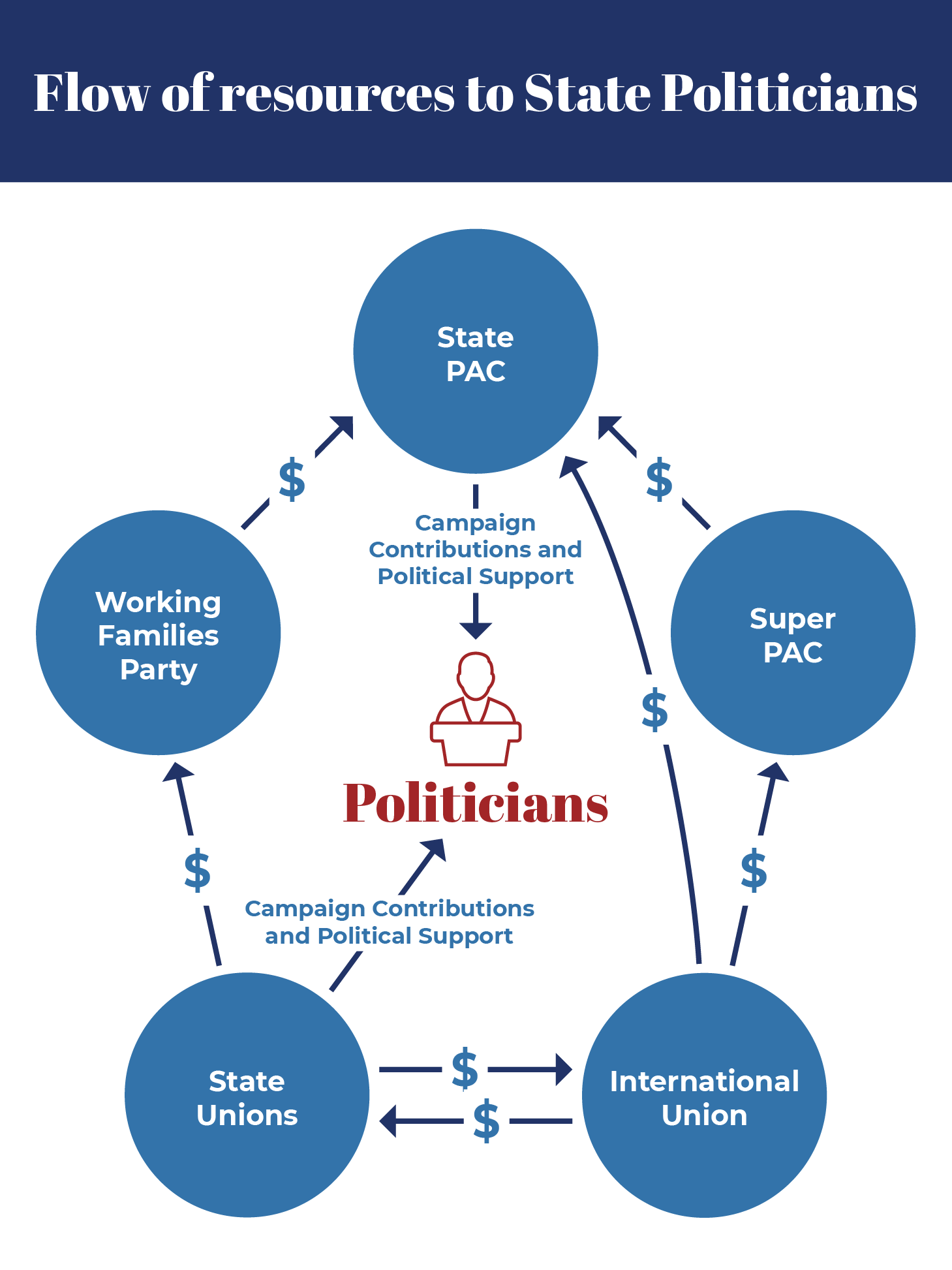

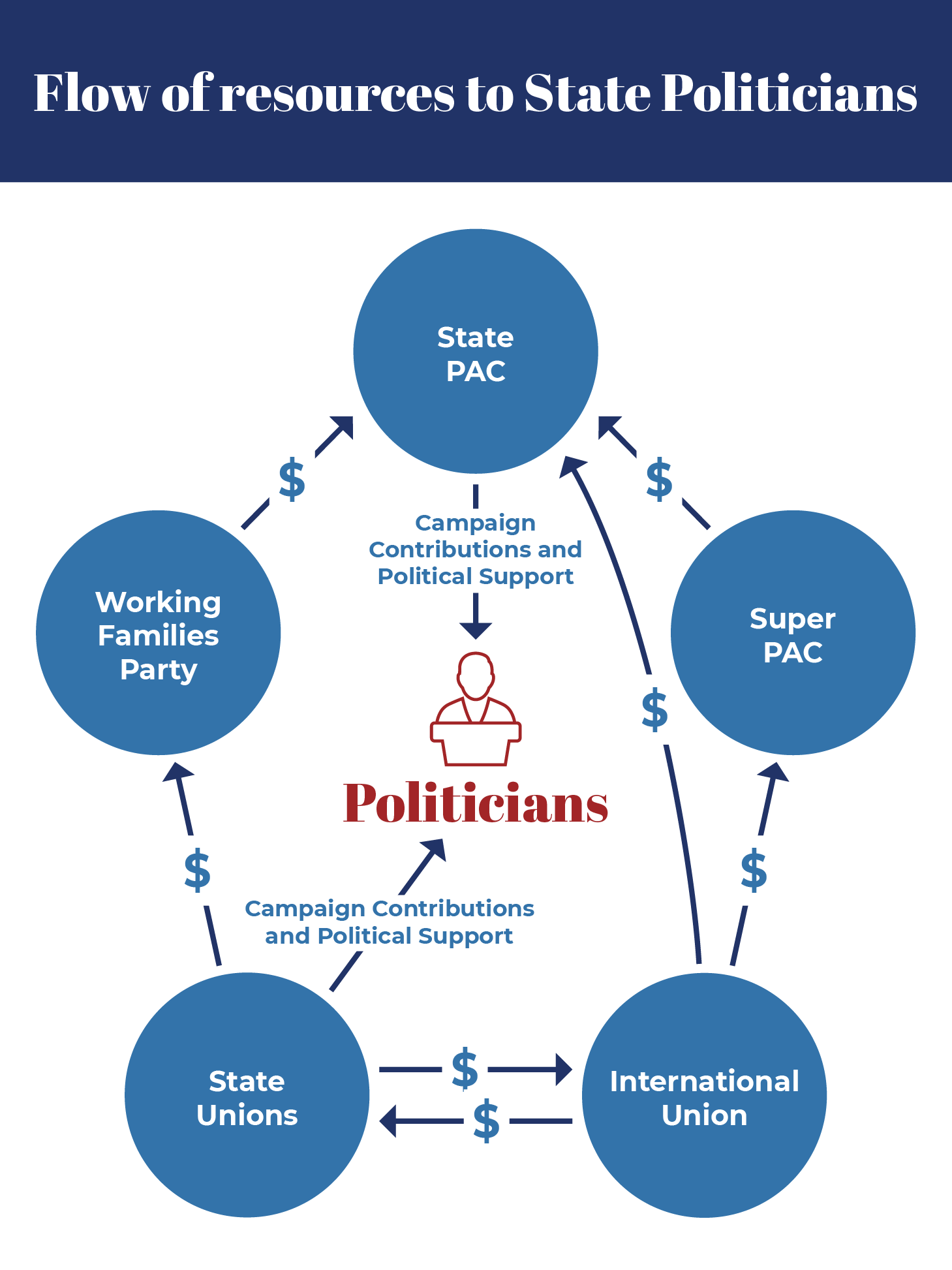

Connecticut lawmakers and candidates attract funding from the state and national levels to maintain their hold over the legislature and its finances.

The previous installment of Conflict of Interest looked at lawmakers whose current or former jobs were inextricably tied to unions.

This installment will examine the circle of money, power and influence between international unions in Washington, D.C., and affiliates in Connecticut.

MONEY MACHINE

During the 2018 election, the Connecticut affiliates of SEIU and AFSCME spent over $1.2 million on advertising and canvassing to elect Gov. Lamont, and state Sens. Kushner and Abrams, along with more minimal spending for some incumbents, including state Sen. Marilyn Moore, D-Bridgeport.

They were not entirely successful. Several of their candidates lost, including Vicki Nardello and Jorge Cabrera.

The union spending was for digital ads through a Washington, D.C., company called 76 Words and another company called Red Horse Strategies out of Brooklyn out of Brooklyn, N.Y. Both firms are used heavily by labor unions during election season.

Paid canvassers came to Connecticut from Base Builder LLC in Minneapolis, Minn. Canvassing literature was purchased from another D.C.-based company called Resonance Campaigns.

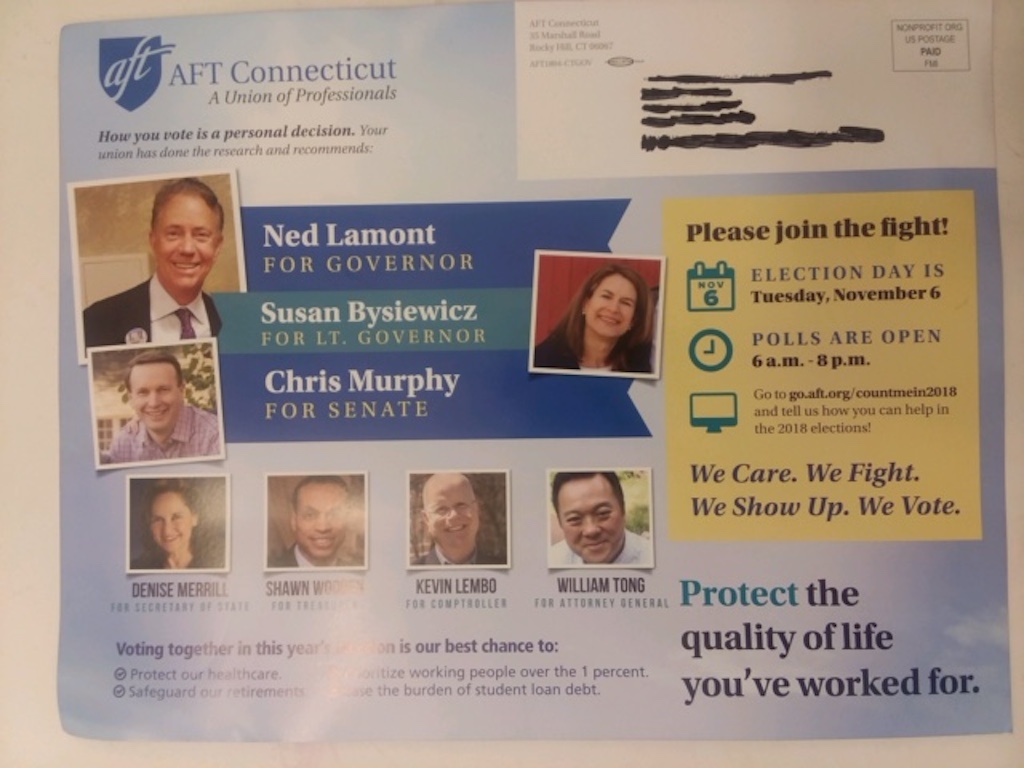

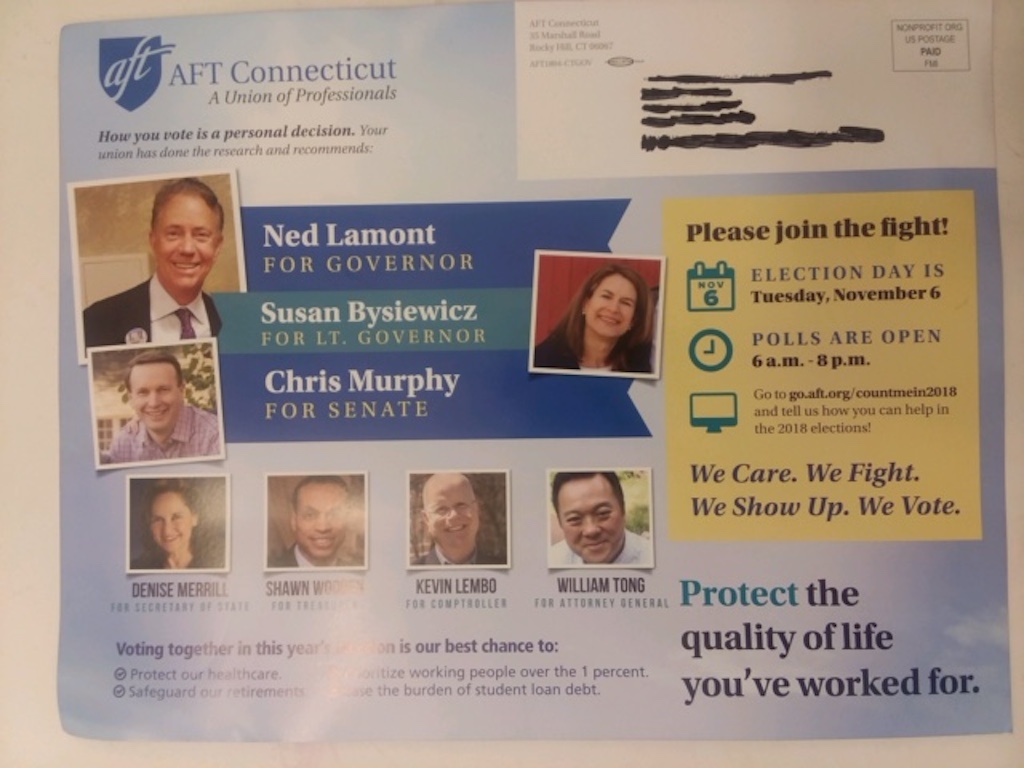

AFSCME Council 4 and the American Federation of Teachers Connecticut, or AFT CT, also sent mailers to their members encouraging them to vote for Lamont, U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy, state Comptroller Kevin Lembo, Secretary of State Denise Merrill, Attorney General William Tong and state Treasurer Shawn Wooden.

AFT Connecticut mail piece.

Overall, their success rate was impressive.

SEIU 1199 accounted for the vast majority of union political spending in Connecticut, racking up a little more than $1 million in independent expenditures. AFSCME Council 4 spent nearly $170,000.

But AFSCME Council 4 didn’t have to do the hard work because D.C.- based AFSCME International was also spending money on Connecticut’s 2018 election – along with other internationals. They were routing the money through national super PACs, which then funneled money to Connecticut political action committees.

Connecticut Values was a 2018 political action committee chaired by Natalie Wagner, a former employee of the Office of Policy and Management under Gov. Malloy.

Connecticut Values received $100,000 from the American Federation of Teachers, AFL-CIO based in Washington, D.C., and another $200,000 from the National Education Association’s Advocacy Fund – also based in D.C. The Connecticut Education Association is the state affiliate of the NEA.

Another $220,000 came to Connecticut Values from the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, a super PAC whose top donor in 2018 was AFSCME International, which contributed $1,050,250.

The DLCC also received six-figure donations from AFT, NEA, SEIU, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, the International Association of Fire Fighters and the United Food & Commercial Workers Union, along with a number of donations from major corporations.

Connecticut Values used the money for independent expenditures supporting a long list of legislative candidates, including several of the same candidates supported by Connecticut’s state unions, such as Sen. Kushner.

The committee also spent money opposing gubernatorial candidate Bob Stefanowski and Republican candidates, including Toni Boucher. Boucher was defeated by Sen. Will Haskell, D-Wilton.

There was also Our Connecticut PAC, chaired by Joseph Shafer, a Washington, D.C., resident and director of independent expenditures for the Democratic Governors Association, or DGA. Shafer had previously served as deputy chief of staff to Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf before taking the helm at DGA.

Our Connecticut was funded entirely by a $125,000 donation from the DGA. The money was only spent on electing Lamont and defeating Stefanowski.

The DGA’s top donors in 2018 were mostly major corporations with three exceptions: AFSCME International, which donated $500,000, the Operating Engineers Union, which donated $420,000, and the United Food & Commercial Workers Union, which donated $290,000.

Although DGA’s top donors in 2018 were largely corporate, this was not always the case.

In 2014, both state and national union money was spent to support the reelection of Gov. Malloy and defeat Republican rival Tom Foley.

The Working Families for Connecticut PAC acted as the conduit for union political spending, taking in $736,446 from state-based unions such as the SEIU CT State Council and SEIU Local 32BJ, as well as from SEIU and AFT international affiliates.

Working Families for Connecticut – which shared the same address as SEIU 1199’s headquarters in Hartford – then spent $1.1 million in independent expenditures to help elect Malloy.

SEIU International’s Committee on Political Education, or COPE, spent another $166,119 on Malloy’s reelection. COPE is the international union’s political fund and is nationally distributed to candidates and political action committees.

But that wasn’t all. The DGA poured $3.8 million into Connecticut Forward, a political action committee dedicated to Malloy’s reelection. Connecticut Forward was one of only five expenditures made by the DGA in 2014.

Unions comprised the vast majority of DGA’s top funders in 2014. AFSCME alone contributed $4.6 million. SEIU contributed $2.9 million, the National Education Association contributed $2.8 million and AFT contributed $2.7 million. Numerous other unions contributed over $1 million to the super PAC.

Malloy had served the unions fairly well during his first term, despite having to negotiate concessions with the State Employees Bargaining Agent Coalition.

He raised taxes to help cover Connecticut’s unfunded pension liabilities in 2011 and issued an executive order to unionize all personal care attendants – only to have his order eviscerated when the U.S. Supreme Court issued their Harris v. Quinn decision. Nevertheless, Malloy’s PCA Workforce Council remains in place and SEIU 1199 is allowed to hold mandatory union orientation for all new personal care attendants.

Former-Gov. Dannel Malloy celebrating with SEIU.

Malloy raised the top state income tax bracket and increased corporate taxes in 2015 and, finally, negotiated a second concessions deal with SEBAC, extending their benefits contract until 2027.

But why all the union focus on a small state like Connecticut?

Connecticut remains a bulwark state for public sector unions. Although only 16% of the total workforce is unionized in Connecticut, 94% of state employees are part of a bargaining unit represented by a union, and that number continues to grow as new groups of public employees are added to union rosters.

During the 2019 session, lawmakers passed a series of 12 arbitrated union agreements that added 608 more employees to the state’s unionized workforce, including attorneys in Connecticut’s tax-collecting department, deputy wardens in Connecticut’s Department of Correction and a variety of managers and engineers – who then received subsequent raises and pay-scale step increases comparable to the raises and increases outlined in Malloy’s 2017 SEBAC agreement.

In 2016, AFT successfully organized assistant attorneys general who were awarded an 11% total pay increase in 2019, which will take effect during the next two years.

There are also unionized municipal employees and teachers throughout the state. The Connecticut AFL-CIO – which includes AFSCME Council 4 and AFT CT – claims over 220,000 members statewide.

But Connecticut’s importance to union leadership may have its roots in national trends and the eroding power of unions in other states.

Union leaders at the national level face a variety of challenges that fuel their commitment to avoid losses in key states where they have spent years cementing their presence and power.

The changes enacted to collective bargaining by former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker in 2011 had a ripple effect throughout the country. Walker severely limited the power of collective bargaining for state employees, capped wage increases, limited the length of contracts to one year and ended the mandatory collection of union dues.

The change was a massive loss for big labor. The fears of something similar happening in Connecticut – which faces continuing budget deficits due to massive unfunded pension liabilities and a population growing angrier over perpetual tax increases – continues to echo in state politics.

Union rally against Scott Walker.

In 2014, then House Majority Leader and AFSCME employee Aresimowicz warned of a Wisconsin moment while speaking to union members at a fundraiser for state Rep. Russ Morin, D-Wethersfield, another union employee who was running for reelection.

Similarly, Gov. Lamont said in his inaugural speech that Connecticut does not need a “Wisconsin moment,” but rather a “Connecticut moment where we show that collective bargaining works.”

More and more states are passing right-to-work legislation that allows all workers the ability to decide whether they want to be part of a union.

Twenty-eight states have right-to-work legislation. In 2016, unions suffered a big loss in West Virginia when the former union stronghold passed right-to-work legislation. That law is currently being debated in court.

In 2018, the Supreme Court issued its Janus v. AFSCME decision, which essentially gave right-to-work guarantees to all public sector workers. The decision has thus far cost unions hundreds of millions of dollars in agency fees from over 200,000 public sector workers across the country.

Combined with regulatory changes enacted by the Trump administration, which ended automatic deduction of union dues from private home health care providers paid through Medicaid, labor unions suddenly find themselves embattled on a national scale. They see a need to solidify their political power in key states such as Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, Washington and Illinois.

Connecticut also offers unions protections that are rarely found in other states. It is one of only four states that sets retirement benefits through collective bargaining rather than in statute, and the state unions vigorously guard that provision.

The benefits contract negotiated between Republican Gov. John Rowland and SEBAC in 1997 was originally a 20-year deal, an amount of time virtually unheard of in collective bargaining agreements.

Union contracts until 2017 were allowed to be passed without a vote by the legislature under Connecticut’s previous “deemed approved” law. The contracts have boosted state workers’ pay and benefits higher than their private sector counterparts. According to a 2015 study, state employees’ total earnings were between 25% and 46% higher than comparative jobs in Connecticut’s private sector.

Through a series of concession agreements with Malloy, SEBAC extended the benefits deal until 2027, making it a 30-year deal that one Connecticut union leader described as “the best and longest public sector pension & healthcare contract in the country,” in a letter to his members.

Changes to pensions, retiree health care and other retirement benefits cannot be changed without approval by the unions. Because those benefits represent one of the largest expenses to Connecticut government, SEBAC controls Connecticut’s fiscal well-being.

Any changes sought by Lamont or future governors will come at a cost.

Connecticut is also the only state which allows labor contracts to supersede state law. Generally, this provision applies to work hours, pay scales, vacation and grievance procedures which are a part of state statute and must be overwritten when a new contract is approved.

Massachusetts allows supersedence for work-related issues such as pay scales and vacation time. However, in Connecticut, labor contracts can supersede other laws, including the state’s Freedom of Information laws.

A Connecticut State Police contract approved during the 2019 session exempts state troopers’ personnel records from public disclosure. A similar contract provision exists for state university and community college professors.

Unions in Connecticut have accrued these and other benefits by solidifying their political power through ensuring the right people are elected to both the legislature and the governor’s office. The unions then ask the people they helped elect to pass legislation that affords further union protections, or to block legislation that could decrease their power and influence.

Connecticut’s unions – in conjunction with the Working Families Party – have been effective at gaining and maintaining legislative influence by running candidates and backing primary opponents for Democratic lawmakers who do not toe the line on union-backed policies, moving the legislature further to the political left.

Many of the policies enacted by union-backed legislators come from the top down as unions set their political agendas during their national conventions.

The resolutions adopted during those conventions have a way of popping up in Connecticut politics.

MONEY AND MARCHING ORDERS

Poor People’s campaign rally

During the 2019 legislative session, state Comptroller Kevin Lembo proposed legislation that would allow small businesses to piggy-back on Connecticut’s state employee health care system as a means of attaining low-cost insurance.

The new program would be formed under Connecticut’s existing structure that allows municipalities to do the same, known as the Connecticut Health Care Partnership Plan 2.0.

The plan is operated by the comptroller in conjunction with the 15-member Health Cost Containment Committee. Of those 15 members, six are union leaders, including chief SEBAC negotiator Dan Livingston and AFSCME Council 4 Executive Director Jody Barr.

The remaining members include two representatives from the Office of Policy and Management, Paul Lombardo of the Connecticut Insurance Department, Theresa DeMattie of Segal Consulting and five administrators from the comptroller’s office.

In the tumult of the legislative session the bill changed to include individual health care plans as well as small businesses, before it died in the waning days of the legislative session when Cigna’s CEO reportedly threatened to move the company out of state – a statement Cigna flatly denied.

Lembo’s bill was a shock to Connecticut’s insurance industry, which pushed back against the legislation saying it “continues down the path toward government-run health insurance.”

House Speaker Aresimowicz, SEBAC’s Livingston, CT AFL-CIO President Luciano and Working Families Party Executive Director Farrell all testified in support of the bill.

The bill itself should not have been surprising as health care insurance costs have been the focus of national political debate and progressive members of Congress have pushed for a single-payer health care system in the United States. It wasn’t the first time the idea had been proposed in Connecticut, although in slightly different forms.

In July 2018 during AFSCME’s 43rd International Convention in Boston, a resolution was passed calling for a state-level single payer health care system. It read, “many states are now proposing legislation to provide funding and a mechanism for such a universal health care system.”

AFSCME resolved to “support state and federal legislation designed to provide universal single payer health care systems.”

During its 2016 convention, SEIU issued a similar resolution to support the Affordable Care Act, “including enacting state-based single-payer models and public options.”

A number of resolutions adopted during international union conventions have found their way to Connecticut’s legislature, including paid family and medical leave, early voting, $15 minimum wage, campaign finance reform, captive audience legislation and measures to push back against the Janus decision.

Whether the push in Connecticut originates from these resolutions, or if the resolutions are reflective of state-based union initiatives, is a chicken-or-egg debate. Unions at both the state and national level respond to changing social and political forces. Higher wages and easier access to early voting have long been part of a national debate.

One recent example shows policies may be developed on a national scale and filtered down to the states.

A Connecticut bill passed out of the Labor and Public Employees Committee in 2019 would have given union leaders the personal contact information for all new state and municipal employees, forced new employees to attend a union orientation within 30 days of their hire, codified dues authorizations into state law and prevented sharing employee information with any organization that might wish to inform employees of their Janus rights.

The bill passed out of the House of Representatives with some modifications following negotiations between Democrats and Republicans, but it was never taken up in the Senate.

A nearly identical bill is now being debated in Illinois, another bastion of public-sector union power.

Illinois Senate Bill 1784 would provide unions with employees’ personal information but block it from being obtained by outside groups; allow union representatives to meet with new hires; codify union dues authorizations into law; give the unions control over informing the employer who is a member and whether an individual has resigned; and limit damages a court can award to a plaintiff over dues deduction issues.

Essentially, it is the same as the bill passed by the Connecticut House of Representatives.

Provisions outlined in both the Connecticut and Illinois bills were passed as resolutions during AFSCME’s 2018 International convention.

According to AFSCME’s “New Employee Outreach – Essential for Our Future” resolution, “AFSCME and affiliates will seek collective bargaining language and appropriate public policy (where possible) mandating union access to new employee orientations, time for individual meetings with new employees, and regularly updated lists of all employees and new hires.”

A second resolution entitled “Public Policies to Build Our Union,” resolved that “AFSCME will seek and implement: Maintenance of dues policies to limit dues and payment revocation periods to promote union financial stability” – essentially limiting time periods when public sector workers could opt out of union membership.

Resolutions to be enacted by AFSCME and other union affiliates at the state level don’t just come with marching orders. Grants are passed on to state unions by the internationals for the purposes of political action and, more broadly, “organizing.”

According to federal filings, AFSCME Council 4 in Connecticut received $269,500 in “State and Local Political Program” grants from AFSCME International between 2014 and 2018.

Another $200,000 was received in 2015 for “General Assistance,” and $100,000 in 2016 for “Organizing Assistance.”

There was also a “Battleground Program” grant in 2011 of $85,795 and a “Recruitment Campaign” grant of $60,000 in 2013.

AFT CT received non-specified grants from the international union of $1.4 million between 2011 and 2018.

SEIU 1199 received $830,157 in grants for organizing from the international union between 2011 and 2018.

According to SEIU 1199’s LM2 reports, the union began making regular monthly contributions to SEIU International’s COPE fund in 2016.

From 2016 to 2018, SEIU 1199 donated $362,501 to COPE. in monthly installments. COPE then used the funds to support state and federal political campaigns and political action committees.

The term “organizing,” however, can mean various things. In Connecticut much of the organizing that AFT and SEIU’s affiliates have engaged in is not necessarily related to union organizing, but rather political and community organizing.

Both AFT CT and SEIU joined with churches, the New Haven People’s Center, Fight for $15 and organizations around the state in 2018 to support the “CT Poor People’s Campaign.” They held a series of rallies and protests called “Moral Mondays” about policies such as a $15 minimum wage, LGBTQ rights, housing issues, environmental issues, gun violence and education.

During one of the rallies, protesters blocked traffic on Capitol Avenue, resulting in a planned arrest of protesters, including AFT CT President Jan Hochadel.

Some of the religious organizations which joined in the Poor People’s Campaign also met with Gov. Lamont to urge passage of the public option health bill, including Rev. Joshua Pawelek of the Unitarian Universalist Society East.

Connecticut’s public-sector unions also endorse and support the Democracy, Unity & Equity (DUE) Justice Coalition, which was also listed as a supporter of the Poor People’s Campaign. The list of supporters for DUE Justice is long, encompassing unions, activist groups, nonprofit organizations and churches.

On May 20, 2019, DUE Justice held a rally for a “Moral Budget” at the Connecticut Capitol. Their platform included paid family and medical leave, a $15 minimum wage, higher taxes on the wealthy, more affordable health care coverage, early voting and, of course, expanding the power of collective bargaining.

STATE AND NATIONAL FORCES

AFL-CIO President Richard Trumpka saying he wants to expand union membership to more non-union groups.

Connecticut’s politics and the policies lawmakers espouse don’t happen in a vacuum. National politics play a big part in how Connecticut’s government operates.

The same goes for Connecticut’s public-sector unions. As one of the few remaining bastions of union strength in the country, state and municipal government unions represent a lifeline for union leaders at the national level.

As of 2018 only 6.6% of the private sector workforce was unionized, but 35.9% of the public-sector workforce was unionized. Holding the reins of government in any state remains crucial to maintaining a union image of power and influence, even as that influence wanes.

Overall union membership across the country is down. The new technology and information jobs occupied by the nation’s millennial generation don’t lend themselves easily to unionization.

Even jobs that were traditional union strongholds are either fading away – such as the coal miners of West Virginia – or face stiff competition from other countries in a global economy, forcing U.S. companies to try to cut costs.

Unions have also found themselves at odds with some of their more blue-collar private sector members as they expand their focus from workers’ rights to a more progressive agenda, including climate change, abortion rights and the anti-Israel Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement.

While this has made them the ideal starting point for young progressive activists looking for work in the social justice movement, it has become harder to convince – for example – auto workers in Tennessee that they should align themselves with these same unions.

Gone is the union mantra of “pay, pensions and health care.” Today, these organizations essentially act as political action committees for progressive politics, using their money machine to push social issues that, traditionally, were outside their wheelhouse.

Name any progressive social or political movement and you will likely find both state and national union affiliates backing it in an attempt to secure future political power.

This shift may explain why union power is now centralized in the government worker sector rather than in the traditional, blue-collar private sector. Progressives love to grow government; growing government means more union workers and more union power.

Unions’ shift to becoming progressive political advocacy groups has cost them as some union members – such as Mark Janus of the Janus v. AFSCME decision or Rebecca Friedrichs of the preceding Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association – push back against financially supporting politics with which they don’t agree.

In essence, the unions picked a political side on issues that have little to do with pay, pensions and benefits. In a nation that has become politically divided and increasingly angry, picking one side can mean alienating the other.

Unlike leadership, union members are not a unified political bloc; they are individuals who think for themselves and sometimes bristle at the idea of receiving their political positions from the top down. That is proving problematic for unions at the national level, but there are other problems.

The success of public-sector unions in carving out benefits for themselves and their members is being challenged in some states, including Connecticut.

States with deeply entrenched and politically connected public sector unions are more likely to face fiscal problems stemming from massive pension and retiree health care benefit liabilities.

Connecticut, Illinois and New Jersey are all states with hefty union power. They are also states that face high taxes, high costs of living, continuing budget problems, sky-high pension costs and declining populations as residents decamp for more financially stable – and often warmer – climes.

Connecticut faces the added pressure of an economy which has remained stagnant since the 2008 recession and the loss of some major corporate headquarters, further dampening the state’s national image.

Those factors put enormous pressure on lawmakers. They must somehow balance budgets without raising taxes and angering voters, while also accounting for increased labor and legacy costs.

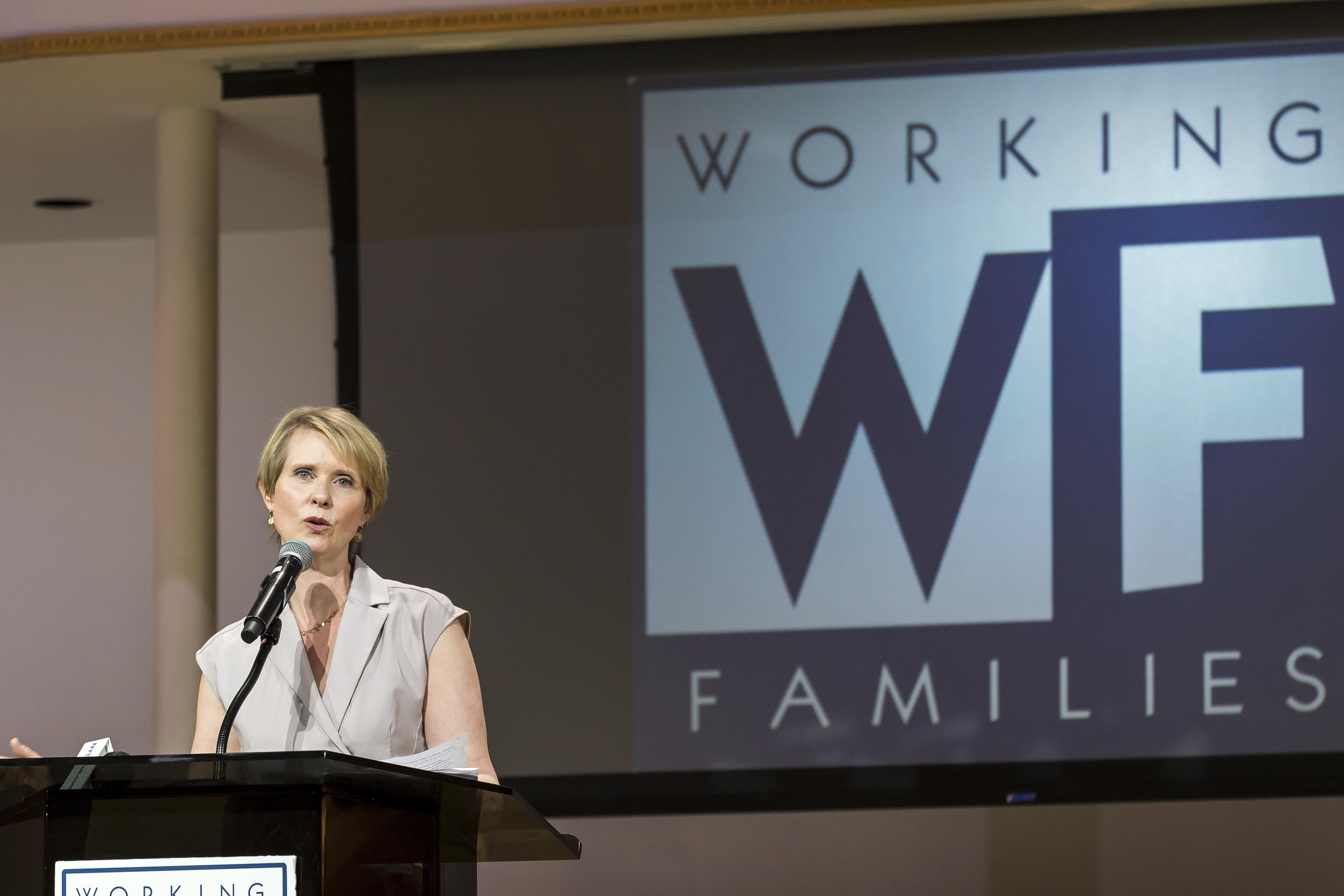

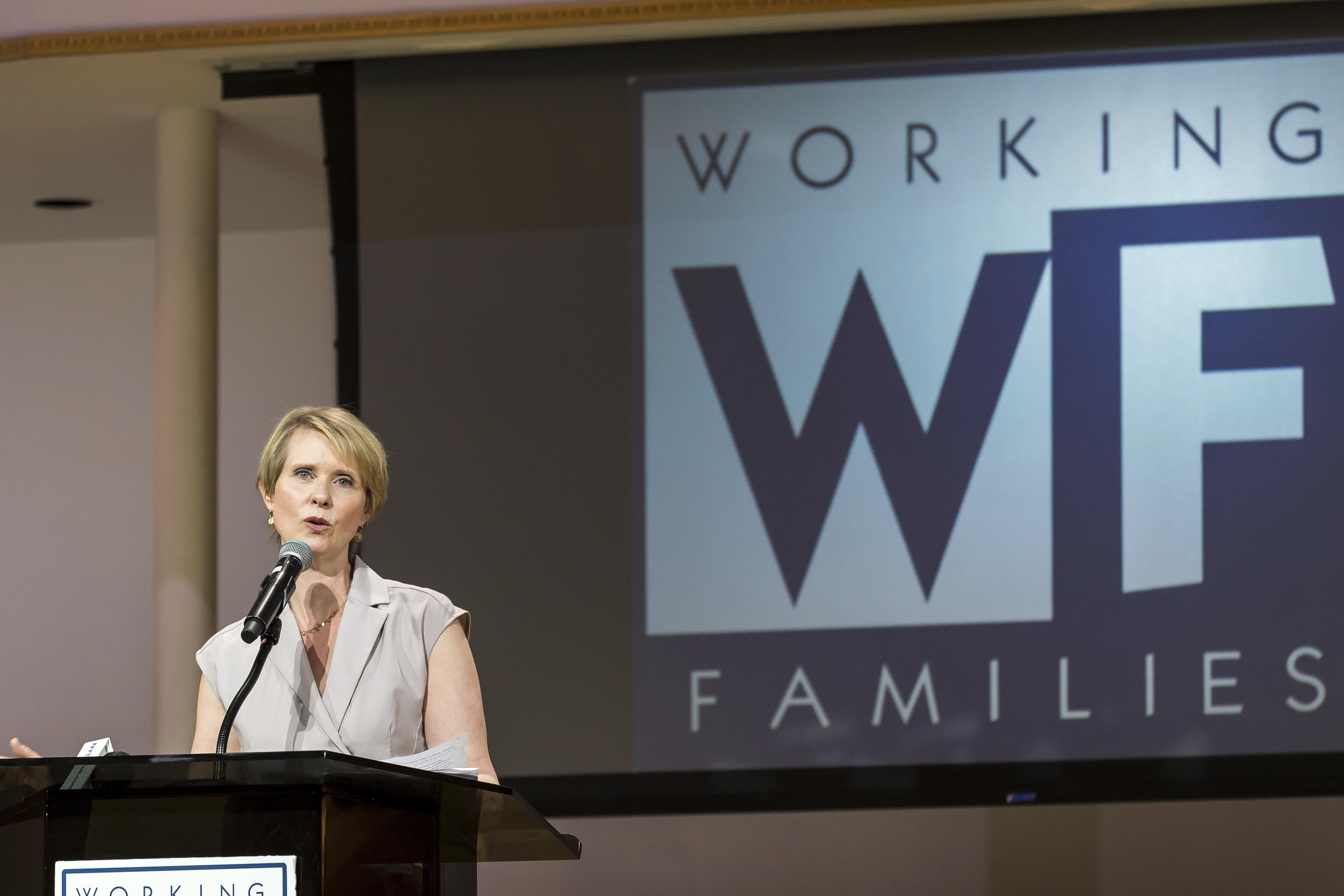

Attempts at reforming pensions or pushing back against public-sector unions are likewise met with fierce resistance, and many lawmakers, particularly on the Democratic Party side of the aisle, risk losing reelection support from the unions’ powerful money machine or a primary fight from a candidate drafted by the Working Families Party.

Working Families Party New York endorses Cynthia Nixon for governor to primary against Andrew Cuomo.

Connecticut’s 2018 election results saw a large swing to the political left. Many blamed the Trump effect, saying the contentious and controversial president energized the left-of-center base in Connecticut. Democrats gained seats in the state House and Senate for the first time in a decade.

The newly formed Progressive Caucus now claims 46 members – including current and former union employees – and the progressives’ stated political goals match the unions’ at both the state and national level.

The Progressive Caucus pushed through a $15 minimum wage and a paid family and medical leave program and continues to push for higher taxes on the wealthy residents of Connecticut.

However, even with a powerful caucus on their side and 14 current or former employees elected to the General Assembly and occupying influential positions in the legislature, not all of the unions’ goals could be reached during the 2019 session.

Some lawmakers, including Gov. Lamont, feared increasing the top tax rate would continue Connecticut’s loss of higher-income individuals and families.

Connecticut is indeed a battleground state for public-sector unions. Their fight now is not with the legislature, but with socioeconomic forces in both the state and the country.

Public-sector unions will not relinquish the battle anytime soon and will continue to pour money into Connecticut’s elections and legislature as they have for years. They will continue to hold tight to the SEBAC agreement for the next eight years, and possibly more depending on negotiations with the governor.

But if the state of Connecticut can’t find a way to fix its finances before the next recession, those union leaders may find themselves waging a war they can’t win and protecting a stronghold state where no one wants to live, work or raise a family.

And that could be bad for everybody, including the unions. There is little use, or money, in guarding something no one wants.

Read Part 1 of this series: Conflict of Interest? Union influence in Connecticut Government.

On May 9, following a 14-hour debate in the Connecticut House of Representatives, state Rep. Robyn Porter, D-New Haven, delivered an impassioned final speech in support of raising the state’s minimum wage to $15 per hour.

She had been on her feet through the night fielding questions from Republicans, who used the opportunity to show their grit in the face of an overwhelming Democratic majority. Porter only took occasional breaks, letting a fellow Democrat step in.

She had been fighting for the minimum wage increase for years, and this year it would finally pass.

Porter, a former employee of the Communications Workers of America, thanked her union brothers and sisters on the House floor as House Speaker Joe Aresimowicz, an employee of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Council 4, readied to call the vote.

Everyone – both legislators and those watching at the Capitol – already knew how the vote would turn out. Raising Connecticut’s minimum wage to $15 per hour had been a sought-after goal for many Democrats since the state’s minimum wage hit $10.10 per hour in 2017. A bill to raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour was voted out of the Labor and Public Employees Committee multiple times only to die later in the session.

Laphonza Butler, President of SEIU ULTCW, the United Long Term Care Workers’ Union joins workers demanding the Los Angeles City Council to vote to raise the minimum wage in 2015.

Now, with solid Democratic majorities in both the House and Senate, as well as a new Democratic governor who said he would support the measure, Connecticut was poised to become the sixth state to pass a $15 minimum wage.

But the Fight for $15 in Connecticut wasn’t just pushed by lawmakers: it was a primary goal of public-sector union leaders who repeatedly pushed the bill forward in the Capitol and lobbied legislators to pass it.

State union leaders advocated the increase, but it was part of a national movement spurred by national labor unions out of Washington, D.C. They recognized they could be more effective by pushing minimum wage increases at the state rather than the federal level.

The Fight for $15 began in 2012 when the Service Employees International Union attempted to organize fast food workers in New York City. According to one organizer, the $15 goal was more a matter of coming up with a catchy slogan and finding the right number rather than a research-backed need.

Kendall Fells, an SEIU union organizer who helped kick-start the movement in New York City, said $15 was settled on by fast-food workers because $10 was too low and $20 was too high.

The coordinated, $90 million Fight for $15 campaign quickly spread to other cities and eventually states, including California, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Massachusetts and finally Connecticut.

No sooner did Connecticut’s minimum wage hit $10.10 per hour – an increase signed into law by Gov. Dannel Malloy in 2014 – than bills to increase the wage to $15 started getting passed out of the Labor and Public Employees Committee with the full backing of Connecticut Democrats, labor union leaders and a host of union-backed organizations such as the Working Families Party, the Connecticut Citizen Action Group and Connecticut Voices for Children.

The increase was opposed by business association leaders and organizations, who argued the increase was too much, too fast, and would ultimately cost jobs and raise the cost of goods and services in the state. Connecticut employers were facing a 72.4% increase in the state’s minimum wage over 10 years.

Forum Plastics – a medical manufacturing company based in the beleaguered city of Waterbury – issued a warning telling lawmakers they would be forced to move out of state if the $15 minimum wage was passed.

The $15 minimum wage was hardly an economic panacea elsewhere: some workers earned more money while others lost their jobs or faced reduced hours and benefits. That likely would not bode well for a state such as Connecticut, which continues to face economic stagnation since the 2008 recession. The state’s job growth and personal income growth ranked among the lowest in the nation and Connecticut ranked third year-over-year for residents moving to other states, many in search of work.

But the Fight for $15 was not a fight for an improved economy or for more jobs. Rather it was a political fight meant to boost union power through organizing, rallying, and bending state and local governments to their will, regardless of the outcome.

While SEIU organized the movement nationally, AFSCME International, the American Federation for Teachers and the AFL-CIO all signed on to Fight for $15 through resolutions passed at their international conventions.

In 2014, Executive Director of AFSCME Council 4 in Connecticut, Sal Luciano, proposed and passed a resolution at AFSCME’s 2014 convention in Chicago to pressure the Obama administration to increase the federal minimum wage to $10.10 per hour, matching Connecticut’s increase.

That never happened. By 2016, AFSCME adopted a new resolution to support the Fight for $15 at all government levels and to urge “all candidates on the local, state and federal level to make support for a $15 per hour minimum wage a prominent part of their campaign platform, and to work diligently to pass legislation once elected to office.”

The Fight for $15 stalled in the Connecticut legislature for two years until a sweeping victory by Democrats in the 2018 elections secured their majorities in the House and Senate.

The electoral sweep was largely unexpected. Out-going governor Malloy was deeply unpopular, the state was stuck in an economic malaise and trailed the rest of the country in job growth, taxes had been raised significantly in 2011 and 2015, and the specter of unfunded pension and retirement liabilities for both state employees and teachers threatened to continue the cycle of budget deficits and tax increases.

In 2018, the Connecticut Senate was tied between Republicans and Democrats and there was only a slim Democratic majority in the House. Gubernatorial candidate Ned Lamont faced a tough fight to emerge from Malloy’s shadow.

Fear of what a Republican governor or Senate victory could mean for their legislative agenda mobilized Connecticut’s public-sector unions. They poured money into the elections.

SEIU 1199 alone spent over $1 million in independent expenditures – money spent to promote a candidate without coordinating with the candidate’s campaign – to elect Lamont governor and secure Senate victories for Mary Abrams, D-Meriden, and former union organizer Julie Kushner, D-Danbury.

AFSCME Council 4 also spent on Lamont, Abrams and Kushner, although far less than SEIU.

AFSCME Council 4 also ponied up money to help elect former-state Reps. Matthew Lesser, D-Middletown, and James Maroney, D-Milford, to the Senate and used independent expenditures to keep incumbents in office including Sens. Steve Cassano, D-Manchester, Mae Flexer, D-Killingly, and Christine Cohen, D-Guilford.

Although the unions didn’t spend reportable money on his election, they held rallies with Attorney General candidate William Tong. He eventually won his election and went on to offer his support for so-called “captive audience” legislation, which had been previously defeated in the legislature because it ran afoul of national labor law.

But union money to support and oppose candidates in Connecticut’s 2018 elections didn’t just come from unions inside Connecticut.

Both marching orders and money flowed from the international union affiliates in Washington, D.C., down to Connecticut, as it had in previous years.

The Fight for $15 is just one highly visible example of the influence unions exert in the few remaining states that are not right-to-work and maintain a strong public-sector union presence.

Connecticut remains a key stronghold for unions. It affords them more rights and privileges than most other states, even union-friendly outposts such as neighboring Massachusetts. A number of union resolutions enacted during their international conventions have found legislative and gubernatorial support in Connecticut.

The unions’ effectiveness at putting their own employees or former employees in the legislature, or finding and funding new candidates who support their social and political agenda, is remarkable, particularly in a state that finds itself struggling financially under the weight of public employee pay, pensions and benefits negotiated by those same unions.

Connecticut lawmakers and candidates attract funding from the state and national levels to maintain their hold over the legislature and its finances.

The previous installment of Conflict of Interest looked at lawmakers whose current or former jobs were inextricably tied to unions.

This installment will examine the circle of money, power and influence between international unions in Washington, D.C., and affiliates in Connecticut.

MONEY MACHINE

During the 2018 election, the Connecticut affiliates of SEIU and AFSCME spent over $1.2 million on advertising and canvassing to elect Gov. Lamont, and state Sens. Kushner and Abrams, along with more minimal spending for some incumbents, including state Sen. Marilyn Moore, D-Bridgeport.

They were not entirely successful. Several of their candidates lost, including Vicki Nardello and Jorge Cabrera.

The union spending was for digital ads through a Washington, D.C., company called 76 Words and another company called Red Horse Strategies out of Brooklyn out of Brooklyn, N.Y. Both firms are used heavily by labor unions during election season.

Paid canvassers came to Connecticut from Base Builder LLC in Minneapolis, Minn. Canvassing literature was purchased from another D.C.-based company called Resonance Campaigns.

AFSCME Council 4 and the American Federation of Teachers Connecticut, or AFT CT, also sent mailers to their members encouraging them to vote for Lamont, U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy, state Comptroller Kevin Lembo, Secretary of State Denise Merrill, Attorney General William Tong and state Treasurer Shawn Wooden.

AFT Connecticut mail piece.

Overall, their success rate was impressive.

SEIU 1199 accounted for the vast majority of union political spending in Connecticut, racking up a little more than $1 million in independent expenditures. AFSCME Council 4 spent nearly $170,000.

But AFSCME Council 4 didn’t have to do the hard work because D.C.- based AFSCME International was also spending money on Connecticut’s 2018 election – along with other internationals. They were routing the money through national super PACs, which then funneled money to Connecticut political action committees.

Connecticut Values was a 2018 political action committee chaired by Natalie Wagner, a former employee of the Office of Policy and Management under Gov. Malloy.

Connecticut Values received $100,000 from the American Federation of Teachers, AFL-CIO based in Washington, D.C., and another $200,000 from the National Education Association’s Advocacy Fund – also based in D.C. The Connecticut Education Association is the state affiliate of the NEA.

Another $220,000 came to Connecticut Values from the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, a super PAC whose top donor in 2018 was AFSCME International, which contributed $1,050,250.

The DLCC also received six-figure donations from AFT, NEA, SEIU, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, the International Association of Fire Fighters and the United Food & Commercial Workers Union, along with a number of donations from major corporations.

Connecticut Values used the money for independent expenditures supporting a long list of legislative candidates, including several of the same candidates supported by Connecticut’s state unions, such as Sen. Kushner.

The committee also spent money opposing gubernatorial candidate Bob Stefanowski and Republican candidates, including Toni Boucher. Boucher was defeated by Sen. Will Haskell, D-Wilton.

There was also Our Connecticut PAC, chaired by Joseph Shafer, a Washington, D.C., resident and director of independent expenditures for the Democratic Governors Association, or DGA. Shafer had previously served as deputy chief of staff to Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf before taking the helm at DGA.

Our Connecticut was funded entirely by a $125,000 donation from the DGA. The money was only spent on electing Lamont and defeating Stefanowski.

The DGA’s top donors in 2018 were mostly major corporations with three exceptions: AFSCME International, which donated $500,000, the Operating Engineers Union, which donated $420,000, and the United Food & Commercial Workers Union, which donated $290,000.

Although DGA’s top donors in 2018 were largely corporate, this was not always the case.

In 2014, both state and national union money was spent to support the reelection of Gov. Malloy and defeat Republican rival Tom Foley.

The Working Families for Connecticut PAC acted as the conduit for union political spending, taking in $736,446 from state-based unions such as the SEIU CT State Council and SEIU Local 32BJ, as well as from SEIU and AFT international affiliates.

Working Families for Connecticut – which shared the same address as SEIU 1199’s headquarters in Hartford – then spent $1.1 million in independent expenditures to help elect Malloy.

SEIU International’s Committee on Political Education, or COPE, spent another $166,119 on Malloy’s reelection. COPE is the international union’s political fund and is nationally distributed to candidates and political action committees.

But that wasn’t all. The DGA poured $3.8 million into Connecticut Forward, a political action committee dedicated to Malloy’s reelection. Connecticut Forward was one of only five expenditures made by the DGA in 2014.

Unions comprised the vast majority of DGA’s top funders in 2014. AFSCME alone contributed $4.6 million. SEIU contributed $2.9 million, the National Education Association contributed $2.8 million and AFT contributed $2.7 million. Numerous other unions contributed over $1 million to the super PAC.

Malloy had served the unions fairly well during his first term, despite having to negotiate concessions with the State Employees Bargaining Agent Coalition.

He raised taxes to help cover Connecticut’s unfunded pension liabilities in 2011 and issued an executive order to unionize all personal care attendants – only to have his order eviscerated when the U.S. Supreme Court issued their Harris v. Quinn decision. Nevertheless, Malloy’s PCA Workforce Council remains in place and SEIU 1199 is allowed to hold mandatory union orientation for all new personal care attendants.

Former-Gov. Dannel Malloy celebrating with SEIU.

Malloy raised the top state income tax bracket and increased corporate taxes in 2015 and, finally, negotiated a second concessions deal with SEBAC, extending their benefits contract until 2027.

But why all the union focus on a small state like Connecticut?

Connecticut remains a bulwark state for public sector unions. Although only 16% of the total workforce is unionized in Connecticut, 94% of state employees are part of a bargaining unit represented by a union, and that number continues to grow as new groups of public employees are added to union rosters.

During the 2019 session, lawmakers passed a series of 12 arbitrated union agreements that added 608 more employees to the state’s unionized workforce, including attorneys in Connecticut’s tax-collecting department, deputy wardens in Connecticut’s Department of Correction and a variety of managers and engineers – who then received subsequent raises and pay-scale step increases comparable to the raises and increases outlined in Malloy’s 2017 SEBAC agreement.

In 2016, AFT successfully organized assistant attorneys general who were awarded an 11% total pay increase in 2019, which will take effect during the next two years.

There are also unionized municipal employees and teachers throughout the state. The Connecticut AFL-CIO – which includes AFSCME Council 4 and AFT CT – claims over 220,000 members statewide.

But Connecticut’s importance to union leadership may have its roots in national trends and the eroding power of unions in other states.

Union leaders at the national level face a variety of challenges that fuel their commitment to avoid losses in key states where they have spent years cementing their presence and power.

The changes enacted to collective bargaining by former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker in 2011 had a ripple effect throughout the country. Walker severely limited the power of collective bargaining for state employees, capped wage increases, limited the length of contracts to one year and ended the mandatory collection of union dues.

The change was a massive loss for big labor. The fears of something similar happening in Connecticut – which faces continuing budget deficits due to massive unfunded pension liabilities and a population growing angrier over perpetual tax increases – continues to echo in state politics.

Union rally against Scott Walker.

In 2014, then House Majority Leader and AFSCME employee Aresimowicz warned of a Wisconsin moment while speaking to union members at a fundraiser for state Rep. Russ Morin, D-Wethersfield, another union employee who was running for reelection.

Similarly, Gov. Lamont said in his inaugural speech that Connecticut does not need a “Wisconsin moment,” but rather a “Connecticut moment where we show that collective bargaining works.”

More and more states are passing right-to-work legislation that allows all workers the ability to decide whether they want to be part of a union.

Twenty-eight states have right-to-work legislation. In 2016, unions suffered a big loss in West Virginia when the former union stronghold passed right-to-work legislation. That law is currently being debated in court.

In 2018, the Supreme Court issued its Janus v. AFSCME decision, which essentially gave right-to-work guarantees to all public sector workers. The decision has thus far cost unions hundreds of millions of dollars in agency fees from over 200,000 public sector workers across the country.

Combined with regulatory changes enacted by the Trump administration, which ended automatic deduction of union dues from private home health care providers paid through Medicaid, labor unions suddenly find themselves embattled on a national scale. They see a need to solidify their political power in key states such as Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, Washington and Illinois.

Connecticut also offers unions protections that are rarely found in other states. It is one of only four states that sets retirement benefits through collective bargaining rather than in statute, and the state unions vigorously guard that provision.

The benefits contract negotiated between Republican Gov. John Rowland and SEBAC in 1997 was originally a 20-year deal, an amount of time virtually unheard of in collective bargaining agreements.

Union contracts until 2017 were allowed to be passed without a vote by the legislature under Connecticut’s previous “deemed approved” law. The contracts have boosted state workers’ pay and benefits higher than their private sector counterparts. According to a 2015 study, state employees’ total earnings were between 25% and 46% higher than comparative jobs in Connecticut’s private sector.

Through a series of concession agreements with Malloy, SEBAC extended the benefits deal until 2027, making it a 30-year deal that one Connecticut union leader described as “the best and longest public sector pension & healthcare contract in the country,” in a letter to his members.

Changes to pensions, retiree health care and other retirement benefits cannot be changed without approval by the unions. Because those benefits represent one of the largest expenses to Connecticut government, SEBAC controls Connecticut’s fiscal well-being.

Any changes sought by Lamont or future governors will come at a cost.

Connecticut is also the only state which allows labor contracts to supersede state law. Generally, this provision applies to work hours, pay scales, vacation and grievance procedures which are a part of state statute and must be overwritten when a new contract is approved.

Massachusetts allows supersedence for work-related issues such as pay scales and vacation time. However, in Connecticut, labor contracts can supersede other laws, including the state’s Freedom of Information laws.

A Connecticut State Police contract approved during the 2019 session exempts state troopers’ personnel records from public disclosure. A similar contract provision exists for state university and community college professors.

Unions in Connecticut have accrued these and other benefits by solidifying their political power through ensuring the right people are elected to both the legislature and the governor’s office. The unions then ask the people they helped elect to pass legislation that affords further union protections, or to block legislation that could decrease their power and influence.

Connecticut’s unions – in conjunction with the Working Families Party – have been effective at gaining and maintaining legislative influence by running candidates and backing primary opponents for Democratic lawmakers who do not toe the line on union-backed policies, moving the legislature further to the political left.

Many of the policies enacted by union-backed legislators come from the top down as unions set their political agendas during their national conventions.

The resolutions adopted during those conventions have a way of popping up in Connecticut politics.

MONEY AND MARCHING ORDERS

Poor People’s campaign rally

During the 2019 legislative session, state Comptroller Kevin Lembo proposed legislation that would allow small businesses to piggy-back on Connecticut’s state employee health care system as a means of attaining low-cost insurance.

The new program would be formed under Connecticut’s existing structure that allows municipalities to do the same, known as the Connecticut Health Care Partnership Plan 2.0.

The plan is operated by the comptroller in conjunction with the 15-member Health Cost Containment Committee. Of those 15 members, six are union leaders, including chief SEBAC negotiator Dan Livingston and AFSCME Council 4 Executive Director Jody Barr.

The remaining members include two representatives from the Office of Policy and Management, Paul Lombardo of the Connecticut Insurance Department, Theresa DeMattie of Segal Consulting and five administrators from the comptroller’s office.

In the tumult of the legislative session the bill changed to include individual health care plans as well as small businesses, before it died in the waning days of the legislative session when Cigna’s CEO reportedly threatened to move the company out of state – a statement Cigna flatly denied.

Lembo’s bill was a shock to Connecticut’s insurance industry, which pushed back against the legislation saying it “continues down the path toward government-run health insurance.”

House Speaker Aresimowicz, SEBAC’s Livingston, CT AFL-CIO President Luciano and Working Families Party Executive Director Farrell all testified in support of the bill.

The bill itself should not have been surprising as health care insurance costs have been the focus of national political debate and progressive members of Congress have pushed for a single-payer health care system in the United States. It wasn’t the first time the idea had been proposed in Connecticut, although in slightly different forms.

In July 2018 during AFSCME’s 43rd International Convention in Boston, a resolution was passed calling for a state-level single payer health care system. It read, “many states are now proposing legislation to provide funding and a mechanism for such a universal health care system.”

AFSCME resolved to “support state and federal legislation designed to provide universal single payer health care systems.”

During its 2016 convention, SEIU issued a similar resolution to support the Affordable Care Act, “including enacting state-based single-payer models and public options.”

A number of resolutions adopted during international union conventions have found their way to Connecticut’s legislature, including paid family and medical leave, early voting, $15 minimum wage, campaign finance reform, captive audience legislation and measures to push back against the Janus decision.

Whether the push in Connecticut originates from these resolutions, or if the resolutions are reflective of state-based union initiatives, is a chicken-or-egg debate. Unions at both the state and national level respond to changing social and political forces. Higher wages and easier access to early voting have long been part of a national debate.

One recent example shows policies may be developed on a national scale and filtered down to the states.

A Connecticut bill passed out of the Labor and Public Employees Committee in 2019 would have given union leaders the personal contact information for all new state and municipal employees, forced new employees to attend a union orientation within 30 days of their hire, codified dues authorizations into state law and prevented sharing employee information with any organization that might wish to inform employees of their Janus rights.

The bill passed out of the House of Representatives with some modifications following negotiations between Democrats and Republicans, but it was never taken up in the Senate.

A nearly identical bill is now being debated in Illinois, another bastion of public-sector union power.

Illinois Senate Bill 1784 would provide unions with employees’ personal information but block it from being obtained by outside groups; allow union representatives to meet with new hires; codify union dues authorizations into law; give the unions control over informing the employer who is a member and whether an individual has resigned; and limit damages a court can award to a plaintiff over dues deduction issues.

Essentially, it is the same as the bill passed by the Connecticut House of Representatives.

Provisions outlined in both the Connecticut and Illinois bills were passed as resolutions during AFSCME’s 2018 International convention.

According to AFSCME’s “New Employee Outreach – Essential for Our Future” resolution, “AFSCME and affiliates will seek collective bargaining language and appropriate public policy (where possible) mandating union access to new employee orientations, time for individual meetings with new employees, and regularly updated lists of all employees and new hires.”

A second resolution entitled “Public Policies to Build Our Union,” resolved that “AFSCME will seek and implement: Maintenance of dues policies to limit dues and payment revocation periods to promote union financial stability” – essentially limiting time periods when public sector workers could opt out of union membership.

Resolutions to be enacted by AFSCME and other union affiliates at the state level don’t just come with marching orders. Grants are passed on to state unions by the internationals for the purposes of political action and, more broadly, “organizing.”

According to federal filings, AFSCME Council 4 in Connecticut received $269,500 in “State and Local Political Program” grants from AFSCME International between 2014 and 2018.

Another $200,000 was received in 2015 for “General Assistance,” and $100,000 in 2016 for “Organizing Assistance.”

There was also a “Battleground Program” grant in 2011 of $85,795 and a “Recruitment Campaign” grant of $60,000 in 2013.

AFT CT received non-specified grants from the international union of $1.4 million between 2011 and 2018.

SEIU 1199 received $830,157 in grants for organizing from the international union between 2011 and 2018.

According to SEIU 1199’s LM2 reports, the union began making regular monthly contributions to SEIU International’s COPE fund in 2016.

From 2016 to 2018, SEIU 1199 donated $362,501 to COPE. in monthly installments. COPE then used the funds to support state and federal political campaigns and political action committees.

The term “organizing,” however, can mean various things. In Connecticut much of the organizing that AFT and SEIU’s affiliates have engaged in is not necessarily related to union organizing, but rather political and community organizing.

Both AFT CT and SEIU joined with churches, the New Haven People’s Center, Fight for $15 and organizations around the state in 2018 to support the “CT Poor People’s Campaign.” They held a series of rallies and protests called “Moral Mondays” about policies such as a $15 minimum wage, LGBTQ rights, housing issues, environmental issues, gun violence and education.

During one of the rallies, protesters blocked traffic on Capitol Avenue, resulting in a planned arrest of protesters, including AFT CT President Jan Hochadel.

Some of the religious organizations which joined in the Poor People’s Campaign also met with Gov. Lamont to urge passage of the public option health bill, including Rev. Joshua Pawelek of the Unitarian Universalist Society East.

Connecticut’s public-sector unions also endorse and support the Democracy, Unity & Equity (DUE) Justice Coalition, which was also listed as a supporter of the Poor People’s Campaign. The list of supporters for DUE Justice is long, encompassing unions, activist groups, nonprofit organizations and churches.

On May 20, 2019, DUE Justice held a rally for a “Moral Budget” at the Connecticut Capitol. Their platform included paid family and medical leave, a $15 minimum wage, higher taxes on the wealthy, more affordable health care coverage, early voting and, of course, expanding the power of collective bargaining.

STATE AND NATIONAL FORCES

AFL-CIO President Richard Trumpka saying he wants to expand union membership to more non-union groups.

Connecticut’s politics and the policies lawmakers espouse don’t happen in a vacuum. National politics play a big part in how Connecticut’s government operates.

The same goes for Connecticut’s public-sector unions. As one of the few remaining bastions of union strength in the country, state and municipal government unions represent a lifeline for union leaders at the national level.

As of 2018 only 6.6% of the private sector workforce was unionized, but 35.9% of the public-sector workforce was unionized. Holding the reins of government in any state remains crucial to maintaining a union image of power and influence, even as that influence wanes.

Overall union membership across the country is down. The new technology and information jobs occupied by the nation’s millennial generation don’t lend themselves easily to unionization.

Even jobs that were traditional union strongholds are either fading away – such as the coal miners of West Virginia – or face stiff competition from other countries in a global economy, forcing U.S. companies to try to cut costs.

Unions have also found themselves at odds with some of their more blue-collar private sector members as they expand their focus from workers’ rights to a more progressive agenda, including climate change, abortion rights and the anti-Israel Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement.

While this has made them the ideal starting point for young progressive activists looking for work in the social justice movement, it has become harder to convince – for example – auto workers in Tennessee that they should align themselves with these same unions.

Gone is the union mantra of “pay, pensions and health care.” Today, these organizations essentially act as political action committees for progressive politics, using their money machine to push social issues that, traditionally, were outside their wheelhouse.

Name any progressive social or political movement and you will likely find both state and national union affiliates backing it in an attempt to secure future political power.

This shift may explain why union power is now centralized in the government worker sector rather than in the traditional, blue-collar private sector. Progressives love to grow government; growing government means more union workers and more union power.

Unions’ shift to becoming progressive political advocacy groups has cost them as some union members – such as Mark Janus of the Janus v. AFSCME decision or Rebecca Friedrichs of the preceding Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association – push back against financially supporting politics with which they don’t agree.

In essence, the unions picked a political side on issues that have little to do with pay, pensions and benefits. In a nation that has become politically divided and increasingly angry, picking one side can mean alienating the other.

Unlike leadership, union members are not a unified political bloc; they are individuals who think for themselves and sometimes bristle at the idea of receiving their political positions from the top down. That is proving problematic for unions at the national level, but there are other problems.

The success of public-sector unions in carving out benefits for themselves and their members is being challenged in some states, including Connecticut.

States with deeply entrenched and politically connected public sector unions are more likely to face fiscal problems stemming from massive pension and retiree health care benefit liabilities.

Connecticut, Illinois and New Jersey are all states with hefty union power. They are also states that face high taxes, high costs of living, continuing budget problems, sky-high pension costs and declining populations as residents decamp for more financially stable – and often warmer – climes.

Connecticut faces the added pressure of an economy which has remained stagnant since the 2008 recession and the loss of some major corporate headquarters, further dampening the state’s national image.

Those factors put enormous pressure on lawmakers. They must somehow balance budgets without raising taxes and angering voters, while also accounting for increased labor and legacy costs.

Attempts at reforming pensions or pushing back against public-sector unions are likewise met with fierce resistance, and many lawmakers, particularly on the Democratic Party side of the aisle, risk losing reelection support from the unions’ powerful money machine or a primary fight from a candidate drafted by the Working Families Party.

Working Families Party New York endorses Cynthia Nixon for governor to primary against Andrew Cuomo.

Connecticut’s 2018 election results saw a large swing to the political left. Many blamed the Trump effect, saying the contentious and controversial president energized the left-of-center base in Connecticut. Democrats gained seats in the state House and Senate for the first time in a decade.

The newly formed Progressive Caucus now claims 46 members – including current and former union employees – and the progressives’ stated political goals match the unions’ at both the state and national level.

The Progressive Caucus pushed through a $15 minimum wage and a paid family and medical leave program and continues to push for higher taxes on the wealthy residents of Connecticut.

However, even with a powerful caucus on their side and 14 current or former employees elected to the General Assembly and occupying influential positions in the legislature, not all of the unions’ goals could be reached during the 2019 session.

Some lawmakers, including Gov. Lamont, feared increasing the top tax rate would continue Connecticut’s loss of higher-income individuals and families.

Connecticut is indeed a battleground state for public-sector unions. Their fight now is not with the legislature, but with socioeconomic forces in both the state and the country.

Public-sector unions will not relinquish the battle anytime soon and will continue to pour money into Connecticut’s elections and legislature as they have for years. They will continue to hold tight to the SEBAC agreement for the next eight years, and possibly more depending on negotiations with the governor.

But if the state of Connecticut can’t find a way to fix its finances before the next recession, those union leaders may find themselves waging a war they can’t win and protecting a stronghold state where no one wants to live, work or raise a family.

And that could be bad for everybody, including the unions. There is little use, or money, in guarding something no one wants.

Read Part 1 of this series: Conflict of Interest? Union influence in Connecticut Government.