In 2008, Connecticut took out a $2 billion pension obligation bond in order to boost its teacher pension fund, which the state had underfunded for decades.

The timing was calamitous as the country entered into the Great Recession which saw stock markets and real estate values tank – a period of time from which Connecticut and it’s pension funds that rely on stock market returns — have yet to recover.

The pension bond, however, came with strings attached: the bond covenant required Connecticut to make full payments every year to the Teachers Retirement System and, of course, pay back the bond.

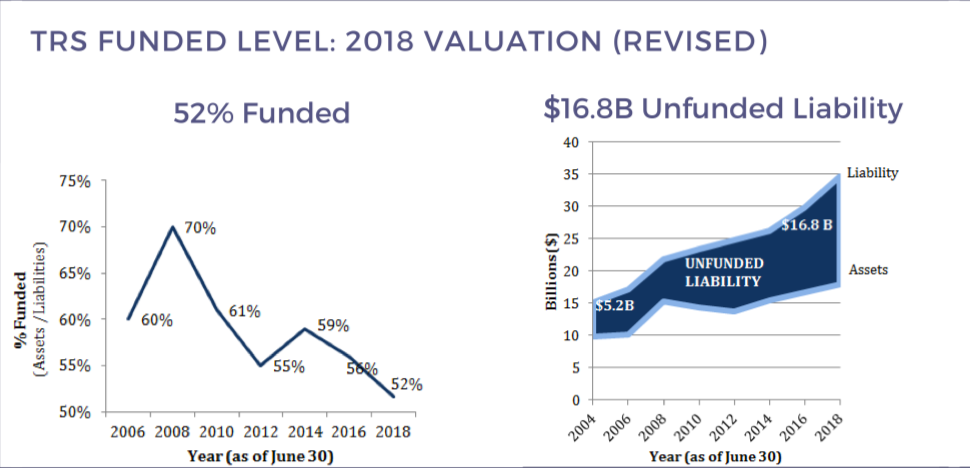

Despite full payments for the last eleven years, funding for Connecticut’s teacher pension system has fallen from 70 percent funded in 2008 when the bond was taken out to 52 percent funded in 2018, according to a fact sheet from the Office of Fiscal Analysis.

According to the OFA, the funding gap has grown from $5.2 billion in 2004 to $16.8 billion in 2018.

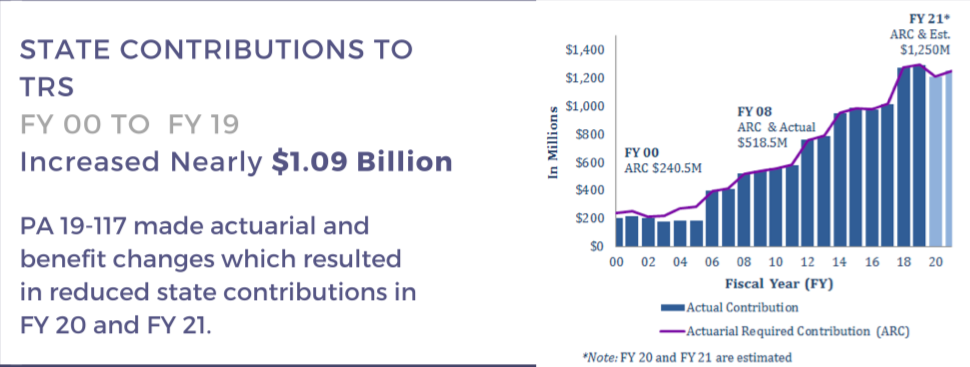

At the same time, Connecticut’s annually required contribution to the fund increased from $518.5 million per year to $1.2 billion during that same time period.

Part of the reason is that the 2008 recession resulted in massive losses for the teacher pension system, which assumed an annual rate of return on market investments of 8 percent.

The assumed rate of return – or “discount rate” – was lowered in 2018 to 6.9 percent to better match actual market returns. The ten-year rate of return was closer to 5 percent and last year’s return was 5.9 percent. Another market recession could put the TRS in an even worse position with negative returns.

The second part of the problem is the ballooning bond repayment.

Connecticut’s pension payments are part of the state’s rising “fixed costs” which include Medicaid, employee retirement benefits and adjudicated claims.

Annual costs for Connecticut’s two major pension funds – the State Employee Retirement System and the Teachers Retirement System – are projected to continue rising, but the teacher pension poses the greater threat.

The Center for Retirement Studies at Boston College issued a warning in their 2016 study, saying if Connecticut continued to not meet rate of return assumptions, the annually required payment could reach $6 billion per year.

The State Treasurer’s Office takes more middle-of-the-road estimate and places the likely growth in payments at more than $3 billion. Either way, Connecticut is looking at a future with unachievable payments and that could ultimately hurt teachers – the very people the pension system is meant to support.

Some remedies have been proposed and have also been met with public and municipal response ranging from lukewarm to near-rage.

The most controversial thus far was a proposal by Gov. Dannel Malloy to move part of the normal cost of teacher pensions – the pension cost minus the unfunded liability cost – onto municipalities. This idea was carried over by Gov. Ned Lamont’s administration.

The latest proposal for a municipal shift by Lamont would have generated $71.5 million in payments by 2021 toward the pension system.

However, the payments made by municipalities would likely just off-set the annual cost for the state, helping to bridge budget gaps rather than contributing more to the pension fund. In the end it would be a wash for TRS.

Municipal organizations and property tax payers who would have to foot the bill balked at the idea, noting it would drive up municipal costs and property taxes while giving municipalities no control over the state pension system – a “you broke it, you fix it,” response.

The legislature also voted to increase teachers’ contribution toward their pension, raising the contribution rate from 6 percent to 7 percent in 2017, raising $35 million.

Unlike state employees whose retirement benefits are set through collective bargaining, teacher retirement benefits are set in statute, meaning they can be changed with a vote – but those votes come at a political cost as teacher unions rallied against the increase.

In the end, it was a wash as the legislature used those increased funds to bridge deficits in the General Fund.

Both the municipal cost sharing and increased contribution from teachers, however, would constitute a small drop in the bucket for Connecticut when faced with the looming possibility of $3 billion per year in pension costs.

The state has also toyed with the idea of dedicating state property and revenue from the CT Lottery Corp. to the teacher pension fund. A state commission was formed to examine the possibility of boosting the teacher pension fund with state property and lottery funds.

Part of that idea found its way into the 2019 budget. The budget created the Connecticut Teachers Retirement Fund Bonds Special Capital Reserve Fund (TRF-SCRF) with a $380.9 million transfer.

The TRF-SCRF will act as a protection for holders of the 2008 pension obligation bonds. Lamont hopes this will enable the state to re-amortize the teacher pension debt to prevent annual costs from spiking without violating the 2008 bond covenant and hurting Connecticut’s credit rating.

If TRF-SCRF funding falls below a set level it will be bolstered with CT Lottery revenue, according to the budget.

Re-amortizing the teacher pension debt will essentially foist more of the debt on future generations but lower payments in the short-term, similar to what Gov. Dannel Malloy did with the State Employee Retirement System in 2017.

The new payment structure will limit the state’s yearly payment to $1.25 billion for 2021, according to OFA.

A 2017 study published by the Yankee Institute offered possible fixes, including moving new teachers onto a defined contribution or hybrid retirement system and allow them to collect social security, which they are currently not allowed to do.

According to the OFA, the average teacher retires after 26 years of service and receives a yearly pension of $60,777 for a normal retirement.

WILLIAM J GREENE

November 14, 2019 @ 12:17 pm

Pushing the unfunded teacher pension liability off to the towns is a bad idea, It merely moves the problem to the towns, it does not solve the problem.

Real long-term solutions need to be implemented:

a.For new hires:

1. switch the plan to a defined contribution plan. Almost all corporations in the private sector have done this over the last 40 years.

b. For existing retired teaches

1. No Change

c. For existing teachers still working:

1. Freeze the pension for teachers with more than 10 years to retirement. All future pension benefits will be in the form of a defined contribution plan.

2. For teachers with less than 10 years to retirement, continue with the same plan but modify it to eliminate the COL annual adjustment.

If you do not take major steps to reform the pension plan, which is only 52% funded, it is like moving the deck chairs on the Titanic. It is not easy, but small steps will not work, and CT will continue with no or shrinking growth.

2.